The First Electric Road

A history of the Box Hill and Doncaster tramway

To the memory of my grandparents who were all born during the brief existence of the first electric road

Robert Green

An Intriguing Saga in Melbourne's Early History

They said it wouldn't pay for its own axle grease. They threatened it with shotguns and dynamite. They ripped up its tracks and chopped down its power poles. They took it to court. They seized its property and auctioned it off to pay its debts. They compared it unfavourably with a switchback railway and called its directors lunatics. Yet they complained when it didn't run on time.

The history of the first electric tramway in Australia, and the southern hemisphere, is a fascinating glimpse of the conflicts and challenges faced by the promoters of the Box Hill and Doncaster tramline together with the residents, businessmen, politicians, orchardists, passengers, and all the other people who became involved.

The story has been outlined in a brief history marking its fiftieth anniversary, but the full saga has never been told. Now, The First Electric Road’ has been written to present a fully detailed account in commemoration of the centenary year of this pioneer tramway.

Robert Green has been fascinated by trams since his earliest years. He was born in Melbourne, and educated at Caulfield Grammar School and the University of Melbourne. A practising architect, he is a keen historian, particularly of Melbourne’s early tramways, past Chairman of the Tramway Museum Society of Victoria, and former Councillor of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria.

Contents

- Illustrations

- Conversions

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 Sitting over a coil of lightning

- 2 On exhibition

- 3 Forging the road

- 4 The capital,the wisdom and the enterprise

- 5 Up hill and down dale

- 6 The bob-a-week tram service

- 7 Footprints in the sands of time

- Appendices

- References

- Bibliography

- Sources of illustrations

- Index

Illustrations

- Electric railway, Berlin Exhibition, 1879

- ‘Third rail’ system electric railway, Baltimore

- Overhead wire electric railway, Asbury Park

- Lynn and Boston electric railway

- Thomson-Houston advertisement, 1889

- William Masters

- Thomas Draper

- Plan of Centennial International Exhibition

- Centennial International Exhibition, Melbourne

- Thomson-Houston tramcar truck

- Thomson-Houston dynamo

- Ball Engine Company advertisement

- W. H. Masters and Company advertisement

- Centennial Exhibition medal

- William Meader

- Robert Gow

- Doncaster Road looking west from tower

- ‘Doncaster Heights’ auction poster

- Doncaster land sale

- Locality map

- Sectional drawing of tramway

- Box Hill and Doncaster Tramway Company share scrip

- Station Street looking north from Whitehorse Road

- ‘Gem of Box Hill’ auction poster

- Arthur Arnot

- Plant at tramway engine house

- Map of tramways proposed and constructed

- Box Hill terminus on opening day

- Doncaster terminus on opening day

- Cover of banquet menu

- Station Street showing tram shed and engine house

- Handbill advertising tramway

- Intersection of Tram Road and Elgar Road

- Pass issued to Richard Serpell

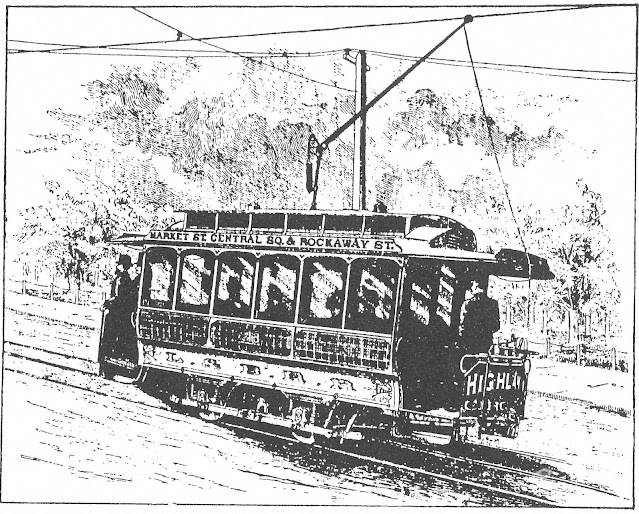

- The original tramcar ‘on the road’

- Map showing Doncaster section of tramway

- The second tram

- Doncaster as seen from Woodhouse Grove

- Richard Serpell

- Alfred Tankard

- View south from near Whittens Lane

- The second tram at Box Hill terminus

- Mathew Glassford

- Doncaster and Box Hill Electric Road Company share scrip

- Henry Hilton

- Day return tram ticket

- Lease between Henry Hilton and tramway company

- William Hilton

- Open tram at Box Hill

- Advertising poster

- October 1893 timetable

- Station Street in 1923

- Site of former engine house, 1933

- Replica tram, Box Hill Jubilee Parade

- Replica tram, Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society

- Henry Hilton and advertising poster in later years

- Commemorative cairn at Box Hill

- Koonung Creek bridge, 1940

Conversions

- 1 mile - 1.61 kilometres

- 1 yard - 0.91 metre

- 1 foot - 0.31 metre

- 1 inch - 2.54 centimetres

- 1 acre - 0.41 hectare

- 1 lb (pound) - 454 grams

- 1 ton - 1.02 tonnes

- 1hp (horsepower) - 0.74 kilowatt

- £1 (pound) - $2 (as at 1966)

- 1s (shilling ) - 10 cents

- 1d (penny) - 0.83 cents

Acknowledgements

Many people and institutions have contributed in various ways to make this work possible. I am indebted to the following organisations for their co-operation and permission to reproduce material from their collections: Public Record Office of Victoria, State Library of Victoria, National Library of Australia, City of Box Hill, City of Doncaster and Templestowe, Box Hill City Historical Society, Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society.

I must also thank the large number of people who have assisted by supplying information, suggestions and clues, and by allowing their material to be reproduced; they include the Serpell family, Mavis Draper, Merrick Hilton, Bill and Mary Hilton, Alan and Harold Williamson, Mary Wallace, Ken Smith, Les Cameron, Peter Duckett, Carmel Moss, Aileen Johnston (nee Serpell), Joan Webster, Keith Atkinson, Billee Henry, Barry Deas, Daryl Bunting, Bob Barnett, Jean and George Beavis, Norm Houghton, Ken McCarthy, Bob Prentice, Keith Kings and Jack Cranston.

I am most grateful to Marjorie Boag who contributed so much to the design and production of the book. Bill Green, Heather Kelly, Geoffrey Boag, Andrew Jeffrey and Sue Chadwick all contributed to its final production. Irvine Green and George Scott provided assistance with the reproduction of photographs and Andrew Nguyen and Vladimir Kapusta prepared the maps. Michael Norbury helped clarify some of the technical intricacies of the story and checked the manuscript. John Keating, Trevor Hart, Jack McLean and Irvine Green also provided valuable criticism of the manuscript. Andrew Lemon graciously provided the Foreword. I sincerely thank them for their contribution and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Norma and Bill Green for their forbearance and support.

Forewood

A road named Tram Road with never a tram in sight, but filled instead with the incessant suburban motor traffic of a metropolis, is about the only visible reminder of a unique past. One hundred years ago this was a country landscape, of rolling hills marked by fences, trees and hedges into paddocks, most of them filled with fruit trees. In spring, when Australia’s first electric tram made its surprising journey through this rural scene, the blossoms were giving way to the fresh leaf. So too, the promoters of the strange new electric traction machine believed, would the horse give way to a fresh form of transport. The tram had the power to transform the city. Could they have even begun to imagine the urban landscape that now adjoins the route of the former Box Hill to Doncaster electric tramway?

It would be easy to grow sentimental about their vanished enterprise. Robert Green in this finely researched study reminds us that the promoters had as their first priority an increase in the value of their considerable land holdings in the district. The project was initiated at the very height of Melbourne’s notorious land boom of the 1880s, and shareholders tumbled over each other like sheep from the pen to take up shares or buy the conveniently subdivided building blocks which were close to the tramway.

