Furhmann house. 1972. Photograph showing the various stages of construction of the old house on the north side of King Street, East Doncaster. The centre section was built by August Furhmann in about 1858. A skillion of stone was added later, and the front rooms added in the 1880s. The house was demolished in 1976 after the death of August Furhmann's grandson, Hubert (Wiggy) Beavis. Doncaster East; Furhmann, August; King Street; Waldau; Beavis, Hubert DP0231

In 1852 the family settled in Elgar Road. One of the children, William, Beattie's Grandfather, married Margaret Harbour in 1859. She had been the first white child to be born in Doncaster, near the corner of the future Doncaster and Williamsons Roads.

In 1904, Thomas, the father of Beattie, purchased 18 acres at the end of Carbine Street, East Doncaster and planted an orchard. The old house is still standing.

Beavis House, 89 Carbine Street, Doncaster East. Single-storey, double-fronted timber Bungalow. The main value of this site is the landmark of a clump of Pine trees on the rise around the house, now overlooking the recent subdivision, with other pines scattered through the subdivision to the south.

There are a number of other buildings on the property. Two are timber buildings one a small building that could be the original cottage, but with altered windows, and the other a 1930s house. There is also a recent brick house, and a range of outbuildings including a shed and poultry sheds. VHD22475

Beavis Home, 89 Carbine St, East Doncaster Beavis Home Aerial GoogleMaps 2018

George ('Beatty') Beavis's orchard looking towards Church Road, near the corner of present-day Board Street. c1950 DP0445

Apart from the orchard, Thomas used to contract to the Shire of Doncaster for the supply of horses and drays along with their drivers. Both Beattie and his brother Alf used to drive these until their father became a foreman on the council thus making him ineligible as a contractor.

Beattie, whose real name is George, was given the nickname by Mrs Jack Colman when he was a baby and it has stuck with him ever since.

All the family went to the East Doncaster School. Beattie started School in 1918 and left just before his 14th birthday. While at the school one of his teachers was Nell Norman.

Planting the Avenue of Honour, July 1921: Children from East Doncaster Primary School with Mr August Zerbe, planting the Avenue of Honour commemorating the soldiers who died in the 1914-18 War. Zerbe, August; Beavis, Beatty; Burroughs, Doris|; Burroughs, Jack; Burroughs, Ron; Zerbe, Rupert; Crouch, Vic; Crouch, Victor; Daws, Emmy; Forest, Cliff; Sell, Ida. DTHS DP0605

After he left school, Beattie worked for Bob White and Wallie Zerbe on their orchards. He drove for the council for a few years till 1933 then went back to orcharding - working for R.E. Petty until 1941 when he enlisted with the C.M.F.

Australia would not permit conscription at that time so members of the Commonwealth Military Forces were restricted to serving on Australian Territory. After repeated attempts to transfer to the A.I.F., who were volunteers and could therefore serve anywhere, Beattie deserted from the C.M.F. and reported to the Kew Drill Hall. He explained what he had done to Captain Miller who took him to the Royal Park Camp and arranged his transfer to the A.I.F. Beattie was posted to Jahore Bahru in Malaya.

Of the nine children in Beattie's family, six boys and three girls, six of them served in the Armed Services, which is thought to be a record in the municipality. Five of the boys served in the Army and Margaret in the Air force. The family was fortunate, in that, despite the odds, they all survived the war.

When the Japanese overran the Malay Peninsula, the surrender of Singapore was inevitable as the Japanese controlled the water supply which came from the mainland. Beattie's unit was taken prisoner by the Japanese at Singapore on 15 February 1942. It was the beginning of three and a half years of unbelievable suffering and hardship.

The Australians who made up "A" force spent five weeks in Changi Jail before going to Burma as part of the 3000 strong contingent that was to construct the infamous Burma-Thailand railway of death. Beattie's group went to Tavoy in Burma where they worked on the wharfs, then to Ye where they worked on the road to Tavoy. The Japs took everything from the men, the only thing that Beattie saved was his bible, the Japs took it, but after an Australian Officer made representation to the Japanese they returned it, but only after pulling out the maps of the Holy Land. Beattie also managed to hide a small embossed metal dish he had found in the grass at Ye and managed to keep it hidden for the duration of his captivity. Beattie was to spend 25 months in jungle camps working on the railway until it was finished. His last camp was at Tamkan on the River Kwi.

The railway was built without mechanical aids whatsoever, although at one time they had an elephant which the Japs let die through lack of care. All the work was carried out by hand. Cuttings were dug through rock without the use of explosives. The men building embankments and bridges using the strength of their hands, wielding picks and shovels and other hand tools. To drive the piles for the bridges, a solid block of iron weighing two and a half tones was erected on a scaffold and attached to it were four ropes with twelve men on each rope. When all was ready the guard would start chanting. This was the signal for the men on the ropes to start walking, pulling the ropes, thus raising the weight. When the guard stopped chanting, the men let go, the weight dropped, driving the pile into the ground. This continued till the piles were all driven into place. The men worked to a quota of one cubic metre of dirt per man per day, and the quota had to be filled whether the men were fit to work or not. If men dropped out through illness, their mates had to make up their share as well as their own. Work did not stop until the quotas were met, it went on relentlessly regardless of the men's health, weather, disease or any other condition or factor. After all the quotas were filled the men walked back to camp to a meagre meal, and what rest they could get sleeping on bamboo slats.

Due to the need to fill quotas, men who were ill were often asked by their own medics to work. On one occasion, Beattie reported sick but was asked to work. They carried him back with Dengue fever and a temperature of 104 degrees.

Not only were prisoners of war used on the railway, but large numbers of indigenous people were forced to work on the line as well. The number of these who died during the construction will never be known, but it is believed that between 120,000 and 150,000 died, in addition to the deaths of 12,500 Allied Prisoners many of whom died due to the treatment by those responsible for the administration and construction of the railway.

