Needs transcription from Original Scan Images DN2023-05-28B-02

Ghostly memories of the timber cutters

BYWAYS OF LOCAL HISTORY

by Joan Seppings Webster

LONG after the first sawyers and the first settlers of Bulleen and Templestowe lagoon lands had gone to their graves, ghost - like will-o-the-wisps. floated over the marshes.

The light glow bobbing over the low, denuded land was methane gas. Mrs Hazel Poulter remembers being shown it as a child in the early 1920s.

She tells us that wild flowers which abounded in Templestowe then can still be found growing in Warrandyte. There was a pink flower, called Century, used by early settlers to make a medicinal herb tea and this, she says, still grows near her home.

Deadly Nightshade is still there, too, another rather morbid, lingering relic of bushland days.

Under the surface of the ground was a fungus, which was called "blackfellows bread." "It looked like cooked sago when opened," said Mrs Poulter. This was often unearthing, when ploughing.

Stone axes and stones from an Aboriginal burial ground were also ploughed up.

But before ploughing was possible, trees had to be cleared.

Mrs Poulter's father, Harold Morrison, was a master plumber by trade and developed his Templestowe orchard in his spare time, at weekends.

"Trees would be pulled down with a trawalla and cut into lengths. The trawalla was a large ratchet-type jack. A cable would be attached high up on the tree and the trawalla anchored at the base of another tree.

The ratchet would be worked with a lever to pull the tree over. Very large trees would be felled with a cross cut saw, and one such tree nearly hit our house," she said.

Mrs Morrison was typical of wives who during the week when their men were working at other jobs, or taking wood to market, kept fires going, burning out the tree stumps.

Bark was stripped from wattle trees and taken by horse and wagon to a tannery at Preston.

Usually one acre was cleared at a time.

Then a local man with a special plough would be employed to break up the virgin soil.

A canoe tree. from which Aboriginals had carved at bark canoe, was on the Morrison's land. Footholds cut by stone axes into the trees were visible.

When the soil was broken stones were dug out and carted to the nearest headland of the river.

Wearing a bag Morrison moved stones away.

Newman's Role of those surfaced broken stones from cleared land.

This was the way was developed, the same in Doncaster in Park Orchard burning, rooting planting. Cutting trees to grow plants, then planted trees as well, help the young survive in the bare soil.

Using local roads, drains and cycle of destroy accomplished by neighbour helping.

171 ByWays DoncasterMirror

22 March, 1985

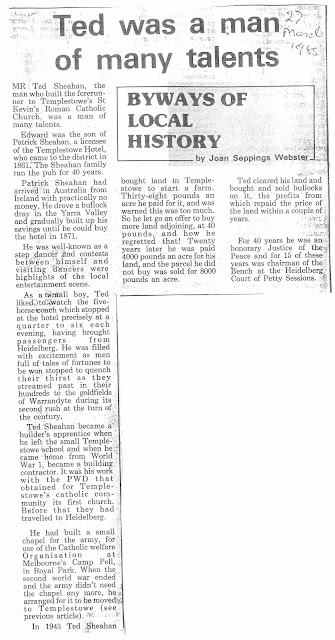

Ted was a man of many talents

BYWAYS OF LOCAL HISTORY

by Joan Seppings Webster

MR Ted Sheahan, the man who built the forerunner to Templestowe's St Kevin's Roman Catholic Church, was a man of many talents.

Edward was the son of Patrick Sheahan, a licensee of the Templestowe Hotel, who came to the district in 1861. The Sheahan family ran the pub for 40 years.

Patrick Sheahan had arrived in Australia from Ireland with practically no money. He drove a bullock dray in the Yarra Valley and gradually built up his savings until he could buy the hotel in 1871.

He was well-known as a step dancer and contests between himself and visiting dancers were highlights of the local entertainment scene.

As a small boy, Ted liked to watch the five-horse coach which stopped at the hotel precisely at a quarter to six each evening, having brought passengers from Heidelberg.

He was filled with excitement as men full of tales of fortunes to be won stopped to quench their thirst as they streamed past in their hundreds to the goldfields of Warrandyte during its second rush at the turn of the century.

Ted Sheahan became a builder's apprentice when he left the small Templestowe school and when he came home from World War I, became a building contractor.

It was his work with the PWD that obtained for Templestowe's catholic community its first church. Before that they had travelled to Heidelberg.

He had built a small chapel for the army, for use of the Catholic welfare Organisation at Melbourne's Camp Pell, in Royal Park. When the second world war ended and the army didn't need the chapel any more, he arranged for it to be moved to Templestowe (see previous article).

In 1943 Ted Sheahan bought land in Templestowe to start a farm. Thirty-eight pounds an acre he paid for it, and was warned this was too much.