The initial success of the tram gave way to a saga of intrigue, dispute, litigation and fraud, leavened only by the enthusiasm and dedication of those who tried to keep the doomed enterprise afloat. It is the same enthusiasm and dedication that Robert Green has brought to this book, which for the first time unravels the tangled facts about a remarkable chapter in the history of our city. It is a keen delight, indeed, to plunge down these hills of the past.

Andrew Lemon, October 1989

Introduction

During the latter half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, street tramways changed the face of cities throughout the world. At their zenith street tramways were perceived as the mark of a city’s progress and success.

The Australian city of Melbourne has always enjoyed the reputation of being one of the foremost tram-cities. At one time it had the largest cable tram network ever constructed; in recent times it has developed probably the largest electric tramway system in the English-speaking world. But in addition to this envied reputation, Melbourne boasts the honour and distinction of having cradled Australia’s first electric tram.

This primitive vehicle first appeared as a working exhibit at the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition in 1888; less than one year after the technology of the overhead-wire electric tramway was perfected in America. Within a further year this little tram was carrying sightseers up and down the hills between the outlying rural townships of Box Hill and Doncaster, 10 miles east of Melbourne. This was the first electric tramway in the southern hemisphere. Here was an example of the latest technology in urban street transport, operating through 2 1/4 miles of virgin countryside, in an antipodean outpost far removed from where it had its origin.

That this tramway should have been constructed in this locality is incongruous, but not entirely surprising. At the time Melbourne was about the thirtieth-largest city in the world and the seventh in the British Empire. The city and its surroundings were booming, and provided fertile ground for entrepreneurs willing to try new innovations.

The promoters of the Box Hill and Doncaster tramway were true pioneers. With sheer determination they made a bold concept into a reality. They were also true ‘landboomers’, all eager participants in the ‘scramble for wealth’ then being waged. In the end the primitive tram, which was underpowered and inappropriate for the job demanded of it, was pushed beyond its limits. After a long series of legal battles and physical disruptions to the line itself, the promoters were left with nothing. Although the line was later resurrected and ran successfully for a short time, the 1890s depression finally precipitated its demise.

In his book Mind the Curve John Keating accurately summed up the Box Hill and Doncaster line when he referred to it as the ‘rather freakish’ electric tramway. It was an oddity; the first and last of its kind. Surely there was no other tramway where the track was physically torn up and the overhead wires torn down over a long-running dispute concerning right of way; and no other tramway operator so beset with litigation. Surely no other tramway could have had such a baptism of fire.

Although the precocious infant did not survive long, it was the first of a family of tramways scattered throughout Australia. Within a decade of the birth of the Box Hill line, all major capital cities except Melbourne and Adelaide installed electric street tramways. Paradoxically these two cities are now the only Australian cities where tramways still operate, although in the case of Adelaide there is but one solitary line.

While vehicles, relics and records relating to the various Australian tramways have been preserved to illustrate the history of a once widespread and important public utility, only a handful of scattered relics of the Box Hill and Doncaster tramway survive. This centenary history has been compiled from written and printed records to compensate in some measure for the absence of more tangible reminders of the first electric road.

Chapter 1: Sitting over a coil of lightning

Electric motors for trams are rapidly coming to the front, and bid fair in the not very distant future to beat all other motors out of the field.

(The President, The Victorian Railways Electrical Society, ‘The electric light in railways’, Building and Engineering Journal of Australia and New Zealand, 11 August 1888, p.88.)

The first street tramway ever built was horse drawn and opened between New York and Harlem in 1832. Although successful, the idea did not immediately catch on, and it was not until the 1850s that horse-operated tramways became widespread. In Australia the eccentric American tramway promoter, George Francis Train, established a horse-operated tramway in Sydney as early as 1861 and at the same time tried unsuccessfully to get a similar line running in Melbourne.

But while horse tramways were an improvement in urban public transport, they had certain drawbacks. Horses had a limited capacity to draw heavy loads up steep gradients and they could only work a small number of hours per day. High operating costs and consequential low profits forced tramway operators to find more cost-effective types of motive power.

Steam-powered trams were an obvious improvement over horse trams, for as long as fuel was applied the steam engine would work non-stop. But steam engines emitted smoke, noise and vibrations. Although steam-powered locomotives were appropriate for railways, which had their own exclusive right of way, they were an unwelcome addition to public streets.

In 1879 Andrew Hallidie perfected a tramway system powered by an underground cable. This was ideally suited to the steep terrain of San Francisco. This method of propulsion could be applied to any tramway, but the high cost of construction put cable tramways beyond the reach of most cities. Although they were quiet, clean and capable of carrying heavy loads, cable tramways had one disadvantage: if the cable was put out of action the whole line was stopped.

While horse, steam and cable power enabled street tramways to operate with some success, the future lay with electric traction. The refinement of electric traction and its application to tramways, as they were known in Britain and Europe, or street railways or street railroads as they were known in America, took place rapidly - within the decade of the 1880s.

Soon after the introduction of the first street railway at New York in 1832, experiments in the use of electricity for motive purposes were carried out around the world. At first batteries were the only source of electricity available, but most inventors soon realised that the small and transient current they produced limited their application for traction on a larger scale. Some, however, persisted with the idea that they were a practical means of propulsion, and during the 1880s and 1890s battery-powered trams ran in a few towns and cities around the world. The main disadvantages of battery-electric propulsion were the heavy weight of the batteries themselves, the offensive fumes they produced and their inability to propel a vehicle over any distance at an acceptable speed. For electricity to be an efficient means of traction, some way had to be found to provide a higher and continuous power supply.

Major developments occurred in 1870 when the Belgian, Gramme, perfected the dynamo, and two years later when he realised that if electricity was applied to a dynamo the machine worked in reverse and produced mechanical energy. Electricity could then be generated by a dynamo and transmitted via electrical conductors to another location, where it could be converted to mechanical energy by means of a second dynamo working in reverse as a motor. This notion created new possibilities for the propulsion of vehicles using electricity.

Until this time railways and tramways had relied upon the primary source of motive power being attached to and moving along with the vehicle. Cable trams were of course different because the cable acted as a medium to convey motion from the stationary power source at a cable-winding engine house to trams scattered remotely along the line. Initially inventors tried using rails to conduct electricity from the stationary power source to vehicles along the line.

Von Siemens, a German, first demonstrated this. Using a Gramme dynamo, he and his partner Halske constructed a small narrow-gauge electric locomotive. This locomotive first appeared at the 1879 Berlin Industrial Exhibition. It ran on a circular track and carried passengers seated on three flat-top trucks which trailed behind. Electricity was supplied to the locomotive via a fixed steel conductor or ‘third rail’ located between the running rails. To complete the circuit back to the generating dynamo, the motor was connected via the wheels to the running rails, which acted as the ‘return’ conductor.

Within a short time Siemens and Halske transformed the principles of their miniature electric railway into a full-size passenger tramway at Lichterfelde near Berlin. They fitted an electric motor to a converted horse tramcar and opened their 2.5 kilometre long, metre-gauge line in 1881. Here Siemens and Halske abandoned the principle of the ‘third rail’ and used each running rail as a separate conductor. While use of running rails and ‘third rails’ as conductors had demonstrated that vehicles could be successfully powered from a remote source, this method had an inherent flaw. Any person or animal which contacted both conductors simultaneously received an electric shock. The line could be fenced to protect man and beast, but this method could never be made to work in public streets. Some alternative method of distribution had to be found if electricity was to be applied to street tramways.

Siemens and Halske soon came up with a new concept which relied on a pair of rigid, slotted conductors (one positive, the other negative) suspended above the ground and running parallel with the track. This was first demonstrated at the 1881 Paris exhibition, where a converted horse tram fitted with an electric motor conveyed visitors from the Place de la Concorde to the Exhibition Pavilion. Power was conveyed to the motor by flexible cables extending up from the car and attaching to shuttles which slid inside the slotted conduits. At last some practical solution to electrical distribution which could be used in public streets had been found. During the next six years Siemens and Halske installed their overhead system in three European cities.