In September 1943, Beattie was sent to a hospital camp suffering from Berri Berri fever and a bad attack of dysentery. At this time his weight was down to 6 stone 13 pounds and he was considered one of the fit ones in the camp. He developed a tropical ulcer on the leg and still bears the scar to this day. The only treatment was to scrape out the ulcer with a spoon, before treatment the patient was given a stick to clamp between his teeth. The patient suffered appalling agony each morning as the ulcers were treated. Beattie also treated his ulcers by standing in the creek which ran past his camp and letting the little fish that lived in it eat away the rotten flesh.

After working on the docks at Singapore, Beattie and his fellow P.O.W.s were taken to Japan. They were then issued with clothing. For two years they had been without boots or clothing, the only thing they had worn was a G string. After living and working in tropical heat, the cold and snow of Japan was another trial to the physically weakened men. At Nagasaki, they worked as coal miners. One day while wheeling dirt out of a tunnel, Beanie saw the plane that dropped the atom bomb fly over. Seven miles away, he saw the flash and the mushroom cloud climb into the sky, but he had no idea what it was.

Beattie's family went through a terrible time while he was a prisoner of war. At first he was reported missing and it was ten months before anyone knew he was alive. In all the time he was away they only received one card from him and he only received two letters. Beattie returned home and went back to the orchard in partnership with Mr. R.E. Petty in Church Road.

Twenty years later problems with surrounding subdivision forced them to give up their orchard so Beattie joined the council Parks and Gardens staff.

In 1948, Beattie and Joan Petty were married and lived in Doncaster Road till 1970 when they moved to their present home in Park Orchards.

Beattie and Joan Beavis joined the Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society during its first year and have been valued members ever since.

Source: 1990 12 DTHS Newsletter from a Monograph by Bruce Bence

The Beavis family were pioneers in the Doncaster area. Thomas and his children arrived in 1849 and joined their uncle Joseph who was living in Stringybark Forest, the area later called Doncaster. One of the boys, William, married Margaret Harbour, the first white child born in the Doncaster district.

Beattie was born in 1913 and five years later went to East Doncaster School. At the age of 14, he left school and went to work on an orchard for a few years, then joined the council staff driving cars and other vehicles.

In 1933, Edwin Petty employed him on his orchard where he met Mr. Petty's attractive daughter Jean.

During the Second World War, Beanie served in Malaya and, when the Japanese invaded, was taken prisoner, suffering great hardship and misery while working on the notorious Burma Railway.

The Japanese sent him to Nagasaki to work on a coal mine where, from only seven miles away, he saw the atom bomb explosion.

After the war, Edwin Petty took Beattie as a partner and in 1948 Beattie and Jean Petty were married.

When the orchard was sold eight years later, Beattie went to work for the Council Parks and Gardens Department for three years.

On leaving the council, he ran his orchard of lemons at Park Orchards and enjoyed looking after and breeding his horses.

In the historical society, Beattie was always a willing worker helping construct the vehicle shed and worked on other projects. He was a member of the committee and vice-president for many years and was a wonderful source of knowledge of the history of the district. Beattie was always generous with his knowledge and, in this, he and Jean worked as a team.

George (Beattie) Beavis will be sadly missed by the Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society. The Society conveys its condolences to Jean Beavis.

Source: Irvine Green writing in 1993 06 DTHS Newsletter

Source: Written by Bruce Bence as told by Beattie (George) Beavis - May 1990. Original Scan: Beattie Beavis Prisoner of War BillLing BruceBence 1990

Australia would not permit conscription at that time so members of the Commonwealth Military Forces were restricted to serving on Australian Territory. After repeated attempts to transfer to the A.I.F., who were volunteers and could therefore serve anywhere, Beattie deserted from the C.M.F. and reported to the Kew Drill Hall. He explained what he had done to Captain Miller who took him to the Royal Park Camp and arranged his transfer to the A.I.F. Beattie was posted to Jahore Bahru in Malaya.

Of the nine children in Beattie's family, six boys and three girls, six of them served in the Armed Services, which is thought to be a record in the municipality. Five of the boys served in the Army and Margaret in the Air force. The family was fortunate, in that, despite the odds, they all survived the war.

When the Japanese overran the Malay Peninsula, the surrender of Singapore was inevitable as the Japanese controlled the water supply which came from the mainland. Beattie's unit was taken prisoner by the Japanese at Singapore on 15 February 1942. It was the beginning of three and a half years of unbelievable suffering and hardship.

The Changi prison, to which Allied POWs were moved in 1944, was intensely overcrowded. Here Australian prisoners are shown 'camped' in the thoroughfare area of the main gaol. Each cell off this thoroughfare housed four prisoners, though built originally to accommodate one. [AWM 043131]

With Commonwealth forces regrouping on the Indian-Burmese border, the Japanese began to build a 250-mile rail link between Thailand and Burma which would enable them to supply their armies by land. It was constructed by thousands of prisoners of war, along with sometimes contracted but usually coerced labourers from Burma, Thailand, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). www.cwgc.org

Due to the need to fill quotas, men who were ill were often asked by their own medics to work. On one occasion, Beattie reported sick but was asked to work. They carried him back with Dengue fever and a temperature of 104 degrees.

Not only were prisoners of war used on the railway, but large numbers of indigenous people were forced to work on the line as well. The number of these who died during the construction will never be known, but it is believed that between 120,000 and 150,000 died, in addition to the deaths of 12,500 Allied Prisoners many of whom died due to the treatment by those responsible for the administration and construction of the railway.

In September 1943, Beattie was sent to a hospital camp suffering from Berri Berri fever and a bad attack of dysentery. At this time his weight was down to 6 stone 13 pounds and he was considered one of the fit ones in the camp. He developed a tropical ulcer on the leg and still bears the scar to this day. The only treatment was to scrape out the ulcer with a spoon, before treatment the patient was given a stick to clamp between his teeth. The patient suffered appalling agony each morning as the ulcers were treated. Beattie also treated his ulcers by standing in the creek which ran past his camp and letting the little fish that lived in it eat away the rotten flesh.