So he let go an offer to buy more land adjoining, at 40 pounds, and how he regretted that! Twenty years later he was paid 4000 pounds an acre for his land, and the parcel he did not buy was sold for 8000 pounds an acre.

Ted cleared his land and bought and sold bullocks on it, the profits from which repaid the price of the land within a couple of years.

For 40 years he was an honorary Justice of the Peace and for 15 of these years was chairman of the Bench at the Heidelberg Court of Petty Sessions.

172 ByWays DoncasterMirror

17/4/85

From Cornwall to the highlands of Doncaster

BYWAYS OF LOCAL HISTORY

by Joan Seppings Webster

ATOP a hill to the south of Reynolds Rd and west of Blackburn Rd is a fine old brick homestead. Once, it was monarch of all it surveyed, and from the home that was his castle, Richard Serpell could see his own land stretching both sides of Blackburn Rd down to Serpells Rd and enjoy a panoramic mountain view. Only a few years ago, this home could hardly be seen for its surrounding orchard. Now it is exposed.

In place of rows of fruit trees are rows of new houses, bare as yet of gardens, as once Richard Serpell had bared the original bush surrounding it. The Serpell home, also known as the Jenkins Homestead, is now Hemingway Av. near Jenkins Drive. Richard Serpell's mother Jane brought her Cornish family of a daughter and four sons to Glenferrie, where they had a store.

In May, 1853, they bought their first Doncaster land at the corner of King St. and the level of what is now Tuckers Rd. From Glenferrie they often walked to their land "in the highlands", as was written in the diary, to plant fruit trees. From the Serpell diary: June 28, 1854, — "Visited the highlands, mother, Dick and I, taking some fruit trees and other things with us." Aug. 29 — "Digging ground, planting currants, gooseberries, vines and a few fruit trees."

By 1855 they had built a two-roomed bark hut. 1855. Aug. 18 — "The boys and mother came up with the dray bringing a number of fruit trees." 1856. July — "Large piece of land planted. 108 trees of various kinds. 112 vines. 56 currant bushes and 66 gooseberries." 1858. Jan. — "I rode as far as the White Horse and walked to the farm and found all well."

Two men, Arthur Liddelow and one called Harry, were employed: A bushfire menaced. "Mother, Aunt, Henry, Dick fought it as it threatened our house." By 1860 "peaches and fruit trees bearing well". The family bought up more land. In 1875 Richard married Annie Beeston and built his home, the homestead in Hemingway Av. He quarried clay on site and baked it into bricks on the spot in a portable kiln and built four rooms.

Annie died in childbirth, their first. The baby was named Annie after her mother. The motherless babe was reared by her grandmother and was to become Annie Goodson. wife of a schoolteacher, whose own home was atop the most magnificent hilltop of all. Doncaster Hill. It was demolished a few years ago to make way for extension to the car park for Doncaster Shoppingtown.

In 1879, Richard married again — Alice Reid, from Phillip Island, but lived for only a short while on the Blackburn Rd property. A tragic drowning in the orchard dam brought with it the feeling that this was an unlucky home, and Richard built again near his mother and little Annie, on the eastern side of William-sons Rd, just north of the Doncaster Rd intersection.

Richard Serpell was a member of the company formed to run the first electric tram in the Southern Hemisphere (along Tram Rd. from Box Hill to the top of the hill); helped established the Athenaeum Hall and its once famous library: donated land for the Doncaster Primary School and old Shire Hall; carted stone to help build Holy Trinity Church of England and built the store on the corner of Doncaster and Williamsons Rd (White's corner) demolished for Doncaster Shoppingtown.

October 23, 1985

Extractive industry of our early days

BYWAYS OF LOCAL HISTORY

by JOAN SEPPINGS WEBSTER

Henry Zelius, brilliant brother, loved in Dancaster Rd. In a home seminar to Plassey.

MANY a tooth was pulled out in the parlor of the quaint old house with the double ridge roof and palm trees on the west side of Leeds St, just south of Renshaw St.

Built in 1860 as the home of lemon orcharding pioneer William Sydney Williams and his wife Anne, it later became the home of their twelfth child, Alice, who was born there in 1878.

Alice's husband was Henry Zelius, a dentist, who had grown up in what was known as the most elegant house in Doncaster, "Plassey", the white house on the corner of Doncaster Rd and Denhert St,

opposite where Woolworths now stands, which was built by his father, Martin, a shipping trader.

No injections of anaesthetics were given for tooth pulling in those days. In fact, many people had no dentist. In 1900, Australia had only 738 dentists.