In the British Isles inventors persisted in using the rails as conductors. On the Giant’s Causeway tramway at Portrush, Ireland, a ‘third rail’ was mounted on short posts beside the line and the return circuit was made via the running rails. A steel brush, cantilevered off the side of the vehicle, rubbed along the conductor to make electrical connection. Another interesting Irish line was at Newry, where the ‘third rail’ system was installed in a private right of way.

Where the line road crossed a public road a short length of overhead wire took the place of the ‘third rail’. Power from the overhead wire was transmitted to the vehicle by means of an elementary form of pantograph mounted on the roof. A similar system was adopted at Baltimore, Ohio, by Leo Daft. At road crossings he used a length of rigid gas pipe as the overhead conductor. A pole with steel brush extending up from the roof of the tram made contact with the rigid overhead conductor.

The idea of employing overhead conductors along the whole length of the track was soon taken up by other American inventors including Van Depoele, Short, Henry, Bentley and Knight, and Daft himself. Both single and dual wire systems were developed. In the former the track acted as the negative conductor. With a dual wire system, where one wire was positive and the other negative, power was conveyed to the motor by a flexible cable which extended up from the car and attached to a wheeled ‘trolley’ running along the wires. One of the problems with the trolley system was the tendency for the trolley to become detached and fall from the wires. It also posed design difficulties at intersections and points of divergence.

An alternative type of current collection method that achieved limited success during this developmental period was the underground conduit system. Here a thin contactor or plough attached to the vehicle extended down through a slot in the pavement to make electrical connection with single or dual conductors located in a tunnel under the roadway. In the latter case the running rails were not part of the electrical circuit. The first conduit system was installed at Cleveland, Ohio, by the Bentley-Knight Company in 1884, but it was short lived because a fire destroyed the power plant. Similar systems were built in other American cities and elsewhere but the largest was constructed by Siemens and Halske in 1887 at Budapest, where overhead wires were considered aesthetically unacceptable.

By now it was clear that the overhead wire system was the most promising way to electrify existing tramways and to build new ones. The final breakthrough which led to the superiority of the overhead system came at the beginning of 1888 when the American, Frank J. Sprague, perfected a simple but ingenious method of power collection. Sprague’s system consisted of a rotating grooved wheel on a spring-loaded pole which extended up from the car roof and pressed up against a single overhead wire conductor. The return part of the circuit was formed by the wheels and running rails.

Sprague had devised this idea back in 1882 when he was experimenting with the New York elevated railway, but lack of satisfactory motors at the time caused him to abandon the experiment. Having resurrected the idea, Sprague opened a 6-mile line at Richmond, Virginia, in February 1888. Despite initial technical difficulties with motors and control equipment, Sprague’s system was a triumph. Within a year his line was extended to 12 miles in length and was worked by forty electric cars.

As well as perfecting a simple and effective overhead current collection system, Sprague also devised an improved method of mounting the motors. He was the first man to make the truck (a self-contained frame for the wheels, axles and motors) a separate structure from the car body so that the truck, instead of the car body, took all the stresses developed by the motor. He also supported the motor partly on the axle and partly by springs from the truck frame. This helped to prevent the gears from getting out of mesh.

The evolutionary process of electric traction had reached a climax which enabled practical electric tramways to be constructed. The system which employed a single overhead wire and under-running trolley wheel was superior to other systems on all grounds. It was neat, intersections and turnouts were simply made, and because the wheel and pole were permanently attached to the car, there was no chance of a ‘trolley’ falling from the overhead wire. But above all else, electric traction using the overhead wire system was more economical than any other form of traction.

The flurry to build new electric lines and to electrify lines previously powered by horse or steam began. During 1888 eight electric lines opened in America using the Sprague system. But development of electric street railways was not confined to Sprague. His main competitor was the Thomson-Houston Company established in 1883.

For some years previously Elihu Thomson and Edwin Houston had experimented with dynamos and systems of lighting. During 1888 their company entered the electric railway field by acquiring all the key Bentley-Knight, Van Depoele and Sprague patents. The Thomson-Houston Company, which later merged with the Edison General Electric Company to form the General Electric Company, was in a strong position to exploit the demand for street railways. In 1889 Whipple gave the following description of the progressive and successful Thomson-Houston enterprise:

The Thomson-Houston ‘system’ comprises everything about a street railway that is electrical and mechanical. The Thomson-Houston generator is a powerful machine of low voltage, which occupies small space and is free from many of the objections of the average dynamo. The motor and truck are of special design, and are in practical use on many of the electric roads of the country. For general street car work, one fifteen horsepower motor was used, but on the later roads two of such motors have been placed, one upon each truck [axle?]. The motors are placed under the car floor, out of the way, and are protected from dirt and dust by neat coverings. The ordinary hand brake is attached, so as to be the only apparatus required for starting, stopping, and regulating the speed of the car. Reversing is done by means of a small wrench attached to a bar on either platform. The motors are wound for 220 to 600 volts, depending upon the length of road and number of cars to be run.

The trolley wire, in overhead service, is carried over the center of the track at a distance of seventeen to eighteen feet from the ground, on insulators supported by span wires running across from pole to pole, and provided with additional insulators at their ends, or else by brackets which extend from poles placed on the side of the street.

The whole structure is very light looking, and it seems wonderful that it can be made the medium for the transmission of sufficient electrical power to propel any number of cars over any length of track, as the size of this wire is independent of the number of cars operated or the distance over which the line extends.

The current is taken from the conductor by an ornamental structure on top of the car. This consists of a low skeleton framework, which carries an adjustable, swivelling trunnion having at its upper end a jaw, in which is hinged a counter-balanced trolley pole, having at its extension a grooved wheel, making a running flexible contact on the under side of the working conductor. Owing to the flexibility of this arrangement, it is able to follow with facility variations of the trolley wire two or three feet in either a horizontal or vertical direction, and at different rates of speed or around any curve. The curves are formed of a series of short cords which approximate the central line of curvature.

The Thomson-Houston Company has recently substituted carbon brushes for those of copper previously employed. It is claimed for the new brushes that they have longer life and a much better effect upon the commutator of the motor. (Fred H. Whipple, The electric railway, Detroit, 1889, pp. 140-2. (Republished 1980, Orange Empire Railway Museum)

While the Lynn tramcar trucks were equipped with two 15-horsepower motors, the Thomson-Houston truck under the Melbourne Exhibition tram had one 15-horsepower motor only. Although this was satisfactory for operation under exhibition conditions, when the tram later ran between Box Hill and Doncaster the single motor proved inadequate on the hilly terrain. This contributed to the premature demise of this pioneer line.

As they evolved, electric cars proved their superiority over horse-drawn trams. Referring to the Lynn Road, Whipple said, ‘On the grades which the electric car easily climbs with a full load of passengers, four horses with great difficulty pulled the car with small loads’.(Fred H. Whipple, The electric railway, Detroit, 1889, pp. 128. (Republished 1980, Orange Empire Railway Museum) The new means of locomotion fascinated yet bewildered the travelling public. While some people had the idea that a tramload of passengers was pulled along by the little wheel running along the underside of the trolley wire, others mistakenly supposed that the electricity or ‘coil of lightning’ was stored in a corner under the tramcar seat.

Chapter 2: On Exhibition

The collection of machinery, both silent and in motion, was greater both in extent and importance than any previously brought together in the Southern Hemisphere. (Official Record of the Centennial International Exhibition Melbourne, 1888-1889, The Executive Commissioners, Melbourne, 1890, p.1131)

Of all the Melbourne groups and individuals promoting the use of electricity during the 1880s, the firm of W. H. Masters and Company was probably the most progressive and enterprising. William Masters, a Canadian, migrated to Melbourne in 1870 to introduce a special make of sewing machine.