After working on the docks at Singapore, Beattie and his fellow P.O.W.s were taken to Japan. They were then issued with clothing. For two years they had been without boots or clothing, the only thing they had worn was a G string. After living and working in tropical heat, the cold and snow of Japan was another trial to the physically weakened men. At Nagasaki, they worked as coal miners. One day while wheeling dirt out of a tunnel, Beanie saw the plane that dropped the atom bomb fly over. Seven miles away, he saw the flash and the mushroom cloud climb into the sky, but he had no idea what it was.

Beattie's family went through a terrible time while he was a prisoner of war. At first he was reported missing and it was ten months before anyone knew he was alive. In all the time he was away they only received one card from him and he only received two letters. Beattie returned home and went back to the orchard in partnership with Mr. R.E. Petty in Church Road.

Twenty years later problems with surrounding subdivision forced them to give up their orchard so Beattie joined the council Parks and Gardens staff.

In 1948, Beattie and Joan Petty were married and lived in Doncaster Road till 1970 when they moved to their present home in Park Orchards.

George Beattie Beavis working with the Single Furrow Mouldboard Plough

Source: 1990 12 DTHS Newsletter from a Monograph by Bruce Bence

Mr. George Beavis, known to his friends as "Beattie", died during April.

Beattie joined the Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society during its first year and a few years later both he and his wife Jean became life members. They both took an active and valuable part in the life of the group, becoming respected and well-loved members. Beattie restored and donated several items of orchard equipment including spray pumps and the most valued item, the "A" Model Ford Truck.

George Beavis with his plough

Beattie was born in 1913 and five years later went to East Doncaster School. At the age of 14, he left school and went to work on an orchard for a few years, then joined the council staff driving cars and other vehicles.

In 1933, Edwin Petty employed him on his orchard where he met Mr. Petty's attractive daughter Jean.

During the Second World War, Beanie served in Malaya and, when the Japanese invaded, was taken prisoner, suffering great hardship and misery while working on the notorious Burma Railway.

The Japanese sent him to Nagasaki to work on a coal mine where, from only seven miles away, he saw the atom bomb explosion.

After the war, Edwin Petty took Beattie as a partner and in 1948 Beattie and Jean Petty were married.

When the orchard was sold eight years later, Beattie went to work for the Council Parks and Gardens Department for three years.

On leaving the council, he ran his orchard of lemons at Park Orchards and enjoyed looking after and breeding his horses.

In the historical society, Beattie was always a willing worker helping construct the vehicle shed and worked on other projects. He was a member of the committee and vice-president for many years and was a wonderful source of knowledge of the history of the district. Beattie was always generous with his knowledge and, in this, he and Jean worked as a team.

George Beavis and his wife Jean (nee Petty) in Park Orchards

Source: Irvine Green writing in 1993 06 DTHS Newsletter

THE POW's

A special series by Gary Tippett, The Sun 5/10/1984

The day of the deadly cloud!

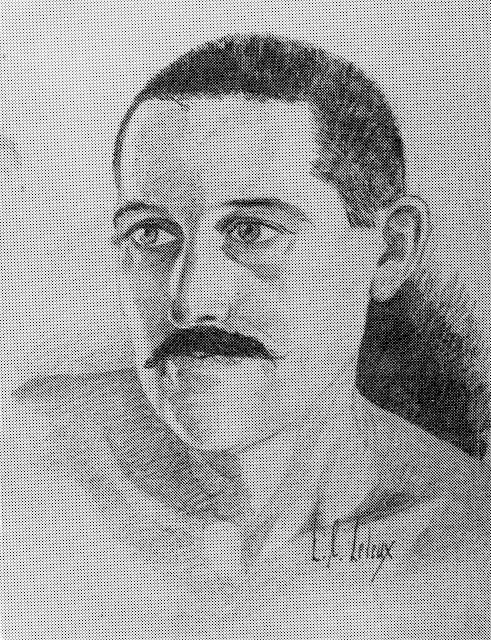

George Beavis on the day he arrived in Japan. His face and body were swollen with beri beri.

George Beavis was wheeling a barrow-load of rocks from a tunnel at a Mitsubishi coal mine at Senju, near Nagasaki, Japan, when he first saw the thing that would become a symbol of dread for every genera- tion to follow.

As the earth shook beneath him, a massive column of black smoke with terrible flames licking through it, boiled thousands of metres into the sky before spreading out in a giant mushroom cloud. It was about 11 a.m. on August 9, 1945, and an American atom bomb whimsically nicknamed "Fat Man" was obliterating Nagasaki and instantly kill- ing more than 35,000 people.

For a moment George, an Australian prisoner of war captured in Singapore three-and-a-half years be- fore, stood awestruck.

"There was no loud explo- sion, in fact I didn't hear a thing," George, 71, now a citrus grower at Park Orchards, recalls. "But I could see the mushroom. I could see the whole lot, just like red hot fire through the air ... and this incredible mushroom.

"In the distance it just looked like a giant electric light pole that went straight up before billowing out. I'd reckon it was about 2000 metres in the air and when it mushroomed out I could see the flare from the fires.

"I'd seen bombs and shells falling in Singapore, but I'd never struck any- thing like that in my life.

"I sang out to the chaps inside the tunnel: 'Good God, come out and have a look, they're going to burn us out!'

"As soon as I yelled out the Japs were running around like mad and hurled us back into the tunnel. The rock inside the tunnel was just shelling off, like a little earthquake.

"I didn't have a clue what it was, but I had seen this mushroom- and I can still see it today."

George Beavis was a pri- vate in the Australian 4th Motor Transport unit when Singapore fell to the Japan- ese in February, 1942. After three months in Changi he was sent with A Force to Burma, where for two years he worked filling in bomb craters at Victoria Pt. aero- drome and on the Burma railway.

There he suffered malaria, dysentry, beri beri and tropical ulcers, reducing him to a 42 kg. walking skeleton. For a while he worked as a hospital orderly, assisting Dr Albert Coates with primitive but life-saving amputations, but mainly he slaved to build the railroad.

In June 1944 he returned to Singapore and on Christmas Eve that year he boarded the Ora Maru bound for Nippon.

"On January 26, 1945, Aust- ralia Day, we arrived in Japan at a place called Moji. When we got off, we went straight into snow- from the tropics all those years, straight into snow!

"Cold, by God it was cold. "We were put into a great wooden building and given a little wooden box filled with frozen cooked rice and a tiny round piece of white radish in the corner, and that was our meal."

The Australians were taken by train to Senju, a small town about 12 km from Naga- saki, where they were to work in the Mitsubishi company's coal mine.

"Before we were allowed down the mine, they'd built a little tunnel sort of thing out of timber in the parade ground. We were given a pick and shovel and our bento lunchbox and we had to start from one end and crawl right along the tunnel carrying all this stuff.

"We were doing this for about 10 days, and we had to learn ‘ogata,' which was an electric motor, 'scoopo' was a shovel and 'hashi,' the beams of the mine. And we had to learn to count in Japanese, like 'ichi, ni, san, shi, go

"I kept thinking to myself 'My God, I'll be glad to get down that mine, it'll be warmer,' and it was.

"The tunnel was barely a metre high at the face, the reef of coal was about 120 metres long, and we moved right up to the electric motor that brought the coal out on an endless chain.

"We quarried it out and each man had to get out five cubic metres a day. There was no gelignite.

"I don't know if the old chap in charge thought I had a bit of nous or not, but he used to keep asking me to go up and work on the electric drill. Though I tried to get out of it, I spent more time right up that end than at the other.

"It was pretty tough. It was a 12-hour shift. You went in at five o'clock in the morning and came out at five in the afternoon and you met the other chaps coming in as you cos were going out.

"We had a big rockfall down there one day that cost me four toenails. There were 14 of us trapped right at the far end and we were there quite a while until they worked up a little escape tunnel and got us out.

"But the same 14 that were trapped there had to go back in through the escape tunnel next day and work from that end while another group worked from the other end to open up the tunnel again.

"That was the worst thing that happened to me there. It was scary, bloody scary."'

The ration on which the 114 prisoners were expected to put in a hard day's mining was meagre, though it was slightly better than what they had grown used to on the railway.

"We had 11 oz. of raw rice a day. When it was cooked it was a good breakfast cup for each meal. Then we got boiled radish, sometimes a cucumber, cooked not raw, and sometimes you'd get a little bit of what they called Chinese cabbage, but not too often.

SOME of the prisoners of war at the camp at Senju, near Nagasaki, at the end of the war. George Beavis is third from the right in the top row.

"Other times we'd get one little backbone of fish, about five inches long by an inch and a half wide, that had been dried. It was just the bone itself, no flesh, and you'd get that for one meal to take down the mine. You could just grab it and chew it.

"But we were better off than the civilian people because they were on only two meals a day. They'd get one lot at 10 a.m. and the other at four in the arvo.

"In the barracks we had no fires, all the cooking was done by steam. We never had any beds, you just lay on straw on the floor and there were about 12 blokes in each hut.

"Conditions were better than on the railway in one sense, but in another sense you couldn't scrounge anything like you could in Burma, where you could find a wild fig or some Chinese mint.

"There was no sewerage, it was all in concrete pits. They had one chap and a woman come in to clean them out daily with a little wooden tub affair with shafts on one end. They had a cow to pull it out and they used to take it out to the vegie growers.

"There was a vegie garden next to the camp and when we first got there, if anyone was caught with his hands in his pockets, they had to go and weed the garden in the snow. You weren't caught a second time. It was snow and slush and it was bloody freezing."

For the most part, the guards were better than the thugs the men had been used to on the railway.

"The men down the mine, some of them were pretty nasty, but the guards them- selves were fairly good, prob- ably because we had quite a lot of older men who had been allies of the British in the 1914-18 war. They were quite a bit more humane than the other crowd.

"But one bloke, Jock MCShane from Glasgow, hao a go at one of the guys down the mine and they made him kneel on a piece of bamboo in the guardhouse for 48 hours. You try it. It must have been shocking

"And we had one chap right down the end of the mine who we called Wart Eye. We hunted and hunted when the war was over to find that bloke, but we couldn't get him. I wasn't going to kill him, none of us would have done that. But we would have made him pay."

On the day the bomb fell, George and several others were working on a tunnel in the side of a hill near the camp.

"We didn't know what it was for, but later we were told it was to put us in to gas us in the case of an invasion by the Americans. After that we were told we would be shot as a reprisal for the bomb."

But at midday on August 16 the men were brought out of the mine and told the war was over.

"The old captain stood up on a table and said: "The order has been given to stop the fight.'

"Some blokes cried and some didn't know what to do. All I can remember is that I sat on the edge of a table with my head in my hands, saying to myself: "Thank God it's over'.'

George stayed at Senju until the end of September before going into Nagasaki. It was here that he finally realised the full force of that mushroom cloud he had been among the first in the world to see.

"You'd have to see it to believe it. Any building that was reinforced with steel was absolutely crumbled and of the buildings just made of bricks, there was just a skeleton of bricks still standing.

"I went into one engineering place and it must have been so hot from the bomb that the bearings and shafts from up above had dropped down and automatically welded to electric motors. It was like arc welding.

"Railway lines were twisted into all shapes, yet the wooden sleepers were just scorched.

"The only people I saw were a few out with little trucks and carts, going through the rubble to see what they could find, but the population was gone, there was nobody. All you could see was the rubble and the outline of empty streets.

"It was cruel to see all that destruction.

"But I'll argue this until I die: I think it had to be. Although it was cruel, it was wicked, I still believe that if hadn't been dropped there'd have been more lives lost.

"Because the Jap wouldn't have surrendered, no way. There'd have been millions more lost by both sides. I think it was those two bombs that made them surrender and ended the war."

Source: Gary Tippett, The Sun 5/10/1984

Original Scan: Beattie Beavis Prisoner of War BillLing BruceBence 1990Beattie Beavis

Beattie drawn by L. Leleux, a fellow prisoner of war

The Beavis family were pioneers in the Doncaster area, the first member of the family to arrive here was Joseph Beavis who sponsored his Uncle Thomas Beavis and his wife Lucy (nee Fitch) and six of their children to come to the Port Phillip District of New South Wales.

The family who came from Coolinge in Suffolk, England, left for Australia on the sailing ship Francis Ridley, which sailed from London on 9 November, 1848 and arrived in Port Phillip on 12 February, 1849.

Thomas was engaged to work for his nephew Joseph whose address was then Stringybark Forest for twelve months on a wage of 25 pounds per annum with rations; their son George was also engaged on a wage of 8 shillings per week and rations, whilst another son William was engaged for three months on a wage of 16 pounds per annum and rations.

Thomas and Lucy Beavis had 11 children, five of whom died before the death of their mother 11 years after the family arrived in Australia.

After their long and perilous journey the family settled in Elgar Road on land brought from Arundle Wright's run in 1852, where they started an orchard after having worked in the timber industry in the Partnership of Beavis and Burt in what is now the Croydon District.

William married Margaret Harbour who was the first child of European parents to be born in Doncaster. Margaret's parents, William and Catherine lived alongside a dirt track near the present day Shoppingtown. The dirt track is now Doncaster Road.

On the 23rd of August, Joseph Beavis, who was a carrier, had a terrifying experience; he was on his way home from Bacchus Marsh with Thomas Drew, they had travelled about 2 miles (3.2 Km) when Joseph stopped to light his pipe, on looking behind him he saw three men coming at them, he and Thomas Drew were attacked and knocked to the ground. It was morning before. Joseph recovered consciousness, only to discover he was covered in blood. On the ground beside him was Thomas Drew also covered in blood and still unconscious.

Joseph aroused Thomas and by slow stages they made their way to the Punt at the Saltwater River (now the Maribyrnong River). By this time Thomas was too weak to travel further on foot and Joseph made arrangements to have him carried to his home in Bulleen by dray.

Thomas Drew died of his injuries early in September and at the time of the inquest, which was held at Heidelberg on the 13 September, Doctor George Butler, who had attended Joseph gave evidence that he had suffered some very dangerous and severe wounds about the head from which he was still not fully recovered.

The inquest into the death of Thomas Drew was conducted in the presence of 12 "good and lawful men of the Colony of Victoria", one of whom was Joseph's Uncle Thomas.

The verdict was wilful murder against some persons unknown. The murderers got 2 hats, a knife, a handkerchief and about 28 shillings for the cost of Thomas Drew's life.

William, the son of Thomas and Lucy, remained on the property after his fathers death, and the other sons moved out of the area, two of the boys - Sam and George moving to Heywood while Tom moved to Lilydale.

William married Margaret (nee Harbour) they had 10 children, 9 sons and 1 daughter, eight of the boys were over six feet tall (183 cm).

The property was sold when William's wife died in 1910, Beattie's father Thomas, bought 18 acres (7.3 Ha), and put in an orchard in 1904, the original home is still standing at the end of Carbine Street, Doncaster East. The family lived and worked on the property until the late 1930s'.

The orchard produced peaches, pears and lemons. The varieties of peaches were selected to provide fruit from December through to February. Thomas would leave for the Market with a horse and a four wheeled wagon at 10 pm and arrive around 1.30 in the morning in time to set up and have a nap before the market opened for the day's trading. When he got a truck he used to leave for the market at 2 am, a long day after picking fruit all day, then grading and packing it before loading up for market. This went on day after day during the fruit season, all the family pitched in to help, each one contributing according to their ability, size and strength.

Apart from running the orchard, Thomas used to contract to the Doncaster Riding of the Shire of Doncaster and Templestowe for the supply of horses and drays along with the drivers as required. Both Beattie and his brother Alf drove them for a time until their father became foreman on the Council, and was no longer eligible to contract to them. Beattie, whose real name George was given his nickname by Mrs Jack Colman when he was a baby and it has stuck with him ever since.

Beattie in uniform before going overseas. He could not have guessed at the terrible ordeal he would go through before returning home. Not only did Beattie survive the months on the railway of death and the years of imprisonment under the Japanese, and all that that meant, not to mention the atom bomb that dropped on Nagasaki where he was working at the time, but he was included in the list of prisoners that were to go to Japan on the Rakuyo Maru. The convoy was attacked by American submarines and the two ships carrying prisoners were sunk. Of the 2,218 prisoners, 1,403 died, of those who survived 159 were rescued by U.S Navy submarines. Beatties' own trip to Japan was made safely, but the ship was sunk shortly after the prisoners disembarked.

All of Thomas and May's children went to the East Doncaster State School. Their daughter Margaret was Dux of the School in her final year. Beattie started school in 1918, in 1919 the school was being remodelled, and for the first two months school was held in the Doncaster Cool Store, the site now occupied by Safeways. Beattie left school just before his

14th birthday and went to work.

Beattie worked for Bob White and Wally Zerbe on their orchards after he left school. In 1933 he finished driving for the Council and went to work for R. E. Petty until 1941, when he joined the C.M.F (Commonwealth Military Forces) as distinct from the A.I.F (Australian Imperial Forces).

The A.I.F were volunteers and could serve anywhere in the world, while the C.M.F was restricted to serving on Australian Territory. Beattie was sent to a Transport Officers School at Sturt Street, South Melbourne, and after repeated attempts to transfer to the A.I.F, deserted from the C.M. F and reported to the Kew Drill Hall where he explained to Captain Miller what he had done. Captain Miller took him out to Royal Park (then a Military Camp) and arranged his transfer to the A. I.F there and then.

Beattie was posted to 4 Reserve Motor Transport Section and went to Jahore Bahru in Malaya.

Of the 9 children in Beattie's family, 6 boys and 3 girls, six of them served in the Armed Services, which is thought to be a record for the Municipality, five of the boys served in the Army and Margaret in the Airforce, the family were fortunate in that, despite the odds, they all survived the war.

Beattie arrived in Malaya in November, 1941, and was in the same unit as Henry Moore from Warrandyte; Henry was a brother of Aggie and Jack Moore.

In Malaya the unit provided transport for a variety of jobs as the need arose, they later moved onto the island of Singapore, where the Japanese kept up continued air raids, usually four a day with some 104 aircraft in each raid. Half the planes would attack shipping facilities and any ships that were about, whilst the other planes attacked targets on the island.

The Allied Airforce were overwhelmed, inadequately equipped as to numbers and woefully outclassed in the performance of the antiquated aircraft they flew, they were shot out of the skies despite the efforts of the pilots.

Singapore was another episode in the continuing saga throughout the early days of the war of "too little too late", as the men and women of the Allied Services paid with their lives and freedom for the neglect of the services by the politicians of the free world during the lead up to the war.

When the Japanese overran the Malay Peninsular, the surrender of Singapore was inevitable as the Japanese controlled the island's water supply which came from the mainland.

Beattie's unit was taken prisoner by the Japanese on 15 February 1942 in Singapore. It was to be the beginning of 3 years of unbelievable suffering and hardship.

The Australians who made up 'A' force spent five weeks in Changi jail on the Island of Singapore before going to Burma as part of the 3000 strong contingent that was to construct the infamous Burma-Thailand railway of death.

The men were crowded into the hold of an old ship Tohoshasi Maru which was like an inferno, as it plodded its way through the tropics.

When the men arrived in Burma they were put to work filling in the huge craters the British had blown in the runways of the Aerodrome at Victoria Point. The men worked in teams of three, one digging out the soil and the other two carrying the dirt in bags with bamboo poles pushed through them for handles.

Victoria Point was the aerodrome from which that great Australian Air Pioneer, Kingsford Smith, took off before he disappeared for ever on his record breaking attempt on the England to Australia air record.

Whilst at Victoria Point the men were given pickhandles to guard the camp against tigers. Fortunately they didn't meet any. While they were there, one of the prisoners escaped, the first one to do so in the area. The Japanese built a barbed wire cage 12 feet square (approx 3.5 metres square) and put the 18 men who had been on guard duty in it without any shelter, They were to stay there until the escapee was recaptured, which fortunately for the guards, happened some five days later.

The captured prisoner was tried and the Japanese Captain stood in front of the prisoners and announced "This man is to be shot". The man was then taken away by the Japanese and executed.

Beattie's group went to Tavoy in Burma where they worked on the wharfs, then went to YE where they worked on the road to Tavoy.

The Japs took everything off the men, the only thing that Beattie saved was his bible, the Japs took it, but after an Australian officer made representation to the Japanese they returned it after tearing out the maps of the Holy Land. Perhaps they thought he was going to escape overland.

Beattie also managed to hide a small embossed metal dish he found in the grass at YE and managed to hide it from the Japs for the duration of his captivity.

Beattie also kept the bible despite the many lucrative offers from men wanting to use the pages for cigarette papers.

At the end of September, 1942, the prisoners were sent from Tavoy to Moulamein by ship where they were housed in the civilian prison for some time, conditions were bad with overcrowding, poor food and sadistic guards, but they were nothing compared to the conditions imposed on them when work started on the railway.

The prisoners were next marched to Thanbuzayat where they started work on the beginning of the infamous Burma-Thailand Railway of death, which was to run some 360 Km (220 miles).

Beattie was to spend the next 25 months in jungle camps working on the railway until it was finished when they met the crews who had started from Bampong in Thailand.

Beattie's last camp was at Tamkan on the River Kwi.

The railway was built without any mechanical aids whatsoever, at one time they had an elephant which the Japanese let die through lack of care. The men worked to a quota of one cubic metre of dirt per man per day, and the quota had to be filled whether the men were fit to work or not, if men dropped out through illness, their mates had to make up their share as well. Work did not stop until the quotas were met. The work went on relentlessly regardless of the men's health, weather, disease or any other conditions or factors. After all the quotas were filled the men walked back to camp to a meagre meal, and what rest they could get sleeping on bamboo slats.

Not only were prisoners of war used on the railway, but large numbers of indigenous people were forced to work on the line as well, the number of these that died during the construction of the railway will never be known, but it is believed that between 120,000 and 150,000 died, in addition to the 12,500 Allied Prisoners of War who died due to the treatment by those responsible for the administration and construction of the railway.

Apart from the quotas the amount of work required often depended on the whim of the guards and the Engineer in charge of construction. The prisoners were given a meal in the morning before they left camp, after reveille which was at 5 am, they took a little box of rice with them for their midday meal and had their evening meal at camp when they got back. Due to the need to fill quotas, men who were ill were often asked by their own medics to go out to work. On one occasion Beattie reported sick, but was asked to go to work, they carried him back with Dengue fever and a temperature of 104 degrees.

While they were at the 14 kilo Camp three men escaped; Bell and Davidson gave up when they realised it was impossible to get away. On their return they were shot by the Japanese. The third man, Captain Mull was shot and wounded by the Burmese Police after he had been out for 28 days, rather than return to the Japanese he took his own life.

All the work on the railway line was carried out by hand. Cuttings were dug through rock without the use of explosives, the men built embankments and bridges using the strength of their hands, wielding picks and shovels and other hand tools. To place the piles for the bridges a solid block of iron weighing 2 tons (2540 Km) was erected on a scaffold and attached to it were four ropes with twelve men on each rope. When all was ready the guard would start chanting. This was the signal for the men on the ropes to start walking with the ropes, thus raising the weight. When the guard stopped chanting the men let go, this continued until the piles were in place.

In September, 1943, Beattie was sent to a hospital camp suffering from Beri Beri, fever and a bad attack of dysentery. At this time his weight was down to 6 stone 13 pounds (44 kg) and he was considered one of the fit ones in the camp.

The hospital wards had no walls only bamboo benches to sleep on and a thatched roof.

While Beattie was there Colonel Albert Coates was carried into the hospital on a stretcher. Colonel Coates was a surgeon and a veteran of the Gallipoli campaign; in two days he took control and cleaned up the camp, in Beattie's words it was "marvelleous".

The

Colonel Coates carried out 120 amputations in 90 days. patients were given a spinal injection that only lasted 7 minutes, most of the amputations were due to tropical ulcers which given proper medication would have healed up.

Beattie developed a tropical ulcer on the leg and still bears the scar to this day. The scar is some 4 inches (10 cm) in diameter. The only treatment available was to scrape out the ulcer with a spoon, before the treatment started the patient was given a stick to clamp between his teeth, he was then held by the arms while the doctor removed the rotted flesh, the patient suffered appalling agony each morning as the ulcers were treated.

Beattie also treated his ulcers by standing in the creek which ran past the camp and letting the little fish that lived in it eat away the rotted flesh.

On another occasion Colonel Coates told Beattie to wrap the leg tightly in a bandage and wet it with his own urine, the bandage was to remain until Colonel Coates saw the leg some days later. Beattie was in agony with it and the stench was terrible, but the treatment did seem to have a healing effect.

When the railway was finished Beattie was to leave Saigon for Japan by sea with a group of P.0.Ws', however the ship didn't sail, as by the time the Allies had control of the seas, so they went to Singapore by train where they worked on the docks loading and unloading ships.

On Christmas Eve 1944 Beattie and his fellow P.0.Ws' were taken to the wharf and put on board the Awa Maru to sail to Japan.

For

The prisoners were issued with clothing when they went to Japan, the clothing was reputed to be made from wood pulp, Beattie reckoned it certainly felt like it to wear them. two years the men had no boots or clothing, the only thing they had to wear was a G String.

After living and working in the tropical heat, the cold and snow of Japan was another trial to the physically weakened men.

Each deck of the Awa Maru had been made into 3 stories, each man was given 4 feet (1.2m) long, 4 feet (1.2m) high by 2 feet (.61m) wide living space, the only time they were allowed out was at meal times (plain rice and not much of it) three times a day. After 31 days the ship docker at Moji on the island of Kyushu.

The prisoners were taken by train to Nagasaki where they worked as coal miners until the war ended, again the work was all carried out by manual labour, no explosives were used, and the quota was five cubic meters per man per day. They started work at 5 am and finished at 5 pm if the quotas had been met. After work they then returned to the camp which was seven miles (11 km) from Nagasaki.

While wheeling dirt out of a tunnel Beattie saw the plane that dropped the Atomic Bomb on Nagasaki; from where they were working only seven miles from the point of explosion, he saw the flash and the mushroom from the blast climb into the sky, but he had no idea what it was.

After they were released and on their way home they travelled through the area, the hills were all blackened and virtually nothing was left of the City.

The Japanese interpreter had told them that they would be buried in the tunnel that they were digging in, in the event that the allies invaded Japan.

Before the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki the Japanese were preparing to gas the prisoners of war at Nagasaki in reprisal for the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

On the 16 August, 1945 the men were brought out of the tunnel and assembled in front of the Japanese Camp Captain. It is not hard to imagine the trepidation felt by the men who had already been told they would be gassed in reprisal for the bombing of Hiroshima, and in the event of an invasion they would be buried in the tunnels, at this unusual happening.

Although the prisoners did not know it Japan had formally surrendered on 14 August two days previously.

The Captain told the prisoners that an order had been given stop the fight"

*to

The end of the war came too late for many of the prisoners who did not survive long enough to see their homes and loved ones again due to the terrible privations that they had suffered at the hands of the Japanese.

Australian Prisoners of War taken at Nagasaki after the war ended. Beattie is third from the right in the back row. The prisoners were photographed in two groups, and the men were arranged so that the best dressed were in front, after one group had been photographed, the clothing was given to the next group.

Beattie's family and friends went through a terrible time whilst he was a prisoner of war, in all that time he only received two letters, both from Jean Petty, the first on 3 September, 1944 wishing him a happy birthday for his birthday in 1943, and another about a month later.

Beattie was listed as missing, believed dead, after the fall of Singapore and it was to be 10 months before anyone knew he was alive. He had arranged for half his pay of 5 shillings per day (50cents) to be paid into the local bank before going overseas. This had been stopped, but was restored to the full amount when it was known he was still alive.

Beattie's family only received one card from him during the time he was away.

This contained about six words and the card

was only allowed to contain certain information.

Beattie's Group of P.0.W's only ever received one parcel in all the time they were prisoners, and it had to be shared between six people, the Japanese had taken out the cigarettes, and the prisoners were only allowed to eat the contents when they were told to do so.

At the end of the war the prisoners in Japan were under American jurisdiction, and American planes came over and dropped supplies in 44 gallon fuel drums by red, white and blue parachutes, the drums were too heavy and they only salvaged about 5% of the items dropped. The prisoners managed to get word back as to what had happened, and a few days later they had a very successful day, this time 50 lb cartons were dropped and they recovered virtually everything that was dropped. Beattie still has a pair of hair clippers the Yanks dropped to them at Nagasaki.

Finally they embarked at Nagasaki for Oakinawa. Just after sailing they ran into a cyclone which they had to ride out for two days, fortunately more comfortable accommodation than on their previous voyages. Several ships went down in the cyclone. When they finally got to Oakinawa a stage had been set up for Gracie Fields to welcome the P.0.W's. Despite the pouring rain Gracie went on with the concert and sang all the popular wartime songs, songs that the P.0.W's had never heard before.

The P.O.Ws' went from Oakinawa to Manila where they underwent medical examinations every other day for 10 days. Whilst in Manila they were issued with complete new kits including rifles and bayonets. One of the characters announced that these people must think we are bloody idiots if they think we're going to lug all this stuff home for them", with than the men promptly dumped everything on the parade ground except the uniforms. Beattie had never seen such a heap of gear in his life.

They left Manila on the British Aircraft Carrier HMS Formidable and 12 days later berthed in Sydney. After another 2 days they were back in Melbourne again, an event that had seemed unlikely to happen on so many occasions since they left so long ago.

Beattie was discharged in January 1946 after being checked for effects of radiation and contamination. He returned for regular checks for a time, but as the results were negative, he gave up going and hasn't had a spell in hospital since he came home.

Beattie returned to the orchard and went into partnership with Mr RE Petty. He commenced building a house which took 27 months to complete, quite good for those times when everything was still in such short supply, Beattie and Jean Petty were married in October 1948.

The partnership lasted until 1965 when the property was sold due to the high rates. Beattie and his wife lived in Doncaster until 1970.

Beattie worked for the Council in the Parks & Gardens Section for 3 years, during this time he planted 4 acres (1.6 Ha) of lemons and built up a Black Poll Stud on their property in Park Orchards, which is now used for agisting horses. Beattie still operates his lemon orchard.

Despite the years that have passed Beattie hasn't had a spell in Hospital since he has been back from the war. Even though he was more fortunate than many of those who endured those terrible years, it took Beattie years to adjust after he came home, and the memories of those years still return.

Beattie is the only survivor of the men who enlisted from the City of Doncaster and Templestowe, and were captured by the Japanese. Three of these did not survive their imprisonment.

The names of those concerned are as follows: Edgar Armstrong; Beattie Beavis; Frank Chivers (died in Burma); Harry Chivers; Wally East (died in Burma); Ned Finn; Earney Fixter; Henry Moore; Bob White; Bill Wood (died in Burma).

We can only wonder at the spirit and fortitude of people that enables them to live through and to survive such a devastating experience.

Before "A" Force left Changi a Furphy got around that the prisoners were going to be exchanged. There was a big four funnelled ship in port that was all painted white and it was going to take them to a Portuguese Island.

When they got to the dock there was no white painted ship in sight, only the disreputable old Tohoshasi Maru. The men were ordered to start loading bags, picks and shovels on board. They soon realised that there was not going to be any exchange of prisoners.

When they reached Victoria Point the men arranged a concert, and Beattie can still recall the words of a poem that one chap wrote for the occasion, they are as follows :

The A Force was thereOn big Changi squareThe furphies as wild as can beFor we left SingaporeAs prisoners of warHoping that soon we'd be free.When we got to the dockWe were due for a shockThere was no neutral vessel to ship onFor the ships on that dayWere all painted greyWith the red and white ensign of Nippon.Our ship Tohoshasi Maru was hardly a flashyWe all began to grumble and mutterWe knew we were soldWhen we were put down the holdIt was like the black hole of CalcuttaThe course that we laidMade exchange hopes all fadeFor we sailed up the west coast of Thailand Disembarked at a jointCalled Victoria PointInstead of a Portuguese Island

Source: As told by Beattie (George) Beavis May 1990.

Jim Beavis working in the Orchard that Beattie and Mr Petty operated in partnership. The orchard was in Church Rd, Doncaster. The photo, which was taken in the mid 1950's is looking west towards Williamson's Rd.

Beattie Beavis photographed about six months after he returned home. The photo was taken at Petty's home in Doncaster Road, Doncaster.

Beattie spraying fruit trees in the last peach orchard in Doncaster Road on the property he worked in partnership with Mr Petty. The orchard was on the corner of Doncaster Road and Church Street. the photo was taken in the mid 60's. The spray unit was later restored for the Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society.

Beattie restoring the orchard spray unit for the Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society, the unit is now in full working condition.

Beattie Beavis restoring a plough for the Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society at his home in Tacoma Street, Park Orchards. Beattie has restored a number of items for the Society including a spring cart, and one of the first A Model Ford trucks. These trucks were bought as engine and chassis, and the local body builder built the body to the customer's requirements.

Beattie and Jean (nee Petty) outside their home, May 1990.

Source: Written by Bruce Bence as told by Beattie (George) Beavis - May 1990. Original Scan: Beattie Beavis Prisoner of War BillLing BruceBence 1990

Addendum - George (Beattie) Beavis

I was interested to read this publication and to note George Beavis had an active involvement with the Historical Society in restoring early orchard equipment at Schramms Cottage.

My brother-in-law Tas Langford, born 28/3/1911 and died 28/4/1977, was a prisoner of war with George Beavis in Changi, on the Burma Railway and finally in Japan. During those years from 1942 to 1945 a very strong bond of friendship, support, dependence and concern for each other was established between George Beavis, Tas Langford, Charlie Everett, Jack Lambell and Ross Smith. This group of 5 shared horrifying experiences including slave labour, starvation, beatings, illness and disease, but were always more concerned about their mates condition that their own.

Their survival was in no small way a result of that close friendship and mutual support. When working on the Burma Railway, George was a great scrounger and would often get a couple of eggs, a chicken or a few pieces of fruit etc from the local villagers, but whatever he got was always shared amongst his mates; especially those who were suffering from illness or disease.

Tas Langford was a great admirer of the courage of George Beavis; the Japanese could never break his spirit, he suffered terrible beatings but would not submit to the brutality and bullying of the sadistic Japanese guards. They all loathed their Japanese captors not so much as for what they did to them individually but for their brutality and beating of others.

After the war the 5 survivors kept in close contact, they met frequently and continued to help each other in settling down to civilian life.

George Beavis was best man at my sister's wedding in September 1947, he had made a remarkable recovery and was a fine looking young man. I attach a photo of the wedding party.

Tas Langford was a diesel mechanic and for many years worked at what was the Tramway bus deport in Doncaster Road. He built one of the first houses on Thompson's Road, Bulleen in the later 1940's. My sister Freda was a great worker at local school canteens especially in the early days of Templestowe High School.

Tas Langford would never own a Japanese car or allow his children to have Japanese toys. He never forgot or forgave their inhumanity to their prisoners especially their brutality to George Bevis.

The amazing medical treatment provided by Colonel Albert Coates (Senior Medical Officer) is acknowledged in the publication. He was a brilliant surgeon and at almost 50

years of age was much older that other P.O.W's. He was a fatherly figure with great concern for his men who years later could readily recall some of his advice and one particular message they could recall was : "Your passport to getting home is in the bottom of your food bowl, eat every last grain of rice no matter how sick you feel."

Also deserving of recognition was Rowley Richards, Regional Medical Officer, only 23 years of age. He had only graduated as a doctor in 1939 but rose to the occasion to serve his fellow P.O.W.'s with compassion, competence and courage. Despite his humanitarian medical role he was frequently brutally beaten by the Japanese for refusing to allow seriously ill men to work. He rightly earned the respect and gratitude of the men he served. Many prisoners owe their survival to such men.

Source: Bill Ling 2007

Original Scan: Beattie Beavis Prisoner of War BillLing BruceBence 1990

No comments:

Post a Comment