The Victorian Dental Act had been passed in 1888 (the year Henry's father built "Plassey"), but the training of dentists by indenture began only in 1897, so the traditional tooth-pullers for a long time were blacksmiths, who had strong tongs, or the barber, doubling as surgeon.

Young dentists such as Zelius worked as apprentices for three years at a shilling a week, paid to the master. The new brass plate could show "Occulist, dentist, corn operator. Teeth extracted, cupping, bleeding, horse and cattle medicines" and "Loose teeth fastened".

Poppy juice

Although the first subcutaneous injection to deaden the pain of dentistry was given in England in 1845, a century later many Australian teeth were still being drilled without that benefit.

Very old analgesics were mandrax root, poppy juice or alcohol.

The foot-operated drill was invented in 1874, but only a few leading dentists were using them.

Around Zelius's time, some dentists were still using a mixture of silver and mercury for fillings, but this, being poisonous, was frowned upon by up-to-date dentists.

The others probably found it easier to mix and press into the cavity than the old-fashioned ground animals' teeth, or a piece of walrus bone screwed or hammered into place and fastened with slaked lime and turpentine or strong fish glue.

"Natural" false teeth were made from human teeth, alive or dead, sold by the poor or obtained from body-snatchers, and mounted on ivory or gold. Of lesser cosmetic effect were those carved from bone or ivory.

By 1900 some leading dentists were using dental nurses, but Henry Zelius, like most, called on Alice if he needed a helping hand.

To us, dentistry of his day may seem primitive, but he had come a long way since tooth-pulling was a street sideshow in the 1880s, and "Painless Teeth Extraction" meant that a band played so that the patient's yells were drowned, while the operator held the tooth aloft to the watching crowd.

175 ByWays DoncasterMirror

20/11/85

Of tragedies and triumph

BYWAYS OF LOCAL HISTORY

by Joan Seppings Webster

BABIES died, new families were started; life partners died, new partners found; new lives started; stability found, heritages begun.

This was the story of so many Australian pioneer families, coming as they did to unused climates, unsuited to clothing and cultures; living as they did in an age before infection and its spread were understood, before nutrition and its needs were cared about.

Many coming from crowded industrial revolution slums to wide country spaces; others from fresh village life to new city slums. In the following sections, we will discuss the ways of our citizens and triumph that are committed to their journey.

The first thing is that of Johann Gottfried. We have been the son of Samuel Uebergang, on September 9, 1821, at Profen, Silesia, Prussia.

On May 17, 1853, the year so many of our city's first migrants left their home country, Johann Gottfried, his wife Charlotte and their three young children, Gottfried Heinrich, Johannes Caroline and Ernst, with his brother, Carl, and sister Anna and their families, left for Australia.

On the voyage, little Ernst died. The ship Wilhelmsburg landed the rest of the family at Melbourne on August 25.

Their first home was in what is now known as Victoria St., Collingwood (then Simpsons Rd.), There, five-year-old Gottfried Heinrich died, and the small coffin was buried in the old Melbourne cemetery, over which Victoria Market later grew.

At the end of that year of changes, Gottfried, Charlotte and Johannes Caroline came to Doncaster's German community and lived in Germany. German Lane (now George St.).

The new move seemed to promise new hope and joy for the future when early in the new year, on January 14, 1854, the first Uebergang child to be Australian born arrived, Carl Heinrich Gustav.

But just one year later, when Gottfried was away from home and now understood to have been at the goldfields with his Doncaster friend, Carl Aumann, trying his luck to better his family's situation, Charlotte died.

Gottfried was left with the toddler John Caroline and the old baby. Good friends were all he had. In 1859 he left the children with friends and returned to his home town in Silesia. A wife with his own background was what he needed.

He married Christianna Konig and brought his new wife back to the children in Doncaster at the end of that year, just six years after his first migration.

As the next new year began, he took his new country completely to heart, became naturalised, bought 20 acres of land in Wilhelm St. (King St.), built a wattle and daub hut and later, on land which he turned into a successful orchard, a substantial home which stood for 100 years.

Gottfried and Christianna had two sons and a daughter. The boys, Henry and Charles, established orcharding families here.

July 23, 1986

Byways of Local History

by Joan Seppings Webster

MUCH of Doncaster's previous orchard scenery was typified by the pine trees introduced by the European settlers as windbreaks.

But a rarer pine, still to be seen in a few places, is indigenous to Australia. It is the beautiful Bunya Bunya, often called the Monkey Puzzle Tree (Araucaria).

It is a cone-shaped tree with spaced, drooping branches which let the light through and grows to about 60 metres high.

One can be seen on Doncaster Rd., in the grounds of the golf links, close to the road and not far from the shed which was once the stables of Dr. Thomas Fitzgerald's magnificent residence.

These Bunyas were introduced to Doncaster by Baron von Mueller, who helped design Melbourne's Botanic Gardens.

They are a reminder that Australia's countryside was not always dominated by eucalypts and wattles.

Up until 20 million years ago - southern and central Australia was covered with rainforest. The climate has swung from moist to dry, warm to icy and with these changes the vegetation altered.

At times over the past 700,000 years, the south- east of Australia has been covered with alpine herbfields and grasslands and at others a mixture of temperate rainforest and she-oaks (Casuarinas).

Drier times and their increased bushfires all but wiped out these fire-sensitive trees, even in the north-east of Australia.

It was there that the pines, among them Bunya Bunya, dominate and after rainforests.

This description of Queensland's Bunya Mountains, where it used to abandon, was written earlier this century by Marianne North in her Recollections of a Happy Life:

"I rode ... through the grand forest alone ... and reached the magnificent old Araucarias. Their trunks were perfectly round with purple rims all the way up - straight as arrows to the leaf tops which were round like the top of an egg or dome and often 200 feet above the ground.

"These grand green domes covered one hundred miles of hill tops and towered over all the other trees of these forests.

"Nowhere else were the old Bunya trees to be seen at all; and at the season when the cones ripened the native population collected from all parts and lived on the nuts, which were as large as chestnuts.

"Every tree was said to belong to some particular family and they produced so great an abundance of fruit that it was also said the owners let them out to other tribes on condition that they did not touch the lizards,

snakes and possums - a queer form of game-preserving which reduced the hires to such a state of longing for animal food that babies disappeared, and then there was a row, and no white person ever ventured on these hills while the bunya harvest was going on."

The beautiful pale timber of the Bunya was found by the European settlers to be very suitable for the furniture and so it is not surprising that Marianne North wrote further in her story:

"Great piles of saw-dust and chips, with some huge logs, told that the work of destruction had begun and civilised men would soon drive out not only the aborigines but their food and shelter."

Doncaster's rare specimens are worth preserving and propagating. A most beautiful example once grew in front of the municipal offices but was cut down in the early 1970s when the road was widened.

THE timber cutters of early Doncaster played an unwitting role in a colonial bureaucratic intrigue to destroy what was then one of Melbourne's most renowned and beautiful structures - Princes Bridge.

The first means of crossing the Yarra from north to south Melbourne was by means of hiring private boats or paying a puntman.

The first bridge was of timber - built in 1845 - and crossed the river in a slanting direction a little up-stream from the present bridge.

Superintendent La Trobe had wanted the bridge to be located at Elizabeth St., but as several water was never metres deep, with the bed thick mud, the construction company favored Swanston St., where the water was only two metres deep and with a hard, gravelly bed.

The bridge was privately leased and a toll charged for crossing it.

In 1850 this was replaced by Melbourne's pride - a single, elliptical span arch of 50 metres of granite and bluestones with its crown only 10 metres above the water of "very light, graceful and artistic appearance".

The arch was the flattest ever thrown, being one-fifth of its height and flatter than the famous bridge at Neuilly, France.

It was not only the longest span in the colony but the second largest of Europe, being only two feet shorter than the main arch of London Bridge. What is more this Princess Bridge was free to cross.

This was only 14 years after the first settlement of Melbourne and as time went on and the population grew the Yarra's natural but inconvenient tendency to flood and carry away haystacks and cottages filled the miners in the politicians and engineers.

They decided that the river must be improved by widening it six times, deepening it and removing from it a barrier of reef that formed a waterfall.

Part of these plans included a new bridge.

The reef, not far from the bridge and known as the Falls, was stated by Aboriginals to have been formed during an ancient earthquake which formed the harbor and shifted the mouth of the Yarra from Cape Schank to a delta near Fishermen's Bend.

The boulders of the Yarra Falls reef were believed by some early settlers to be the edge of an extinct volcano.

One of the chief obstacles to constructing a new Princess Bridge was that the old one was so beautiful.

So the Public Works Department resorted to what its Minister, Mr Deakin, described as "an innocent piece of strategy".

In 1883 he introduced a Bill to authorise the contemporary of a temporary bridge in place of the old bridge because, as said, it was felt that as long as the old bridge stood before the eyes and in the hearts of the people of Melbourne there would be no chance of getting a new bridge.

The old bridge was pulled down and the replacement was deliberately contrived to be "such a structure as would not satisfy the people for any period of time".

It seems a curious plot and a waste of public money but that, according to Garryowen, is the way Melbourne got its present Princess Bridge - then acclaimed as the widest in the world - opened in 1886.

The timber cutters of early Doncaster provided timber for the temporary bridge, at the time also graced by the name of Princess Bridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment