Modern Refrigeration:

The Vapour Compression Cycle main components are:

Source: Refrigeration Cycle! animation Jan2025

The internal workings of the cooler's expansion valve.

Source: What's inside a Thermal Expansion Valve TXV - how it works hvac Jan2025

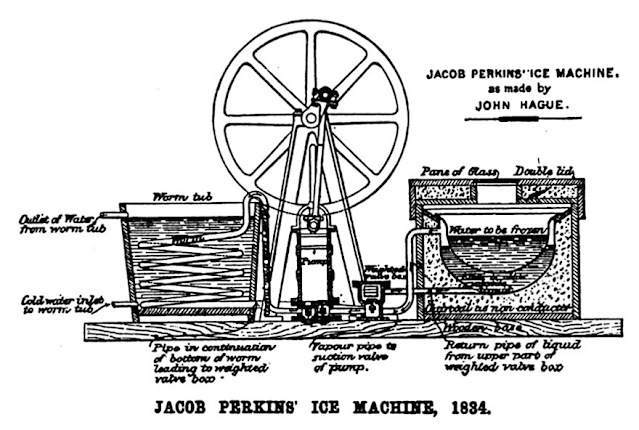

Jacob Perkins

Jacob Perkins, was an inventor in many important areas. Perkins is credited with the first patent for the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle, assigned on August 14, 1834.

James Harrison

James Harrison, born in Scotland in 1816, was a newspaper owner, among other things.

While the owner of The Geelong Advertiser, he became interested in refrigeration and ice-making after observing that while cleaning movable type with ether, the evaporating fluid would leave the metal type cold to the touch.

Ice-making operation and later life

Harrison's first mechanical ice-making machine began operation in 1851on the banks of the Barwon River at Rocky Point in Geelong.

Because of the cost of importing ice from the United States and Norway for use in ice houses,

Harrison's device became a financially viable alternative for the remote Victoria colony, and his first commercial ice-making machine followed in 1854, along with a patent for an ether refrigeration system granted in 1855. This novel system used a compressor to force the refrigeration gas to pass through a condenser, where it cooled down and liquefied. The liquefied gas then circulated through the refrigeration coils and vaporised again, cooling down the surrounding system.

The machine employed a 5 m (16 ft.) flywheel and produced 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb) of ice per day. In 1856 Harrison went to London where he patented both his process (747 of 1856) and his apparatus (2362 of 1857).

Though Harrison had commercial success establishing a second ice company back in Sydney in 1860, he later entered the debate of how to compete against the American advantage of unrefrigerated beef sales to the United Kingdom. He wrote Fresh Meat frozen and packed as if for a voyage, so that the refrigerating process may be continued for any required period.

In 1873, he prepared the sailing ship Norfolk for an experimental beef shipment to the United Kingdom. His choice of a cold room system instead of installing a refrigeration system upon the ship itself proved disastrous when the ice was consumed faster than expected. The experiment failed, ruining public confidence in refrigerated meat at that time. He returned to journalism, becoming editor of the Melbourne Age in 1867.

Harrison returned to Geelong in 1892 and died at his Point Henry home in 1893.

Source: Wikipedia

CHAPTER I. HISTORICAL.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF COLD STORAGE.

Mother earth as a source of available refrigeration, is without doubt a pioneer. In the Temperate Zone at a depth of a few feet below the surface, a fairly uniform temperature is to be obtained at all seasons of about 50° to 60° F. In some places a much lower temperature is obtained. The same principle is true in any climate, the earth acting as an equalizer between extremes of temperature, if such exist. Caves in the rock, of natural formation, are in existence, in which ice remains the year around, and many caves are used for the keeping of perishable goods. The even temperature, dryness and purity of the atmosphere to be met with in some caves are quite remarkable, owing no doubt to the absorptive and purifying qualities of the rock and earth, as well as to the low temperature obtainable.

CELLARS.

Cellars are practically artificial caves and if well and properly built are equally good for the purpose of retarding decomposition in perishable goods. A journey through the Western states reveals many farmers who are the possessors of "root-cellars," (usually detached from any other structure,) and considered a first necessity of successful farming, the new settler building his cellar at the same time as his log house.

A root-cellar is used partly as a protection against frost, but it also enables the owner to keep his vegetables in fair condition during the warm weather of the spring and summer months. The use of cellars for long keeping of dairy products is familiar to all. Many of us can recollect how our mothers put down butter in June and kept it until the next winter, and perhaps it will be claimed by some, that the butter was as good in January as when it was put down. It was not as good, far from it. If you think it was, try the experiment today and you will see how it will taste and how much it will sell for in January, in competition with the same butter stored in a modern freezer. The butter made years ago was no better either. No better butter was ever made than we are producing to-day. In short, cellars were considered good because they had no competition--they were the best before the advent of the improved means of cooling. Cellars are still of value for the temporary safe keeping of goods from day to day, or for the storage of goods requiring only a comparatively high temperature, but with a good ice refrigerator in the house, the chief duty of a cellar, nowadays, is to contain the furnace, and as a storage for coal and other non-perishable household necessities. To be sure cellars have their place as frost-proof storage in winter, but we are discussing the cooling problem here.

ICE.

The use of ice as a refrigerant during the summer months is a comparatively modern innovation, and not until the nineteenth century did the ice trade reach anything like systematic development. The possibility of securing a quantity of ice during cold weather and keeping it for use during the heated term seems not to have occurred to the people of revolutionary times. About 1805 the first large ice house for the storage of natural ice was built, and with a constantly increasing growth, the business rose to immense proportions in 1860 to 1870. The amount harvested is now much larger than at that time and constantly increasing, but the business is now divided between natural ice and that made by mechanical means.

The first attempt at utilizing ice for cold storage purposes was either by placing the goods to be preserved directly on the ice or by packing ice around the goods. These methods are in use at present as for instance in the shipping of poultry, fish and oysters, and the placing of fruit and vegetables on ice for preservation and to improve their palatability.

The first form of ice refrigerator proper consisted merely of a box with ice in one end and the perishable goods in the other. This form of cooler is illustrated in the old style ice chests, which are now mostly superseded by the better form of house refrigerator with ice near the top and storage space below. On a larger scale small rooms were built within and surrounded by the ice in an ice house. These rooms were of poor design and did not do good work, largely the result ot no circulation of air within the room. The principle of air circulation was recognized later, and by placing the ice over the space to be cooled, a long step in the right direction was taken. By this method the air was induced to circulate over the ice and down into the storage room. During warm weather a good circulation of air in contact with the ice purifies the air and produces a uniformly low temperature.

Many houses on this system are still in existence, although rapidly being superseded by improved forms.

About the time when the overhead ice cold storage houses were being installed freely, mechanical refrigeration came into the field. Mechanical refrigeration in which the storage rooms are cooled by frozen surfaces, usually in the form of brine or ammonia pipes, was much superior to ice refrigeration. in that the temperature could be controlled more readily and held at any point desired and that a drier atmosphere was produced. Ice and mechanical refrigeration will be discussed fully in treating of construction and in discussing the value of different systems for different purposes. It may be remarked in passing that ice is at present and will probably always remain a most useful and correct medium of refrigera-tion, especially for the smaller rooms and, under some con-ditions, large ones as well. The invention and introduction of the Cooper brine system using ice and salt for cooling marked an important step in ice refrigeration. This system is described in the chapter on "Refrigeration from Ice."

MACHINERY.

The first method of mechanical refrigeration to come into general use, and one which is still largely in use on ocean going steam vessels, was by means of the compressed air ma-chines. These operate by compressing atmospheric air to a high tension, cooling it, and expanding it. These machines are very uneconomical in that the compressed gas is not liquefied. Present practice in compression machines mostly employs either ammonia gas or carbon dioxide gas, both of which may be liquefied by pressures and temperatures readily obtainable. Other gases are in use also, but ammonia is the favorite as it liquefies more easily. The apparatus known as the absorption ammonia system is really a chemical rather than a mechanical process, but is usually classed along with the mechanical systems. In this system, the ammonia gas is driven off from aqua ammonia under pressure, by heating; the gas is liquefied by cooling, and the refrigerating effect obtained by expanding the liquid ammonia thus obtained through ripes surrounded by the medium to be cooled. This system is quite largely in use and preferred by many to the compression system, although the latter is used in a large majorit of plants.

Source: Practical cold storage ; the theory, design and construction of buildings and apparatus for the preservation of perishable products, approved methods of applying refrigeration and the care and handling of eggs, fruit, dairy products, etc by Cooper, Madison; 1914; Publisher Chicago, Nickerson & Collins

No comments:

Post a Comment