His partner, Thomas Draper, had arrived from London sixteen years earlier. From an early age Draper conducted many electrical experiments. He illuminated the Melbourne Cricket Ground with arc lights for night football matches in 1879 and together with the Government Astronomer arranged to light the Public Library. Later he installed an imported Edison lighting plant in the Legislative Council Chamber. This was the first incandescent lighting system used in Australia.

Meanwhile the telephone had been perfected and news of this new development spread around the world. Masters and Draper saw a potential market for telephones in the booming Melbourne metropolis and began importing telephone equipment. Masters was familiar with wire communication, as he had worked in a telegraph office as a boy and had erected a telegraph line in Canada. Together with a syndicate of others they formed the Melbourne Telephone Exchange Company, which opened for business in 1880. The venture was an immediate success. A larger replacement exchange was soon built in Melbourne and new exchanges were constructed in the provincial centres of Ballarat and Bendigo. In 1887 the Victorian Government purchased the telephone system for £40,000 and Masters and Draper turned their attention to electricity for lighting and other applications.

By the late 1880s they were agents for many overseas electrical firms and offered their services for practically anything connected with electricity. As agents for the Thomson-Houston International Electric Company, Masters and Draper would have been informed of latest developments in lighting technology as well as the company’s recent involvement in the field of electric traction.

The Grand Avenue of Nations terminated at the middle of the line. Here a broad set of steps led down to ground level, where a ‘station’ was constructed for passengers. From the bottom of the steps a narrow pedestrian bridge spanned the electric railway to give access to a switchback railway along the Carlton Street frontage .

The exhibition, which ran for six months, was opened by the Governor of Victoria in August 1888. During the time it was open more than two million visitors, nearly twice the population of Victoria, attended. More than ten thousand exhibitors from thirty-four countries participated in the event of the decade. In addition to the exhibits there was a wide array of other attractions, including a seal pond, an aquarium, ‘fish river caves’ and orchestral and choral concerts. Sustenance could be had from the temperance and licensed dining rooms, a ‘German Beer Kiosk’ and a ‘Colonial Wine Bar’. A special electric lighting plant enabled the whole place to be illuminated after dark.

Although the exhibition was within walking distance of the city, many visitors arrived by cable tram in Nicholson Street. There was also a temporary service of horse-drawn trams using the completed tracks of the unopened cable line along the north part of Swanston Street as far as Queensberry Street, South Carlton. But while the horse and cable trams were carrying record loads of passengers to the exhibition, Masters and Company were having difficulty in simply getting their newfangled electric tram onto its exhibition track.

Thomson-Houston despatched a tramcar and electrical equipment from its factory in Boston but unfortunately the vessel on which it was shipped encountered bad weather in the Atlantic Ocean. The tramcar, possibly carried as deck cargo, was so badly damaged during a storm that it was off-loaded at London and not sent on. Nothing is known about this tram, but it was probably similar to the enclosed cars supplied by Thomson-Houston for the line at Lynn near Boston.

Although the tram body was discarded in London the electrical equipment, and presumably the truck, escaped damage and eventually arrived in Melbourne. By this time the exhibition was well underway and Masters and Company were anxious to get the tramway running. According to Chauncey Belknap, who later represented Thomson-Houston in Australia, Masters and Company had ‘a car built as expeditiously as possible in Melbourne and the apparatus was put in’.(New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings 1891-92, vol. 5, Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works. Report together with minutes of evidence, appendices and plans relating to the proposed cable tramway from King Street via William Street to Ocean Street, Minutes of Evidence, p.34)

The simple open vehicle had a flat roof, six transverse seats with tip-over backs, a motorman’s platform each end and double running boards each side. With room for six people on each bench, the car had a total seating capacity of thirty-six. The timber-framed body rested on the Thomson-Houston truck, which carried a single 15-horsepower motor.

This motor was typical of the low-powered motors used in the pioneering days of electric traction. In order to make the early motors light, economical and capable of fitting beneath the tram-car, they were run at high speed. It was then necessary to gear down to a lower speed at the car axle. In the case of the exhibition tram, this was achieved with double reduction spur gears having rawhide pinions. In later years as the design of motors evolved, it became possible to make a motor run slow enough for single reduction gearing to be used, thus dispensing with one gear. By the turn of the century 50-horsepower motors were being used.

A prow-shaped timber wheelguard around the truck carried small steel brushes which cleaned the rail ahead of the wheel to improve electrical contact between rail and wheel. Rotating staffs, mounted on each end-platform to the right of the motorman, controlled steel brake shoes fitted to the four wheels outboard of the axles. The roof-mounted current collector comprised a small trolley wheel attached to a 4 feet 6 inch long pivoted mast of four, 3/8 inch diameter iron rods extended apart in the centre. A set of springs attached to the base of the mast kept the trolley wheel at the upper end in constant contact with the wire suspended overhead.

A single rheostat mounted under the car regulated the amount of power supplied to the motor. It operated by means of a leather strap encircling a wooden barrel. A fuse was mounted on the car framing and main switches were provided above the driving positions each end of the car. Eight incandescent lights were provided for night operation, including a bare bulb headlight with simple circular reflector mounted on the end of the roof. Passengers could signal the driver by means of a communication cord running along the centre underside of the roof. This connected to a small bell mounted above the motorman’s head.

The builder of the car body remains a mystery. There is the possibility that it was built by the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company which was then rapidly turning out horse and cable cars at its large carriage works in North Fitzroy. As the exhibition tramcar resembles two open cross-bench cars which operated at Beaumaris, there is also a possibility that it was obtained secondhand from that line. However, a more likely proposition is that it came from the Adelaide tramcar builders Duncan and Fraser. This firm had recently established a Melbourne branch workshop in Alfred Street, Prahran, where presumably it assembled horse trams for the local Coburg, Caulfield and Beaumaris lines.

Before establishing the factory at Prahran, Robert Gow and his brother William were the Melbourne agents for Duncan and Fraser.

In addition Gow was secretary of the Beaumaris Tramway Company and was to become secretary of the Box Hill and Doncaster Tramway Company which ran the tramcar after the exhibition. Reflecting the uncertain direction of electric traction, while arrangements were being made to get the exhibition tram running, Duncan and Fraser provided a double-deck tram and charged the accumulators for a demonstration of the Julien battery-electric system on the then unopened Toorak cable tram track. Duncan and Fraser also exhibited tramcars in both the Victorian and South Australian sections of the Centennial Exhibition.

The belated appearance of the electric tramcar at the exhibition was reported in the Argus on Thursday 15 November 1888. Although several trips had already been made, the tram was not running regularly, as arrangements for admission and registration of passengers were incomplete. The following evening a party of invited guests made a trial trip and next day the tram made more occasional runs when passengers were carried free. After two turnstiles were erected at the ‘station’ the line finally opened for paying passengers on Monday 19 November 1888. The fare charged was threepence per ride.

‘The Thomson-Houston electric tram-car is the first thing of the kind that untravelled Victorians have seen, and the smoothness and noiselessness with which it runs are warmly commended’ wrote one correspondent. (U.S. Senate Executive Documents, 1st Session 51st Congress, 1889-90, vol. 4, Reports of the U.S. Commissioners to the Centennial International Exhibition at Melbourne 1888, Government Printing Office, 1890, ‘Report on the machinery at the exhibition by Andrew Semple of Melbourne’, p.143) He also pointed out that electric tramways were contemplated for Ballarat and other inland cities but there seemed little chance they would displace the admirable cable tram in Melbourne. The Argus took an opposing view, saying the exhibition tramway showed how easy it would be to electrify the cable system by installing wires in the existing underground conduits. It also noted the capital cost savings of electric traction when compared with the cable system. The Age also remarked on the smooth working of the car and the way it ran with ease up the gradient of 1 in 16, even when loaded with over twenty people.

From all accounts the Masters and Company display in the American Machinery Court was one of the largest and most interesting exhibits. It contained a range of dynamos and motors, arc and incandescent lighting, other minor electrical appliances and ‘a large enclosure specially devoted to the display of Electoliers from single to large clusters of lights, and fitted with glass shades in every variety of colour’.(Australasian Ironmonger, Builder, Engineer and Metalworker, 1 January 1889, p22) The display ‘is at night one of the most brilliant places in the exhibition’ wrote the Age. (17 November 1888)

Power for the tramway came from one of the dynamos in the Machinery Court. The overhead trolley wire was apparently divided into insulated sections, to demonstrate on a small scale how power was fed into the trolley wire at each section along the length of a full-size tramway. The Age described this as:

"an arrangement by which the electric current wire can be fed at different points along its course, so that the current need not necessarily be turned on at one end and have to make its way along the whole length of the wire."

Cut-away and exploded view of a Thomson-Houston open-coil dynamo containing spherical armature.

The Thomson-Houston dynamos were of open-coil design with a spherical armature revolving between the poles of two horizontal field magnets. A feature peculiar to these machines was a small air-blowing device which extinguished destructive sparking at the commutator. According to Moir, the dynamo running the exhibition tramway was a ‘400 Incandescence Machine’ which operated at 1,000 r.p.m. and gave an output of 400 volts. (J. K. Moir, Australia's first electric tram, Melbourne, 1940, p.4).

The exhibition dynamos were run by one or two high-speed horizontal steam engines manufactured by the Ball Engine Company of Erie, Pennsylvania. A continuous supply of steam was supplied to exhibitors by the commissioners from noon to 9 p.m each working day. One source states that the Ball engine operating the dynamos was of ‘60 I.H.P.’ (indicated horsepower) and ran at 300 r.p.m. (Australasian Ironmonger, 1 January 1889, p.22)

Moir implies that there were two similar engines at the exhibition and says that the one which later went to Box Hill operated there at 275 r.p.m. and was ‘10 x 12 with overhanging flywheels’. One 4 feet 6 inch diameter flywheel housed the governor. The other flywheel was 5 feet 6 inches in diameter and carried the belt to the dynamo. (J. K. Moir, Australia's first electric tram, Melbourne, 1940, p.4) Contemporary reports of the opening of the Box Hill tramway all state that the engine was rated at 50 horsepower and ran at 300 r.p.m.

Ball engines were distinguished by their unusual governors and valves. The latter gave long and economical service and could be inspected by removal of the steam chest cover while still operating under boiler pressure. Despite these advantages the engines had a small piston clearance at the end of the stroke and due care had to be taken in correctly adjusting the crank and cross head connections. Moir relates that the ‘mate’ of the Box Hill engine disintegrated when later installed for lighting purposes at the Nicholson Street cable tram engine house, possibly on account of incorrect piston clearance.

Well before the tram arrived at the exhibition Masters and Draper formed a syndicate to acquire their Thomson-Houston franchise. In September 1888 the syndicate became registered as the Southern Electric Company Limited Melbourne, with an authorised capital of £ 100,000. Thomas Draper became the company’s managing director.

With the exhibition tram running satisfactorily, the newly formed company was in a better position to promote its potential as a supplier of tramway and lighting equipment. Early in December it invited members of the local Footscray and Coburg councils to inspect the completed display. Although Coburg councillors enthusiastically supported a proposed new electric tramway along Sydney Road, this was not to be. The operator chose horse traction instead, and it was not until the middle of the First World War that the line was finally electrified. Although the company failed to establish an electric tramway at Coburg, it did gain a contract to install electric lighting in the nearby suburb of Essendon.

Despite the late arrival of the tram and the disappointing patronage, the jury adjudicating on electrical apparatus described the Thomson-Houston display as ‘a most complete exhibit’. It said that it deserved ‘great praise for its completeness of system, lighting (arc and incandescent), motors and traction’. (Official Record, p.849) It awarded the display a First Order of Merit and special mention. As a result the Exhibition Commissioners presented the Thomson-Houston Company with a gold medal. The Ball Engine Company was also awarded a First Order of Merit for its high-speed engines.

Unfortunately the tramway was not the success the promoters and exhibition executive had hoped for. The daily average number of passengers was less than three hundred. The Official Record noted that although the tramway was scientifically interesting, patronage had been poor. The tramway closed on 29 January 1889. During the fifty-eight days it operated, 16,928 passengers were carried. The Exhibition Commissioners and Masters and Company each received £105 15s l1d from the sale of rides.

Chapter 3: Forging the road

They cut the route through from Whitehorse Road in the south out across the paddocks, over the Koonung Creek, and up to Doncaster, leaving a brand new road behind them. (Royal Historical Society of Victoria memorandum, quoted in Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board Annual Report 1978-79, p.11)

During the late 1880s there was considerable activity among enterprising electricians who were promoting electricity for new applications. ‘In Melbourne the air is thick with electrical projectors’ claimed the president of the Victorian Railways Electrical Society in 1888. Referring to the development of tramways, he hoped and expected that within a year there would be ‘a tramway or tramways in the neighbourhood of Melbourne worked by electro motors’. (Building and Engineering Journal, 11 August 1888, p.88)

Exactly how far advanced proposals were to construct tramways in the shires of Nunawading and Bulleen when the president made his observations is not known, but he may have been alluding to these early plans when he made this specific reference. The adjoining shires lay about 10 miles east of Melbourne and had the townships of Box Hill and Doncaster as their respective administrative and principal centres. Together these centres were the third-largest fruit-growing areas in Victoria.

The Nunawading shire was described as ‘undulating, picturesque and very healthy’. Box Hill, with a population of 500, was situated on the railway line to Lilydale. It had a bank, two hotels and a brickworks. Box Hill was booming and well serviced. The railway had arrived in 1882 and by 1888 the town had regular letter deliveries and a telegraph service. ‘The property in this district is increasing in value, and buildings are being erected in all directions’ wrote one observer. (Victorian Municipal Directory and Gazetteer for 1889, p.420)

Doncaster, on the other hand, was slightly less fortunate for it did not have a railway. It did, however, have a service of horse-drawn omnibuses plying between Kew Post Office and the Doncaster Hotel, and a daily horse-cab service between Box Hill Station and the Tower Hotel, Doncaster. The latter service was begun in 1887 by William Meader, the proprietor of the hotel. Although it lacked a rail transport facility, Doncaster was still a pleasant place to live and the population of 660 was well served by two schools, two hotels, a post office, two churches and an Athenaeum hall.

The most prominent landmark in the district was the 285 feet high Beaconsfield Tower, standing in Doncaster Road beside the Tower Hotel (near the present-day Tower Street). The Victorian Municipal Directory observed that:

Excursionists and tourists who have visited many places of note in the old countries all agree that the beautiful scenery and extensive field of view to be seen from the Beaconsfield Tower cannot be surpassed. (Victorian Municipal Directory and Gazetteer for 1889, p.275-6)

The earliest evidence of a syndicate planning tramways at Bulleen and Nunawading dates from August 1888, when the ‘provisional directors of the Box Hill, Blackburn and Doncaster Tramway Company’ applied to the Bulleen shire for permission to break up the road and construct what appear to be two separate tramways. The first was to run from ‘a point on the Doncaster Road opposite Mr Clay’s orchard westerly to the intersection of Williamsons Road thence along Williamsons Road to Hanke’s corner’ (Manningham Road), and the second ‘from the Koonung Creek along the Blackburn Road to the section corner at the intersection of Blackburn and Andersons Creek Road being a distance of about 1 1/2 miles’. (Shire of Bulleen minutes, 27 August 1888)

The reasons behind these proposed lines are not clear and they appear to have led from nowhere to nowhere. The name of the proposed company suggests it aimed to build tramways in Box Hill and nearby Blackburn, but there is no evidence that the company applied to the Shire of Nunawading for permission to construct such lines. The first line, about 3/4 mile long, would have commenced near the Tower Hotel and made a wide boomerang-shaped sweep across the west edge of the Doncaster plateau. This line would have passed Richard Serpell’s land at the comer of Doncaster and Williamsons Roads and the second line would have passed William Sell’s property on the east side of Blackburn Road. Both men were probably syndicate members because they were prominent participants in the tramway company that subsequently developed.

The Bulleen Council agreed to give its consent to the proposal when more specific details were submitted. It also requested its secretary to obtain the Governor in Council’s approval to construct tramways within the shire. No mention was made of the type of traction to be used. The council was obviously keen to promote new projects, because only the previous month a deputation of representatives of the Evelyn Tunnel Water Power Company proposed to generate power for transmission to Melbourne via overhead or underground conductors. Although the council agreed to the company laying overhead or underground conductors through the shire from a proposed generator station on the Yarra River, nothing more was mentioned of this scheme. Whether or not this proposal had any connection with the projected tramways is a matter of conjecture. There is the possibility that this scheme could have provided power for the tramway. The precedent of running an electric tram with hydro-electric power had been set five years earlier on the Giant’s Causeway tramway at Portrush, Ireland.

Although the electric power syndicate plans apparently lapsed, there was much activity over the tramway proposal. Within a short time the Blackburn route was abandoned, the Doncaster route was altered, the Box Hill and Doncaster Tramway Company Limited was floated and tenders were called for construction of the line. The prospectus of the new company listed the following thirteen provisional directors:

- J. H. Bussell, 16 Collins St West

- R. G. Cameron, 67 Swanston St

- T. W. Dally, Collingwood

- Joseph Davis, Western Market

- W. Ellingworth, Director Centennial Land Bank

- F. Illingworth, Director Centennial Land Bank

- H. McDowall, Doncaster

- Cr W. Meader, Bulleen Shire

- W. C. Palmer, Queen Street

- Cr W. Sell, Doncaster

- Richard Serpell, Doncaster

- T. Smith, Mayor of South Melbourne

- Cr C. F. Taylor, Selbourne Chambers

The company planned to construct tramways to be drawn by horse or other power ‘for passenger traffic in the Shires of Nunawading and Bulleen, starting from Box Hill railway station along Station Street to a point in Elgar Road Doncaster, 2 miles 68 chains long’. The provisional directors were very keen to get the line operating to capitalise on the approaching holiday season and estimated the cost of constructing the ‘Box Hill section’ and furnishing ‘tramcars, sheds, horses, stables etc’ at £6,500. No specific mention was made of operating the tramway with electricity. (Prospectus of the Box Hill and Doncaster Tramway Company Limited, in K. Smith collection)

The company was officially registered on 24 October 1888, with an authorised capital of £15,000 in £l shares. Its stated aim was to construct and operate a tramway from Box Hill station to the corner of Williamsons Road and Heidelberg Road (now Manningham Road), Doncaster. Such a line would promote sales of land being subdivided north of Whitehorse Road and south of Doncaster Road, would boost tourism and provide Doncaster with a connection to the railway at Box Hill. As no road existed along much of the proposed route, the company had to forge a new one through private property.

Commencing at Box Hill station, the line was to follow Station Street as far as Whitehorse Road. From here it was to proceed along a private road through the properties of C. F. Taylor, the Box Hill Township Estate Company, W. Sell, R. Serpell and W. Meader to the Shire boundary at Koonung Creek. Crossing the creek the line was to zig-zag in a north-westerly direction to the corner of Doncaster and Williamsons Roads, along a road surveyed through the properties of Frederick Illingworth, John Woolcott and others, William Ellingworth and others, a second parcel of Illingworth land then land belonging to Edward Gallus.

Through the first three properties the road was to be named Station Street but through Illingworth’s second property it was to be called Frederick Street, presumably to perpetuate his name. From Doncaster Road the line was to traverse Williamsons Road until its intersection with the present-day Manningham Road.

In addition to constructing and operating the tramway, the company was authorised to supply any form of lighting wherever it wished, and could manufacture and maintain omnibuses. The type of tramcars and method of motive power were at the company’s discretion. The five subscribers to the Memorandum and Articles of Association and the number of shares they pledged to take in the new company were as follows:

- William Meader 500 shares

- Percy J Russell 500 shares

- William Sell 500 shares

- Richard Serpell 1,000 shares

- Charles F.Taylor 1,000 shares

C. F. Taylor, a thirty-nine-year-old barrister, was soon to become Member of the Legislative Assembly for Hawthorn. During the previous year he purchased 345 acres of land on the north side of Whitehorse Road at £150 per acre for residential subdivision. Within days he sold it for £175 per acre to the Box Hill Township Estate Company which he and a syndicate of estate agents, merchants and contractors had just floated for the purpose. With land close to the heart of Box Hill and near the station, Taylor and his partners were destined for success. Percy Russell, a solicitor, had entered into partnership with Taylor’s father. The Hawthorn and Boroondara Standard disparagingly referred to him as Taylor’s aide-de-camp, for Taylor was a captain in the militia.

William Sell owned land in the area and had been elected councillor for the Doncaster riding of the Bulleen shire just the year before. William Meader, a fellow councillor, was president of the Licensed Victuallers’ Association and had just sold the Tower Hotel.

Last but by no means least of the subscribers was Richard Serpell. He settled in Doncaster in the early 1850s and became a pioneer fruit grower. Although he never held civic office, he played a long and distinguished role in the life and development of the locality. He remained a staunch supporter of the tramway through all its vicissitudes.

With the exception of Percy Russell, all subscribers to the Memorandum and Articles of Association became directors of the company. C. R. Staples, a man deeply involved in land speculation and nefarious financial deals, became a director, together with William Ellingworth and Frederick Illingworth. Presumably the latter appointments were made in return for allowing the line to pass through their land. Ellingworth, a Nunawading councillor, also speculated in land and was a director of Illingworth’s infamous Centennial Land Bank. Illingworth bought large areas of land around Doncaster and elsewhere, and in 1889 became Member of the Legislative Council for the Northern Province.

William Meader became company chairman and Robert F. Gow was employed as secretary and manager. Gow was already secretary of the Beaumaris Tramway Company.

Taylor and Russell, Percy Russell’s firm, naturally became the company’s legal advisers. An account was opened with the Doncaster branch of the English Scottish and Australian Chartered Bank and Squire Aspinall and Fred McDonough accepted the role of auditors.

Muntz and Bage (later Muntz, Bage and Muntz), Civil Engineers and Surveyors, were retained to carry out the company’s engineering work. Whether they were paid or given shares in lieu of payment for their services is unknown. By the time the line opened they held 200 shares in the company. Muntz and Bage had considerable municipal consulting experience and were engineers for the Beaumaris, Caulfield and Royal Park horse tramways and the Sorrento steam tramway on the Momington Peninsula.

By the time the line was about to open, fifty-seven individuals held 10,130 shares in the company. Sixty per cent of the shareholders lived outside the area and the local shareholdings were divided approximately equally between the two shires. With 1,500 shares, Frederick Illingworth was by far the largest shareholder; then came Richard Serpell, C. R. Staples and C. F. Taylor (in trust for the Box Hill Township Estate Company) with 1,000 shares each.

Arrangements were made with land owners for the tramway to be laid through their properties, but some were merely verbal agreements and this led to complications later on. The wily Illingworth made sure he would not be caught out; he gave the company a ninety-nine-year lease of a strip of his land abutting Koonung Creek, consideration being that the company would actually ‘make, lay and construct’ the tramway. (Land Titles Office Memorial No. 975, Book 352, Illingworth to the Box Hill and Doncaster Tramway Company Limited, 12 January 1889)

Advertisements for the ‘Doncaster Heights’ subdivision at the north end of the line proudly claimed:

The Box Hill and Doncaster Tram Line will run through this Estate, thus connecting it with and bringing it within 15 minutes of the Box Hill Railway Station. This, together with the duplication of the Box Hill line will bring Doncaster within 40 minutes of the City. (Advertising poster for ‘Doncaster Heights’ subdivision auction, 25 October 1888, Map collection, State Library of Victoria)

| 20-Oct-1888 p.6. The Argus Newspeper. Doncaster Heights No. 2. Clay's Orchard Auctioneer's plans. Batten & Percy (Firm) Publisher: T Smith & Co., Printers: Litho. & General Printers. Elgar Road -- Frederick Street -- Station Street -- Petty Street -- Whittons Road -- Alice Street -- Doncaster Road -- Clay Street -- Arthur Street. Batten & Percy Collection |

Agents and auctioneers for this estate were F. L. Flint, a shareholder in the Box Hill Township Estate Company, and R. G. Cameron, owner of 100 shares in the tramway company. They too had reason to puff up the new enterprise.

For some unknown reason the advertised plan of subdivision for the ‘Doncaster Heights’ estate showed the tramway running north along Frederick Street then bearing north-west through three of the sixty-six allotments being auctioned. Perhaps the agents were so anxious to tell potential purchasers the tramway was coming that it was immaterial exactly where its route lay.

During October 1888 Muntz and Bage called tenders for constuction of the earthworks and permanent way. An offer of £2,900 from John M. Turnbull of South Yarra was accepted for the work, which was expected to be completed early in February 1889. The proposed sections of tramway north of Doncaster Road and south of Whitehorse Road were never constructed.

Arrangements were made for Frank G. Duff of Launceston, Tasmania, to supply some 200 tons of second-hand rails, bolts and fishplates. The first of six deliveries took place on 27 October. The rails cost £5 1Os per ton and the whole order totalled nearly £1,200. The rails weighed 35-40 pounds per yard.

The contractor arrived on site on 7 November and set up camp ‘just the other side of Koonung Creek’. W. J. Moffatt, one of Turn-bull’s men, turned the first sod ‘on the little rise down from Whitehorse Road’ (south of the present-day Thames Street) on Monday 12 November 1888. Some of the occupiers of land through which the line was to pass were jealous of their peace and privacy and many locals were bitterly opposed to its construction. Moffatt later recalled:

As we entered a property the owner was inside with a double barrelled gun to shoot the first man that entered. But the men rushed the fence and the owner walked away so no one was shot.(Box Hill Reporter, 31 January 1941)

As well as contending with the locals, the contractor also had difficulties with his own men. In December work stopped for a few days when the carters called a strike over increasing costs of horse feed .They had been getting 11s per dayand demanded a further 2s. Turnbull agreed to an extra 1s 6d and the men returned to work .

The 2 1/4 mile long tramway between Whitehorse Road and Doncaster Road comprised a single track of 4 feet 8 1/2 inch gauge. It had a maximum grade of 1 in 15.4 (6.5 per cent), an average grade of 1 in 25 (4 per cent) and only 75-100 yards of level track. The section between Koonung Creek and Doncaster Road was particularly steep and included one very sharp 2 chain (132 feet) radius curve. The hilly terrain necessitated some heavy cuttings and embankments and bridges had to be erected over Koonung and Bushy creeks. In March 1889 the Shire of Bulleen received complaints about the dangerous cutting being made by the tramway company at Whittens Lane. A council committee was sent to examine the complaint and the council later agreed to pay half the cost of extra work needed to widen the cutting and reduce the gradient.

The Age fully appreciated the hardships faced by the tramway company, and its determination to apply the new technology of electric traction in an already difficult terrain, when it reported that:

On account of the difficulty in obtaining land along the route, it has not been possible to lay the track in a straight line, so that sharp curves have combined with steep gradients to give the experiment a severe and searching test. (Age, 15 October 1889)

Two different types of construction were employed; about two thirds of the line had the track centred in a 30 feet wide formation with overhead wire supported from rows of poles either side (span wire construction); the remainder comprised a 24 feet wide formation with the track along one side and the overhead wire supported from a single row of poles having cantilevered bracket arms (side pole construction).

The rails were spiked to 4 inch thick blue-gum sleepers 6 feet 6 inches long and 8 inches wide. These were placed about 2 feet 6 inches apart on a 3 inch thick bed of crushed metal. A guard rail was installed on curves as a precaution against derailments. Stone for the ballast was obtained from a quarry beside Station Street near the south bank of Koonung Creek.

The contractor made steady but rather slow progress. By the beginning of March 1889 rails were being laid and by the middle of April the line was almost complete. The Box Hill and Camberwell Express was pleased with the new thoroughfare, claiming that if the job had been left to the council it would not have been built for years. It also predicted the likelihood of increasing property values as a consequence of the road and noted the quality of housing being erected.

Early in February 1889, when construction was well underway, the company requested the municipalities to obtain the Governor in Council’s approval to construct tramways along and across roads under municipal control. Normally a municipality would obtain an order from the Governor in Council to construct tramways within its area, then either build the lines itself or delegate its authority to others.

On 15 February 1889 the Shire of Bulleen advertised its intention of obtaining an Order in Council to permit construction of the line between Koonung Creek and Doncaster Road. The Nunawading shire advertised on 22 March for that part between Box Hill station and Koonung Creek. Despite municipal activity, no Order in Council was necessary to construct the tramway between Whitehorse Road and Doncaster Road because the tramway ran over private land and crossed no government roads. An Order in Council was only necessary when government roads were involved.

However, once started, the bureaucratic process of obtaining an Order in Council continued to roll. In July the Secretary for Railways advised the Roads and Bridges Branch of the Department of Public Works that there was no ‘railway objection’ to construction of the tramway. Four months later, when the tramway was in operation, Muntz, Bage and Muntz were still providing the Department of Public Works with technical particulars of the permanent way and rolling stock. The whole exercise appears to have been futile. There is a lack of any ready evidence that an Order in Council was made.

Although the Bulleen shire gave the question of an Order in Council scant attention, the Shire of Nunawading examined the matter more fully. The Box Hill Township Estate Company was already pressing the Nunawading shire to take over Station Street north of Whitehorse Road and declare it a public highway. So when the question of a tramway along the same thoroughfare (which was still a private street) arose, it discussed the question of road maintenance and arrangements under which it would lease use of the street to the tramway company. Although Moir states that well after the tramway closed Richard Serpell handed over the ‘Delegation Deeds of the road to the Box Hill [Nunawading] Council’, there is no obvious evidence that the council delegated its authority to construct the tramway or was even capable of so doing.

In the tramway company’s first half-yearly report, issued in August 1889, William Meader reported that three-quarters of an acre of ground had been acquired from the Box Hill Township Estate Company ‘at a nominal sum, on a convenient spot at Bushy Creek’, and that the housing for machinery had been constructed. The land, on the south bank of the creek, situated on the east side of Station Street (north of the present-day Wimmera Street), was probably leased from the estate company as the tramway company never became registered on the title as proprietor. The power-generating equipment was installed in a simple corrugated-iron building, which also housed the tramcar. A dam, constructed on Bushy Creek, provided water for the boiler.

Installation of the generating equipment and distribution wiring was carried out by the newly established Union Electric Company of Australia Limited under a £2,350 contract dated 31 May 1889. This company had been formed the previous month by merger of the Southern Electric Company Limited Melbourne (formerly W. H. Masters and Company) and the Electric Light and Power Supply Company of Australia Limited. B. J. Fink, a notorious speculator and land boomer, had a large shareholding in the Union Electric Company and, together with Thomas Draper, became one of its first directors.

In addition to installing the electrical equipment the Union Electric Company was to run the tramway in a satisfactory manner for six months from the date of commencement. Arthur Arnot, a young up and coming electrical engineer and secretary of the Union Company, superintended the contract. Arnot later became the Melbourne City Council’s first electrical engineer.

The power generating plant comprised one of the Ball engines and one of the Thomson-Houston dynamos from the Centennial Exhibition. When the Box Hill tramway opened, the dynamo operated at 1,100 r.p.m. and produced 80 amps at 400 volts. The output was later increased to 500 volts by speeding up the dynamo to 1,200 r.p.m. An under-fired boiler built by Wright and Edwards of South Melbourne provided steam for the engine. The 12 feet long, 3 feet 6 inch diameter boiler had fifty tubes and a 30 feet high iron smoke stack. It operated at a pressure of 100 pounds per square inch. Water from the nearby dam was delivered to the boiler by a Vauxhall pump and Penberthy injector.

Control equipment for the generating plant was simple but effective - a steam pressure gauge, a main knife switch and a number of lamps wired in series which glowed to show that the dynamo was operating. A lightning arrestor was mounted above the switchboard.

The single overhead trolley wire was suspended about 18 feet above the ground. Where the track was centred in the roadway, the wire was supported from cross or span wires attached to timber poles placed about 160 feet apart along each side of the formation. Elsewhere bracket arms cantilevered from poles located along the side of the road supported the trolley wire. The 25 feet long poles were embedded 5 feet into the ground. Many poles carried a sign with the initials of James Barnes, one of the men who erected them. Barnes later became a well known honey producer.

All the overhead electrical equipment was designed and manufactured locally. The egg-shaped insulators, with hooks screwed into each end, were made from the hard and dense wood Lignum Vitae, boiled in oil. A cap fitted to the top provided additional weather protection. The 1 1/4 inch diameter hard-drawn copper trolley wire (No. 4 Birmingham wire gauge), was simply soldered onto the span wires.

In those pioneering days the track, comprising rails simply connected together with fishplates, was inadequate to form a continuous electrical circuit back to the dynamo. To overcome this difficulty a separate ‘ground return’ wire, attached to each rail, ran along the complete length of the track. At Box Hill every rail on the west side of the track was connected with a short wire to a pair of return wires. These were located in some places between the rails and elsewhere outside the track.

Late in September, when the line was almost complete and ready for operation, the tramway company was confronted with the first of a series of legal battles which were to become a characteristic of its brief existence. On 23 September 1889 J. M. Turnbull, the permanent way contractor, issued a Supreme Court writ against the tramway company, claiming £1,538 16s 1d for the balance of his account, the return of his deposit and for extra work done.

The company claimed that the uncompleted work was unsatisfactory and that it had to take possession of the line and complete the work itself. The case was further complicated by the fact that Muntz and Bage had mistakenly issued a final certificate for the work early in May. It is interesting to note that Matthew Glassford, who later held a substantial interest in the second tramway company, was somehow involved at this time and provided an affidavit in support of Turnbull’s case. After many months of disagreement the dispute was settled out of court. It seems likely that Turnbull lost heavily on his contract with the company.

The official opening of the line was scheduled for Monday 14 October 1889. Although the local press reported a successful test of the line on Wednesday 8 October, preparations went wrong the day before the opening when the car apparently derailed nine times. Arnot later recalled spending the rest of the day and much of the night increasing the super-elevation of the curves and greasing the guard rails to avoid mishaps during the opening ceremony.

Chapter 4: The Capital, The Wisdom and the Enterprise

It was a keen delight to plunge down the hills from Doncaster and to speed up the ascents as we sped through the orchards. (Unidentified news cutting in Serpell family papers)

The tramway was to be officially opened by the Victorian Premier, Duncan Gillies, on Monday 14 October 1889. The Box Hill people declared it a ‘red letter’ day and the shire council suspended its usual meeting so that councillors could attend the celebration. A large number of invited guests assembled at the Box Hill terminus about noon and patiently awaited the arrival of the Premier. When it became clear that he would not be coming, the tramway company directors invited Ewen Cameron, the Government Whip, to perform the ceremony. Cameron was the Member of the Legislative Assembly for the electoral district of Evelyn, which included Bulleen. He was also the founding president of the adjoining Shire of Eltham

In an introductory speech the tramway company chairman, William Meader, strongly criticised the locals for their determined and persistent opposition to the tramway. He said that those associated with the company had been considered lunatics for investing in such a venture. He felt sure the opponents would be proven wrong by the success of the line, which was the first electric tramway in the southern hemisphere. He prophesied that within a short time electric lines would be constructed throughout the colony.

In officially opening the line, Ewen Cameron predicted that the tramway would be a great benefit to the district and a boon to visiting tourists. He then severed a cord restraining the car and ‘it glided swiftly away to Doncaster, amidst the vociferous cheers for the success of the company’.(Reporter, 17 October 1889) Two return trips were then made to convey the hundred or so guests to Doncaster, where a celebration banquet costing 10s 6d (half a guinea) per head was held at the Tower Hotel. The hotel was situated on the north side of Doncaster Road about 1/4 mile east of the tram terminus.

The Age reporter enjoyed his outing on the tram and recounted the journey as follows:

The gentlemen who assembled at Box Hill yesterday to try the new means of propulsion had a very pleasant experience, as the trip was of a most enjoyable character. . . When all was ready for a start, the brake was removed and the vehicle glided down the track with a smooth and easy motion. Starting down a considerable slope the pace was allowed to increase after the fashion of the switchback railway until the car was travelling some 12 or 14 miles an hour, and the impetus attained in this way was used in mounting the opposite slope. The pace was slackened considerably in going up the hills, and on the steepest grades only 5 miles an hour was attempted, but still the average speed was good throughout, and the whole distance of 2 1/4 miles was covered in 20 minutes. (Age, 15 October 1889)

Arthur Arnot and the directors were no doubt relieved when all the guests arrived safely at Doncaster. Meader had alluded to the unfinished state of the permanent way during his speech at Box Hill, and Arnot later recalled that on account of the derailments the day before, no risks were taken in transporting the invited guests.

During proceedings the chairman, William Meader, read a telegram from the Premier expressing regret that an afternoon meeting of the Executive Council prevented his attendance. But while the Premier was engrossed in affairs of state, the guests at the Tower Hotel were settling in for a convivial afternoon of oratory.

After loyal toasts to Queen Victoria and the Acting Governor there followed a series of toasts: to the Ministry and Ewen Cameron, the Parliament, the Municipal Corporations, the Tramway Company, the Union Electric Company, the Officers of the Tram Company, the Press and finally ‘The Ladies’. Three parliamentarians and three shire presidents responded to the toasts to the parliament and the municipalities.

Several speakers referred to the long and pressing need for a railway service to Doncaster. Cameron said that locals had been wrong in opposing construction of the tramway on the grounds that it would be an excuse for further postponement of a railway. The guests cheered heartily when he said that he felt satisfied the Doncaster railway would be included in the next Construction Bill. William Meader was not prepared to wait that long. With the troublesome construction of the tramway now over, he buoyantly declared that if the government refused to build the railway he was prepared to float a company and make a start within twenty-four hours.

From all accounts the opening and banquet were successful and enjoyable events. The Box Hill Reporter praised the enterprise in glowing terms and made special mention of the Nunawading shire secretary’s toast to the Press:

His utterances were full of wisdom, and his speech throughout was pregnant with rich thoughts, expressed in choice and elegant language. We do not remember ever having heard the toast of the ‘fourth estate’ being proposed in such a true and effective speech. (Reporter, 17 October 1889)

With the official opening over, the tram began trundling back and forth through the countryside on a regular basis. For the time being opposition to the tramway was overwhelmed by the success of the official opening. The Reporter rode the wave of enthusiasm with the following euphoric editorial: