Settlement

.

A land sale at the north-west corner of Doncaster and Williamsons roads, 1888. Note the tower in the background to the left. (Photo: DTHS)

There is a certain pleasure to be derived from the prospect of human settlement in areas where thousands of years later, streets would be laid out and houses erected.

Peter Ackroyd, London: the biography (2000)

Settlement may be defined as the action of settling in a fixed or comfortable place. Without considerable human intervention and modification, how many places remain comfortable for any longer than the natural cycle of seasons allows? The flash and drive of human imagination expressed in urbanisation in the second half of the twentieth century has so greatly modified the place we call Manningham that it has become, for some people, a place where they settle through many seasons for the duration of their life. For the very first people who settled here, it could have been a comfortable place for the duration of all imagining people

Sketch of a memorial to Thomas Bungaleen, a Kurnai man from the Gippsland area who died of gastric fever in 1865, aged 18. He had been orphaned after he and his family were brought to Melbourne as hostages on a police raid. After some schooling, he worked as a messenger for the Lands Department and was then unhappily bonded to the steamship Victoria for several years, participating in its search for Burke and Wills, before being apprenticed as a draftsman. The memorial was engraved by Simon Wonga, ngurungaeta (headman) of the Woiwurrung, and represents his ‘kindly concern for a lonely lad who had spent his life among alien people’.The men in the upper part of the image are likely to be friends investigating Bungaleen’s death. The animals might indicate that he did not die due to lack of food, while the figures below the kangaroos are probably the Mooroops or spirits whose enchantments caused Bungaleen’s death. Source: R.E. Barwick and Diane E. Barwick, Memorial for Thomas Bungeleen', Aboriginal History, vol. 8, 1984, pp. 9-11

The first people

Until the European incursion into the region, its first people - the Wurundjeri - routinely moved around Manningham’s many comfortable sites in accordance with cultural patterns developed over many thousands of years, in pursuit of physical, intellectual and spiritual well- being. In summer, the river flats of the great course of water at the centre of their custodial lands - which came to be known as the Yarra River - were a very comfortable place for the Wurundjeri people to settle. The wildlife attracted to the billabongs formed by the river somewhat eased the pressure of hunting for food. Eels, for example, were usually in plentiful supply in the Bolin Swamp. With the advance of the wetter, colder seasons when the river was prone to flooding, the undulating country of the region, with its abundance of timber and fur-skinned animals, became the more comfortable place to settle for a time (Isabel Ellender, The City of Doncaster and Templestowe: the archaeological survey of Aboriginal sites (Doncaster, Victoria: Victoria Archaeological Survey; Dept of Conservation and Environment, c. 1991), p. 8.). Movement was a natural part of the settlement pattern for the Wurundjeri. With the coming of Europeans, that pattern was gravely and permanently disrupted.

What we know today of Wurundjeri social organisation before that time has been irrevocably affected by the history that followed. Knowledge was lost in the middle years of the nineteenth century as Wurundjeri (named by Europeans the 'Yarra tribe') were forced to live away from their land and suffered the early deaths of numerous family members. Within a very short time, there were only a few appropriate people to whom the elders could hand on their culture. Well-meaning Europeans (named by the Wurundjeri 'ngamajet') attempted to document aspects of Wurundjeri culture and language, but there were many subtleties and levels of sophistication they could not perceive or be told. Much of the knowledge that has survived was first filtered through a nineteenth-century western cultural perspective and then re-investigated in twentieth-century scholarship. In the continuing process of restoring and reclaiming such knowledge by Wurundjeri and other historians, a more accurate picture is only gradually emerging.

When Europeans first arrived in the district they named Port Phillip, the large fan-shaped bloc of territory from the coast to as far north as Euroa was owned and occupied by the five groups that formed the confederacy known as the Kulin nation. One of these groups, the Woiwurrung language group, had custodianship of the area drained by the Yarra River and its tributaries. In turn, five clans made up the Woiwurrung language group - Wurundjeri-willam, Wurundjeri-balluk, Marin-bulluk, Kurung-jang-balluk and Gunung- willam-balluk. The clan Wurundjeri-willam setded the area drained by the Yarra from its northern sources near Mount Baw Baw down nearly as far as the coast. This wide region reached from the eastern side of the Maribyrnong River as far north as Mount William (which was a regional flint axe mining centre that traded to all parts of Australia), and east following the edge of the Great Dividing Range, to the border with the Kurnai beyond Warburton; Wurundjeri-willam land included present-day Manningham. (Diane Barwick, ‘Mapping the past: an atlas of Victorian clans 1835-1904’, Aboriginal History, vol. 8, no. 2, 1984, pp. 120-124.)

About once in three months the whole tribe [clan] unite, generally at new or full moon, when they have a few dances, and again separate into three or more bodies, as they cannot get food if they move en masse; the chief, with the aged, makes arrangements for the route each party is to take ... They seldom travel more than six miles a day. In their migratory moves all are employed; children in getting gum, knocking down birds, &c; women in digging up roots, killing bandicoots, getting grubs, &c; the men in hunting kangaroos, &c, scaling trees for opossums, &c, &c. They mostly are at the encampment about an hour before sundown - the women first, who get fire and water, &c, by the time their spouses arrive. They hold that the bush and all it contains are mans general property; that private property is only what utensils are carried in the bag; and this general claim to natures bounty extends even to the success of the day; hence at the close, those who have been successful divide with those who have not been. There is no complaining in the streets' of a native encampment; so none lacketh while others have it; nor is the gift considered as a favour, but a right brought to the needy ...

Source: William Thomas, Assistant Protector of Aborigines for eastern Port Phillip area, 'Brief Account of the Aborigines of Australia Felix', in Bride ed., pp. 65-6.

A large bag or basket made of reed leaves which grew on the banks of the Yarra and Goulburn rivers. This sketch was made of a bag presented in 1840 to a European by the wife of Benbow, of the Yarra tribe. Source: Smyth, The Aborigines of Victoria, vol. I, p. 343

The clan was the social group with which an individual would first identify herself or himself, and clan identity was linked with a particular area of land and based on a permanent water course. As a clan was too large a group to manage for the organisational subtleties of day-to-day living, people usually traversed their land in smaller, family-based units. They stayed in close contact with other clan members and all would gather for important ceremonies or to share their harvest in bountiful times. All Kulin tribes were divided into four ritual groups known as skin groups and marriage partners were always selected from the appropriate skin group outside the clan, helping to ensure that political and social ties were maintained both across the Kulin and with people from further away. This was a complex social system born of ritual duty to the land and dependent on unfettered access to it in order to protect and manage it (Gary Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne: the lost land of the Kulin people (Ringwood, Victoria: McPhee Gribble, 1985, rpt 1994), pp. 37, 42-43). Traditional Kulin life had been indirectly disrupted by Europeans long before John Batman and his party sailed up the Yarra. The coastal reaches of Kulin territories had been encroached since the late eighteenth century by the base camps of whalers and sealers, as well as at least one short-lived attempt to establish a more permanent settlement; but it was the coming of European settlers that destroyed forever a style of life that had served the Kulin well for many thousands of years. In varying ways, Kulin people at this time of transition, followed by their descendants, made accommodations with the culture that had brought such permanent change.

The place for a village

The desire for more pasture land was the impulse behind the arrival of many of the earliest Europeans to settle the area. Land available for selection was diminishing in the island colony of Van Diemens Land to the south. Favourable reports of the Port Phillip district encouraged those with ambition and a little foresight to grasp the opportunity to secure more land. Batman had noted this will be the place for a village' in 1835. Because of the number of European settlers already moving into the district, the governor of the colony of New South Wales proclaimed Port Phillip as a district open to settlement in 1836. By 1837 Batmans village had been named Melbourne after the British Prime Minister and the settlements population had grown to over 500 people. Squatters, with great herds of grass-munching livestock, rapidly took over large tracts of Wurundjeri territory, increasingly preventing its traditional owners from living there (See C. M. H. Clark, ed., Select Documents in Australian History 1788-1850. (1950; rpt Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1980), Vol. I, pp. 89-95).The ensuing tension over access to the land on some occasions escalated to violence from both sides in the earliest years of European settlement. In other parts of the district, people were murdered and other atrocities were committed. While there is little documented evidence of violent deaths in the struggle over land within the territory of present-day Manningham, there were many cases of aggressive acts aimed at protecting access to land, ranging from burning paddocks to attacking individuals. As late as February 1860, for example, William White was tried at the Anderson’s Creek (Warrandyte) Police Court for shooting at an Aboriginal man named Bobby at Brushy Creek, and was fined £5 Tor discharging fire arms in a public place' (Notes from police records, cited in W. W. L. Radden, ‘The Early History of Warrandyte’, November 1965).

Some Wurundjeri adapted to the changing circumstances by participating actively in the newly developing economy. They worked for pastoralists in a wide range of tasks, from fencing and stockkeeping to harvesting. Particularly during the labour shortages following the gold rush of 1851, their assistance was vital on many properties. Much of this work, however, was seasonal, and as access to their lands became restricted, it was difficult to supplement earnings with subsistence hunting. Government edicts prevented most Wurundjeri from living close to Melbourne, and they were forced in many cases to live in unhealthy, miserable camps, periodically moving even further away as the land was taken over for European purposes. Within this context of severe social disruption, the impact of illness- es such as influenza, and for some people the effects of excessive alcohol consumption, meant that mortality rates were very high. At the same time, very few children were born or survived infancy - it seemed to sympathetic European observers such as William Thomas that people began to feel there was little point in having children once they no longer had their land. On one count, in the three decades to 1863 the Wurundjeri population plummeted from several hundred to barely more than twenty (Diane Barwick, Rebellion at Coranderrk, ed. Laura E. Barwick and Richard E. Barwick (Canberra: Aboriginal History Monograph 5, 1998), pp. 30-7. See also Gary Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne: the lost land of the Kulin people (Ringwood, Victoria: McPhee Gribble, 1985, rpt 1994), p. 104).

Meanwhile, various government-appointed officials and boards attempted to assist Kulin people with some gesture towards compensation for their lost lands. For more than twenty years after his appointment in 1839 as an assistant to the Chief Protector of Aborigines in the area, William Thomas had responsibility for assisting the Woiwurrung and Bunurong clans.

He worked with Wurundjeri leaders (or ngurungaeta) - in particular Billibellary, then his son Simon Wonga - to arrive at acceptable options for their people. Initially, Thomas’s work included ensuring that rations of food and blankets were available to those in urgent need - one little-used depot for such rations was located from 1852 to 1860 in the Aboriginal Reserve of over 1,000 acres near Warrandyte (See Murray Houghton, ‘The Warrandyte Aboriginal Reserve - established when?’ Discussion paper, Warrandyte Historical Society, December 2000).

By the late 1850s, many Kulin people wished to secure some of their remaining land in order to be able to farm and be self-sufficient. Despite active support from Thomas, they endured the frustration of several short-lived ventures due to inadequate government support and the demands of nearby European settlers leading to the revoking of reserved lands. In 1863, however, they successfully established a farm and township on 2,300 acres at Coranderrk near Healesville, on land that bordered Woiwurrung, Bunurong and Taungurong country. The hop farm they developed was initially a success, its produce winning first prize at the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1872. Under the leadership of William Barak, who succeeded his cousin Simon Wonga as ngurungaeta in 1874, the Coranderrk community withstood many difficulties and tragedies (See Diane Barwick, Rebellion at Coranderrk, ed. Laura E. Barwick and Richard E. Barwick (Canberra: Aboriginal History Monograph 5, 1998), pp. 30-7. See also M. H. Fels, Some Aspects of the History of Coranderrk Station (Melbourne: Aboriginal Affairs Victoria, c. 1999), and Shirley Wiencke, When the Wattles Bloom Again: The Life and Times of William Barak, Last Chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe (Woori Yallock: Shirley W. Wiencke, 1984).

Barak at Coranderrk, around 1895. (RHSV)

Vicki Nicholson, whose mother belonged to the last generation to be born at Coranderrk, has written about the attempts made by many of its residents to make lives for themselves within its constraints:

The men laboured hard, the women worked at handicrafts and sewing and the children spent many hours in the school. William Barak, the last tribal chief of the Yarra Yarra tribe of the region is believed to have been an intelligent and influential man. ... At first, a great deal of effort was put into preparing the land and establishing farmland to feed the community. ... Green, the manager, had encouraged Barak and the others to work hard at it, saying they could look forward to a future as a self-sufficient little community. ... [In 1867] the Board took over control of revenue and paid the men for their work by paying their wages to the manager, who in turn provided them with money for necessities and special purchases. The people of Coranderrk felt threatened by the Board taking all this control, so much so that they were beginning to worry about losing their land. ... The government continually threatened to close Coranderrk and this caused a period of unrest. They gradually lost their land, and it was taken bit by bit as the 10 farmers had pushed for it. ... The Aboriginal people of Coranderrk developed a resistance to the Board for Protection of Aboriginals because of its interference in their lifestyles and their welfare. Around 1875, authorities came up with the notion that Coranderrk should be closed down. Barak and his people were not going to be pushed off their homelands. ... Barak used to take his people straight to Melbourne and the Board for Protection of Aboriginals felt threatened with his actions because they went over the authority’s head by doing so (Vicki Nicholson, ‘Coranderrk’, MOSA (Monash Orientation Scheme for Aboriginals Clayton Campus) Magazine, no. 1, c1985, pp. 30-2).

Changes in government policy, including restrictions on those with any European ancestry living on such reserves, led eventually to the official closure of Coranderrk in early 1924. Many of its residents were forced to move to Lake Tyers. Others continued to live in the Healesville area.

The men laboured hard, the women worked at handicrafts and sewing and the children spent many hours in the school. William Barak, the last tribal chief of the Yarra Yarra tribe of the region is believed to have been an intelligent and influential man. ... At first, a great deal of effort was put into preparing the land and establishing farmland to feed the community. ... Green, the manager, had encouraged Barak and the others to work hard at it, saying they could look forward to a future as a self-sufficient little community. ... [In 1867] the Board took over control of revenue and paid the men for their work by paying their wages to the manager, who in turn provided them with money for necessities and special purchases. The people of Coranderrk felt threatened by the Board taking all this control, so much so that they were beginning to worry about losing their land. ... The government continually threatened to close Coranderrk and this caused a period of unrest. They gradually lost their land, and it was taken bit by bit as the 10 farmers had pushed for it. ... The Aboriginal people of Coranderrk developed a resistance to the Board for Protection of Aboriginals because of its interference in their lifestyles and their welfare. Around 1875, authorities came up with the notion that Coranderrk should be closed down. Barak and his people were not going to be pushed off their homelands. ... Barak used to take his people straight to Melbourne and the Board for Protection of Aboriginals felt threatened with his actions because they went over the authority’s head by doing so (Vicki Nicholson, ‘Coranderrk’, MOSA (Monash Orientation Scheme for Aboriginals Clayton Campus) Magazine, no. 1, c1985, pp. 30-2).

Changes in government policy, including restrictions on those with any European ancestry living on such reserves, led eventually to the official closure of Coranderrk in early 1924. Many of its residents were forced to move to Lake Tyers. Others continued to live in the Healesville area.

Many places in Manningham reflect Wurundjeri names or phrases. For example:Bullen bullen: lyrebirdKoonung koonung: muddy water Mullurn mullum: large birdWarrandyte: warren (to throw) + yte (verbal ending)Wonga: native pigeonYarn: always flowing’, waterfall’, ‘red gums’, ‘hair’or ‘spirit woman’Source: translations courtesy of Bill Nicholson.

The Parish of Bulleen

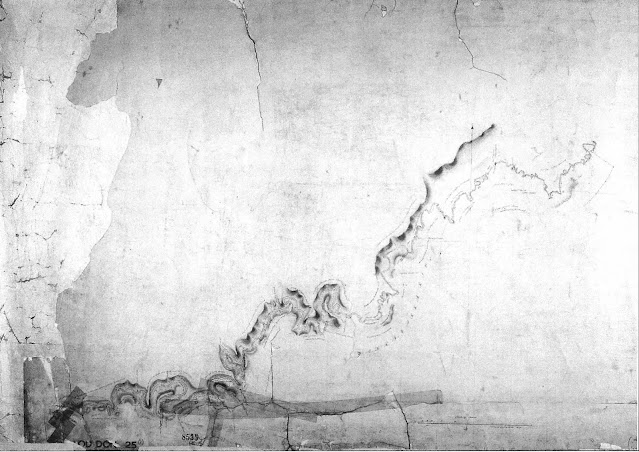

Part of the Wurundjeri-willam lands were named the Parish of Bulleen in 1837 when government surveyor Robert Hoddle surveyed the region between the Yarra River and Koonung Creek. Two years later Hoddle sent his assistant, T. H. Nutt, deeper into the valley to survey the Plenty and Yarra rivers. Hoddle wanted a plan of the Yarra’s main branches, and once that was done Nutt was told to track the river’s tributary streams and watercourses. The terrain was difficult and the conditions under which Nutt and his team had to make the survey were trying. By May 1839 Nutt had completed his survey of the river nearly as far as Mr Gardiners second station and found the banks in general to be exceedingly scrubby, mountainous & thickly timbered'.10 The map Nutt produced after this excursion seems to be the first official survey of the Upper Yarra district that included Manningham’s regions. On the map Nutt noted sites along the river where several Europeans had established grazing runs - Newmans Sheep Station, William Woods Sheep Station, Anderson’s Sheep Station, cMr Gardiner’s Cattle Station' and 'Messrs Ryrie’s Cattle Station' are all identifiable there. Not shown on Nutt’s 1839 map, but believed to have arrived in the district not long after the Woods, were the Ruffy brothers. They set up a sheep run, north of John Wood’s sheep station, to use as a holding point for their stock that was to be sent to market in Melbourne (Judith Leaney, Bulleen: a short history (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, c. 1991), p. 6. It is believed the Ruffys’ run was located on the present site of the Yarra Valley Country Club). These names provide a useful place for us to start detailing aspects of the beginning of the European settlement of Manningham - a process that continues into the present day.I have applied for two months rations, for after I have passed Mr Ryrie's station it will take the dray at least a fortnight or more to go up & down from the settlement, the roads are so dreadfully bad, in fact if wet weather sets in, it will be impossible for horses to come up with a load. As it is we have had great trouble …. The mountains next to Mr Ryrie’s are next to impassable, and I understand farther up they are so much worse. ... I intend asking the favour of Mr Ryrie allowing me to leave one months rations at his station, as I shall not be able to carry two months’over the mountains, with my present team. ... I also beg to draw your attention to my men being without blankets. The cold and dampness arising from the river is very great, and will be much more so the farther we go on, and all with the exception of two have colds and are otherwise ill. Source: T. H. Nutt to Robert Hoddle, 26 May 1839, cited in Cannon and Macfarlane, pp. 365, 370

Map by T. H. Nutt (Loddon 25 1, Yarra Yarra No. 1) made in 1839. (Reproduced by the courtesy of the Surveyor-General, Victoria and the Keeper of the Public Records)

The overlanders

On the 15th January 1838, I started from Strathallen, county St Vincent, New South Wales, with 1,400 ewes, 50 rams, 200 wethers, 2 drays, 18 bullocks; 10 men (all prisoners of the Crown); 1 cart and horse, 1 saddle horse, 2 brood mares, private property; and Mr Hawdon, and two children. ... Mr William Coghill had mustered his sheep on the Murrumbidgee, to accompany me to Port Phillip about the end of the month ... Mr William Bowman overtook us, and arrangements were entered into for the three parties to keep company until all were satisfactorily settled in the new country. ... Mr Bowman had about 5,000 sheep, Mr Coghill 2,000, making, with my lot, in all near 9,000. Source: John Hepburn, who settled at Smeaton Hill, writing to Lieutenant Governor Charles La Trobe, 10 August 1853, cited in Bride, pp. 51-2

John Gardiner is believed to have been one of the first Europeans to explore the Upper Yarra valley. A banker in Van Diemens Land, Gardiner also had pastoral interests there and in New South Wales. He first visited Port Phillip in early 1836, coming across Bass Strait on board the Norval. He brought with him a cargo of sheep, a number of which perished on the journey. Such stock losses possibly prompted many pioneer pastoralists who were considering extending their holdings into the Port Phillip district to herd new stock overland from New South Wales rather than import them from Van Diemen s Land. Impressed by the potential he saw in the pasture land of the Port Phillip district, Gardiner went to New South Wales and arranged to drive some cattle overland to the new colonial outpost later that year. Gardiners first stock run was not in Manningham. He grazed his cattle on grasslands now covered by Hawthorn, Camberwell and Kew (Geoffrey Blainey, A History of Camberwell (Melbourne: Jacaranda Press, 1964), p2). Gardiners Creek, previously called Kooyongkoot Creek, which runs into the Yarra at Hawthorn, now carries his name (Andrew Taylor, The Day We Lost Forever (Balwyn: Rivka Frank & Associates, 1988), Introduction).

It is believed that Gardiner became aware of Upper Yarra grazing land while searching for some stock that had strayed from his Hawthorn lease. He soon after registered a second lease covering 5,700 hectares, extending from Brushy Creek to the west to todays Olinda Creek to the east, and from the Yarra River to the foothills of the Dandenongs (G. F. James, Border Country: episodes and recollections of Mooroolbark and Wonga Park ([Lilydale, Victoria]: Shire of Lillydale, 1984), p. 9). This lease is what Nutt referred to as Mr Gardiner's second station. While Gardiner was a significant influence on the early settlement of the region, he did not himself settle in Manningham and eventually returned to England permanently. That he did not stay long in the area was partly for reasons of safety - he and his men had a poor relationship with the local Wurundjeri, in one instance shooting at and taking some people prisoner for stealing potatoes (Andrew Taylor, The Day We Lost Forever (Balwyn: Rivka Frank & Associates, 1988), Postscript).

It is known that Major Newman was dour, harsh and single minded in all that he did. One story that has been passed down our family concerns when the local tribe decided to rid themselves of the Major once and for all. A raiding party approached the Major’s house ... Seeing the natives coming [his wife] got the Major to hide up the chimney and lit the fire underneath him. The tribesmen came into the house armed with clubs and spears but when they could not find the Major they finally left. He then climbed down, his clothing and whiskers having been singed by the heat of the fire. Source: Hazel Poulter, Templestowe: a folk history p.3.

The Wood brothers, John and William, are believed to have been the first Europeans actually to settle in the Manningham region. They, too, had crossed from Van Diemens Land, possibly as early as 1837, to set up a sheep farm. By 1839 the brothers had established runs in two different places in the region. John Wood occupied a site on the Yarra River flats of Bulleen, while his brother William settled at Warrandyte (See Michael Cannon and Ian Macfarlane, eds, Surveyors Problems and Achievements, 1836-1839, Vol. V of Historical Records of Victoria: foundation series (Melbourne: Public Record Office, 1988), p. 133 and pp. 366-7 for William and pp. 138-9 for John Wood). The location of William Woods station is shown on Nutts 1839 map. The Wood brothers may have been the first Europeans to settle in Manningham but their stay was brief. By 1841 they had moved elsewhere (Graham Keogh, The History of Doncaster and Templestowe (Doncaster, Victoria: City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1975), p. 5).

Further upstream from Warrandyte on his survey map of the £Yarra Yarra River', after he notes 'Mr Gardiners Cattle Station, Nutt has written 'Messrs Ryrie’s Cattle Station. The Ryrie brothers, William, Donald and James, held a grazing lease of 30,000 acres just beyond Gardiner’s second run, in the area of Manningham called Wonga Park. The brothers had over- landed their stock at about the same time as Gardiner, and it is believed they registered their holding around 1837. They remained associated with the district longer than the Wood brothers, but by 1850 the Ryrie holding had also been taken over by someone else (G. F. James, Border Country: episodes and recollections of Mooroolbark and Wonga Park ([Lilydale, Victoria]: Shire of Lillydale, 1984), p. 9. James argues that it was Paul de Castella who took over the Ryrie holding in 1850).

Of the five names mentioned above as being marked on Nutts 1839 map (Anderson, Wood, Newman, Gardiner and Ryrie), the only one to remain and farm in the region for a substantial length of time was Major Charles Newman. Newman, who had served as Officer Commanding the 51st Bengal Native Infantry of the East India Company, retired from the army in 1834 and settled in Van Diemens Land. In 1837 he crossed Bass Strait and selected land at the junction of the Mullum Mullum Creek (then Deep Creek) and the Yarra. Here he built his wealth running both sheep and cattle. Starting with a turf hut, in time he was able to complete construction of a homestead which he called Pontville (‘Historical research and investigation of the building fabric reveals and confirms an early date for the present Pontville house, probably as early as 1843-1850.’ Context Pty Ltd et ah, Pontville: Cultural Significance and Conservation Policy (Melbourne Parks and Waterways; City of Manningham, June 1995), p. iv). The homestead still stands near Blackburn Road in Templestowe. While his pioneering spirit and perseverance are to be commended, Newman, unfortunately, is also an example of an early settler whose attitudes did little to forge good relations with the indigenous people of Manningham. Newman lived and worked in the district for eighteen years. He eventually owned 640 acres of freehold land, leased a further 10,000 in the region, and by 1852 had built a second home- stead that he named Monckton, now substantially demolished. As well as grazing cattle and sheep, Newman and his family successfully bred Welsh ponies on his property and owned racehorses. He also took an active interest in the colony of Victoria's separation from New South Wales. By 1855 he had left the district to live his final days in Hawthorn (Poulter, Templestowe: a folk history, pp. 2-4).

James Anderson’s Warrandyte run, too, is noted on Nutt’s 1839 map. He and his wife, Ann, are believed to have arrived from Van Diemen’s Land either in 1837 or 1838. Anderson grazed his cattle on land selected upstream from Newman’s run but was often feuding with 14 his neighbour over encroachments into each others holdings. In those early days of settlement, no clear property boundaries were established. Like the Wood brothers, Anderson did not stay long in the district. After Nutts second survey of the area, undertaken in 1841 to delineate the boundaries of the 'Parish of Warran-Dyte' in the 'County of Bourke', Anderson’s run was reduced to only 390 acres. Soon afterwards he quit the district, leaving Newman to expand his run into that acreage. His significance regarding the early settlement of the district is remembered, however, in the naming of Anderson’s Creek (Bruce Bence, Warrandyte: a short history ([Warrandyte, Victoria]: Warrandyte Historical Society, 1991), pp. 2-4. ‘Anderson’s Creek’ was written in the nineteenth century with the possessive apostrophe. More recently the apostrophe has been dropped).

Though neither stayed long, both Anderson and the Wood brothers provide a link to the next phase of settlement in the Manningham region. A sketch map titled 'Anderson’s Run on the Yarra Yarra', which James Anderson included with a letter he wrote on 2 October 1842, shows the site of his run. Further upstream from his property, Anderson has marked 'Dawson’s station' and on the other side of Jumping Creek he has drawn 'Selby’s station' (Public Record Office - VPRS 6760, available on microfilm as VPRS 4467). When the Wood brothers moved on, around 1841, the property was secured by a Scotsman, Robert Laidlaw. All three parties, Laidlaw, the Dawsons and the Selbys, are representative of the next phase of European settlement in the district. They were not overlanders; they came from over the sea, but not from Van Diemen’s Land. Their ports of exit were much further away.

The tide of European settlers into Manningham, which began to gather momentum around 1840, was bolstered by immigration. When the earliest colonial authorities realised that convict labour alone could not meet the growing colonies' labour needs, they looked to immigration to provide the solution. In the second quarter of the nineteenth century nearly three million people left the difficult social conditions of Great Britain, migrating to various parts of the 'New World'. One way of attracting potential immigrants to the Port Phillip colony was through publications describing the successful lives of recent migrants in glowing terms; in his book Phillip stand, for example, the Reverend J. D. Lang told British readers that the region was 'in the highest degree conducive to the physical comfort and happiness of man' (Cited in Richard Broome, The Victorians: arriving (Melbourne: Fairfax Syme & Weldon & Associates, 1984), pp. 44-3). Robert Laidlaw, who in time would become one of Manningham’s most prominent and successful early citizens, arrived at Port Phillip from Scotland in 1839 aboard the Midlothian, the first ship to bring Scottish immigrants to this new outpost of the colony of New South Wales. Born in 1816 near Abbotsford in Scotland, Laidlaw worked, from the age of 16, on the estate of famed Scottish writer Sir Walter Scott. Then, at the age of 23, he decided to try his luck in Australia (From privately collected material held by Illona Caldow, a former co-owner of Clarendon Eyre. See also Graham Keogh, The History of Doncaster and Templestowe (Doncaster, Victoria: City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1975), p. 5). We cannot say what Laidlaws first months in the colony were like. Eventually he went into partnership with Alexander Duncan, who had also travelled to Port Phillip on the Midlothian (His daughter, Isabella, married George Smith. They built Ben Nevis. See Irvine Green, Petticoats in the Orchard (Doncaster, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, 1987), p. 4), By the time they formed this partnership, Duncan had already established a dairy farm near the corner of Thompson and Bulleen roads (Judith Leaney, Bulleen: a short history (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, c. 1991), p. 11).

Further upstream from Warrandyte on his survey map of the £Yarra Yarra River', after he notes 'Mr Gardiners Cattle Station, Nutt has written 'Messrs Ryrie’s Cattle Station. The Ryrie brothers, William, Donald and James, held a grazing lease of 30,000 acres just beyond Gardiner’s second run, in the area of Manningham called Wonga Park. The brothers had over- landed their stock at about the same time as Gardiner, and it is believed they registered their holding around 1837. They remained associated with the district longer than the Wood brothers, but by 1850 the Ryrie holding had also been taken over by someone else (G. F. James, Border Country: episodes and recollections of Mooroolbark and Wonga Park ([Lilydale, Victoria]: Shire of Lillydale, 1984), p. 9. James argues that it was Paul de Castella who took over the Ryrie holding in 1850).

Of the five names mentioned above as being marked on Nutts 1839 map (Anderson, Wood, Newman, Gardiner and Ryrie), the only one to remain and farm in the region for a substantial length of time was Major Charles Newman. Newman, who had served as Officer Commanding the 51st Bengal Native Infantry of the East India Company, retired from the army in 1834 and settled in Van Diemens Land. In 1837 he crossed Bass Strait and selected land at the junction of the Mullum Mullum Creek (then Deep Creek) and the Yarra. Here he built his wealth running both sheep and cattle. Starting with a turf hut, in time he was able to complete construction of a homestead which he called Pontville (‘Historical research and investigation of the building fabric reveals and confirms an early date for the present Pontville house, probably as early as 1843-1850.’ Context Pty Ltd et ah, Pontville: Cultural Significance and Conservation Policy (Melbourne Parks and Waterways; City of Manningham, June 1995), p. iv). The homestead still stands near Blackburn Road in Templestowe. While his pioneering spirit and perseverance are to be commended, Newman, unfortunately, is also an example of an early settler whose attitudes did little to forge good relations with the indigenous people of Manningham. Newman lived and worked in the district for eighteen years. He eventually owned 640 acres of freehold land, leased a further 10,000 in the region, and by 1852 had built a second home- stead that he named Monckton, now substantially demolished. As well as grazing cattle and sheep, Newman and his family successfully bred Welsh ponies on his property and owned racehorses. He also took an active interest in the colony of Victoria's separation from New South Wales. By 1855 he had left the district to live his final days in Hawthorn (Poulter, Templestowe: a folk history, pp. 2-4).

James Anderson’s Warrandyte run, too, is noted on Nutt’s 1839 map. He and his wife, Ann, are believed to have arrived from Van Diemen’s Land either in 1837 or 1838. Anderson grazed his cattle on land selected upstream from Newman’s run but was often feuding with 14 his neighbour over encroachments into each others holdings. In those early days of settlement, no clear property boundaries were established. Like the Wood brothers, Anderson did not stay long in the district. After Nutts second survey of the area, undertaken in 1841 to delineate the boundaries of the 'Parish of Warran-Dyte' in the 'County of Bourke', Anderson’s run was reduced to only 390 acres. Soon afterwards he quit the district, leaving Newman to expand his run into that acreage. His significance regarding the early settlement of the district is remembered, however, in the naming of Anderson’s Creek (Bruce Bence, Warrandyte: a short history ([Warrandyte, Victoria]: Warrandyte Historical Society, 1991), pp. 2-4. ‘Anderson’s Creek’ was written in the nineteenth century with the possessive apostrophe. More recently the apostrophe has been dropped).

Though neither stayed long, both Anderson and the Wood brothers provide a link to the next phase of settlement in the Manningham region. A sketch map titled 'Anderson’s Run on the Yarra Yarra', which James Anderson included with a letter he wrote on 2 October 1842, shows the site of his run. Further upstream from his property, Anderson has marked 'Dawson’s station' and on the other side of Jumping Creek he has drawn 'Selby’s station' (Public Record Office - VPRS 6760, available on microfilm as VPRS 4467). When the Wood brothers moved on, around 1841, the property was secured by a Scotsman, Robert Laidlaw. All three parties, Laidlaw, the Dawsons and the Selbys, are representative of the next phase of European settlement in the district. They were not overlanders; they came from over the sea, but not from Van Diemen’s Land. Their ports of exit were much further away.

Free and virtuous migrants

This colony is made the receptacle for the outcasts of the United Kingdom, and is consequently loaded with a vast disproportion of immoral people. That the Colonists have derived many advantages from the transportation of Convicts, cannot be denied but the system has brought with it a long train of moral evils, which canonly be counteracted by an extensive introduction of free and virtuous inhabitants ... Source: Report of Committee on Immigration, 1835, cited in Clark, p. 194.

Selkirk Jany. 22nd 1839 - The bearer Mr Robert Laidlaw, is the son of truly respectable parents, has always maintained an exemplary character and enjoys, fully I believe, the esteem of all who are acquainted with him. He proposes immediately to emigrate to Australia, and I am happy to bear ample testimony to his religious and moral deportment. His probity [and] steadiness ... will, I have no doubt, give the greatest satisfaction to all with whom he may have intercourse or connection. of his knowledge of sheep, in the care of which he has been generally engaged, I cannot personally speak, as I am quite ignorant of that brand of rural economy. But I know that he is much esteemed in that respect also, by those who are qualified to judge. ... I trust his success will be equal to what I sincerely think his character deserves. Source: G. Lawson, Minister of the United Secession Church, Selkirk, from privately collected material held by lllona Caldow, a former co-owner of Clarendon Eyre.

Laidlaw selected land along the Bulleen Road and planted crops of wheat and barley. This venture was successful enough by 1847 for Laidlaw to gain recognition in Edinburgh for the quality of his produce. By 1857, a parcel of wheat grown on his farm won a medal, was sold in Melbourne at forty shillings a bushel and shipped to London and exhibited (From privately collected material held by Illona Caldow, a former co-owner of Clarendon Eyre). Like Major Newman, Laidlaws success enabled him to build for his family an impressive home, that he named Springbank. Known these days as Clarendon Eyre, the house, which was built in 1879, still stands in Robb Close, Bulleen. Robert Laidlaw was an early Manningham settler who also contributed greatly to the development of the region by directly participating in local government, first on the Road Board and then as a member of the Bulleen Shire Council (Council Minute Books, Shire of Bulleen 1875 - 1880, passim).

The Dawsons and Selbys did not experience the same measure of success as Laidlaw. Penelope Selby arrived in Port Phillip with her husband, George, and two young sons, Prideaux and William, in 1840. The Selby family had travelled from England on board the China, and during the journey the Selbys became close friends with fellow immigrants, James and Joan Dawson. By the time the China had docked at Port Phillip the two families had agreed to be neighbours, if possible, at wherever they chose to make their new start in the colony of New South Wales. Optimism was high. On 26 December 1840, Penelope Selby wrote to her grandparents:

I do not think I could live in London now, the air is so fresh here ... I [will] tell you in a few words what I think of this place. Any one, like ourselves, willing to work ... and put up with a few inconveniences and discomforts, let them come; but to the poor industrious mechanic or labourer and his wife and family the advantage is beyond description and I would not hesitate to say none would regret leaving England. ... 16 A person in want of food is a thing not known. I saw no beggar while I was in Melbourne ... Source: Letter from P. Selby to her grandparents, 26 December 1840, cited in Lucy Frost, No Place For a Nervous Lady: voices from the Australian bush (1984; rpt St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1999), pp. 115-16

The Selbys took up land near the junction of Anderson’s Creek and the Yarra River, not in partnership with but on the same place with Mr & Mrs Dawson. (30 Letter from P. Selby to her grandparents, 26 December 1840, cited in Lucy Frost, No Place For a Nervous Lady: voices from the Australian bush (1984; rpt St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1999), p. 115) By 1841 they were settled in separate residences on a station, which they named Bonny Town. (31 New South Wales Census of the Year 1841, return no. 21. (Copy held at Warrandyte Historical Society.)) Penelope Selby wrote with confidence about their prospects for success. She explained to her sisters how they planned to make their income:

George is now milking six cows, and if we can get a boy I intend to send fresh butter to Melbourne as soon as ever the weather is a degree cooler, I expect to get 2/6 a lb for it, and if I could only make a dozen pounds per week it would more than pay all our expenses. Source: 32 Letter from P. Selby to her sisters Mary and Kate, 26 January 1841, cited in Lucy Frost, No Place For a Nervous Lady: voices from the Australian bush (1984; rpt St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1999), p. 117

Her optimism had not diminished by 1842, despite some of the hardship that her new life entailed. Raised in England with expectations of leading a genteel, middle-class life, she had had to learn in Australia how to cure meat, make cheese, fatten calves and pigs, and cook kangaroo and possum. She was doing call the baking, washing and everything' even in the eighth month of her third pregnancy, which sadly ended with a stillbirth. When in 1842, having passed through the wettest winter ever known here', a winter when the Yarra River burst its banks and they could not go out of the house for months without being ankle deep', the constant mud turning the house into a pigsty', Penelope could still write that when clean it is such a nice little place'. (33 Letter from P. Selby to her sisters, 21 November 1842, cited in Lucy Frost, No Place For a Nervous Lady: voices from the Australian bush (1984; rpt St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1999), pp. 123-4) In the same letter, however, she indicated that things in the business line are in a most wretched state. Almost every merchant in Melbourne is failing.' The depression of the 1840s was beginning to bite. In the Selbys' case it was a drop in the price of butter that affected their livelihood. Within sixteen months the price given by merchants for butter halved, dropping from two shillings a pound to around one shilling. (34 Letters from P. Selby to her sisters, 5 July 1841 and 21 November 1842, cited in Lucy Frost, No Place For a Nervous Lady: voices from the Australian bush (1984; rpt St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1999), pp. 120, 122) The impact of such a reduction on the Selbys' income is obvious. The economic hardships that ensued so affected both families at Bonny Town that by 1844 they gave up their Warrandyte holding and together moved to a property James Dawson had acquired in Port Fairy. (35 Letter from P. Selby to her sisters, 6 November 1844, cited in Lucy Frost, No Place For a Nervous Lady: voices from the Australian bush (1984; rpt St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1999), p. 127)

Sidney Ricardo arrived in Port Phillip from London in 1843. He bought or leased 150 acres of farmland on the river flats at Bulleen and established a market garden. The site of his farm is now part of Banksia Park. (36 Context Pty Ltd et al., City of Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: general report prepared for the City of Doncaster and Templestowe (Melbourne: Context Pty Ltd, 1991), p. 23) In time Ricardo undertook to represent his fellow citizens in government. He led the push for the establishment of a local Road Board, and when this was achieved, became elected as its first chairman. He then went on to represent the community as MLA for South Bourke from 1857 to 1859. He was a vigorous advocate for the smaller farmer, arguing that the large tracts of land held by squatters be carved up into smaller parcels for more equitable use in agricultural ventures. A river red gum tree, presently in the forecourt of a service station at Bridge Street, marks part of the site where he farmed. (37 Judith Leaney, Bulleen: a short history (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, c. 1991), pp. 14, 16)

A smaller holding

Ben Nevis was built in 1890 in Bulleen for George Smith, whose family were dairy farmers. (Photo: DTHS).

Banksia Park, Bulleen, 2001. (Photo: Helen Penrose)

Many migrants who came into Manningham in the 1840s did not take up large tracts of land as squatters. Nor did they necessarily have the financial backing to set themselves up with livestock. Instead they eked out a living by labouring for the larger landholders while clearing their leased portions of Crown land in the hope of eventually setting up a small farm. Before they could farm they often had to clear the land, so another source of income for these early settlers came from selling wood in Melbourne, where that city’s expanding population provided a ready market.

One such early settler was John Chivers. On 29 June 1840, with his wife Mary Ann and baby son William, Chivers sailed from Plymouth in England on board the Himalaya, arriving in Port Phillip in the September that same year. In his homeland Chivers had built up his own business as a haulage specialist. On the ships register, however, he described himself as an agriculturist'. This apparent change of occupation probably reflects the skills migrants to the Australian colonies were preferred to possess, and which he could claim having grown up on a farm. John Chivers began his working life in the district as a woodcutter for Major Newman, while his wife worked as governess to the Newman children. In April 1842, Chivers squatted on Crown land on the river flats near the end of Fitzsimons Lane. There he cut timber, burnt charcoal and grew crops. He then regularly transported his produce to Melbourne for sale. (38 Poulter, Templestowe: a folk history, p. 6)

In terms of the new settlers' relationships with indigenous people, he proved to be the antithesis of Newman. John Chivers established strong friendships with local Wurundjeri, learning their language and exchanging food and other resources with them. When Mary Ann died in 1850, leaving him with four young children, the local Aboriginal people cared for the older boys, as his descendant Jim Poulter recounts: cMy grandfather Tom and his older brother Willie would go off and play all day with the Aboriginals. After his mother died, Tom spent a lot of time with the tribe going on walkabout - apparently he went to a special ceremony at Mount Macedon and walked all the way when he was only about six or eight. He was treated as one of the tribe and he spoke the language like a native and maintained lifelong friendships' (39 Jim Poulter, interview, 22 June 2001) John Chivers extended his holdings in the district in the 1850s, purchasing acreage first around Porter Street in the vicinity of Church Road.

All the early settlers mentioned above are representative of the many immigrants who, in the earliest days of settlement beyond the environs of the new town of Melbourne, pushed their way into the bush and carved out a space for themselves and their families. Other more entrepreneurial types of the time took advantage of the opening-up of the region in a manner quite different from farming.

The first Crown land to be sold by the Colonial Government in the Parish of Bulleen was a 5,120-acre lot between the Yarra River and Koonung Creek that became known as Unwins Special Survey. In March 1841 Sydney solicitor Frederick Wright Unwin took advantage of a generous government decree which stated that up to eight square miles of Crown land could be purchased, by approved persons, for £1 per acre provided the allotment was at least five miles from a surveyed township. For £5,120 Unwin obtained a tract of land that today includes Manningham's suburbs of Bulleen, Doncaster, Lower Templestowe and a large portion of Templestowe. A dispute regarding the Special Survey was eventually resolved in Unwins favour, but in the meantime he had sold out to James Atkinson. (40 Ken Smith, ‘Unwin’s Special Survey’, read before members of the Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, 1 October 1980)

A new Crown grant was issued in Atkinsons name and the land, which Atkinson renamed the Carleton Estate, was subdivided into farms - most of which had water frontages to either the Yarra River or the Koonung Creek. A plan, dated 18 November 1843, of part of the Parish of Bulleen shows lots available for selection varying in size from 640 acres to 1,057 acres. A note written on the plan says that several lots were offered for sale on 20 March 1844 at £1 per acre but that no bids were received.(41 Graham Keogh, The History of Doncaster and Templestowe (Doncaster, Victoria: City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1975), p. 4) Atkinson then leased the land to a property agent, who in turn sublet the lots. Eventually Atkinson sold the Carleton Estate to Robert Campbell in 1851 - the year when Victoria became a colony in its own right and when it was publicly announced that gold had been discovered not far from Melbourne.

Throughout Manningham in the 1850s the isolation of the earliest settlers began to diminish with the development of pockets of villages. As we have already noted, the settlement of Warrandyte received some impetus from the discovery in 1851 of gold at Anderson’s Creek; but it was not until 1856 that a township at Warrandyte was surveyed, by Clement Hodgkinson. (46 Context Pty Ltd et al., City of Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: general report prepared for the City of Doncaster and Templestowe (Melbourne: Context Pty Ltd, 1991), p. 42) Land in Warrandyte was sold during the 1850s in one-square-mile sections at the rate of £1 per acre. Much of Warrandyte South was also sectioned in 1856. (47 Irvine Green and Beatty Beavis, Park Orchards: a short history (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, 1983), pp. 3-4) If you look at the 1858 Parish of Warrandyte Map it shows the sections of 640 acres, each of which were occupied by selectors such as George King Thornhill, Francis Cooke, Charles Heape - with plans for a few roads. There was no road from Warrandyte to South Warrandyte, only a road from Ringwood to Wonga Park/Croydon. The area was only really opened up when sections each side of the Main Road at Parsons Gully were surveyed around 1914.' (48 Murray Houghton, personal communication, June 2001) In 1852, however, surveyor Henry Foote set out a grid of streets that would become the village of Templestowe. In November of that year grazing leases were cancelled and a land sale of village lots took place - the average price for a half-acre lot was £40. (49 Context Pty Ltd et al., City of Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: general report prepared for the City of Doncaster and Templestowe (Melbourne: Context Pty Ltd, 1991), p. 42) The grid pattern of streets is still easy to discern in Lower Templestowe. Streets in the village were named in honour of some of the districts earliest pioneers. Gently undulating streets running east-west carry names like Unwin, Atkinson, Wood and James; steeply sloping north-south streets honour Ruffy (misspelt 'Ruffey' when the street was named) Newman, Anderson and Duncan amongst others. (50 Irvine Green, Templestowe: the story of Templestowe and Bulleen (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, 1982), p. 5) East of the Carleton Estate, two square miles of land along what would become Doncaster Road was purchased by W. S. Burnley in 1853. He centred the grid plan of his subdivision on the junction of Blackburn and Doncaster roads and called it the town- ship of Doncaster. Subsequent suburban development has overlaid and destroyed the early character of this settlement. (51 Context Pty Ltd et al., City of Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: general report prepared for the City of Doncaster and Templestowe (Melbourne: Context Pty Ltd, 1991), p. 42)

In 1855 Carleton Estate landowner Robert Campbell employed a surveyor, Robert Cooper Bagot, to subdivide the estate allotments into a variety of sizes that would appeal to purchasers with a wide range of land-use requirements. Bagot also laid out a township, which he named Carleton Village. Set where the main road to the Anderson’s Creek gold diggings crossed the Koonung Creek at Kew, this village site included today's Doncaster, Manningham, Williamson, Wilson and Elgar roads, High and Ayr streets, and Whittens Lane, amongst its pattern of roads. (52 Collyer, Doncaster: a short history, (1981; rev. edn Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster- Templestowe Historical Society, c. 1994), p. 8) In the 1850s another group of immigrants, this time from a German- speaking region of Europe (Silesia), arrived in Port Phillip and soon secured small holdings in Doncaster. In time these farmers, who were first described as 'gardeners, established an industry that largely defined much of Manningham s character and purpose for over 100 years. These were the orchardists whose special history is examined in a later chapter.

One such early settler was John Chivers. On 29 June 1840, with his wife Mary Ann and baby son William, Chivers sailed from Plymouth in England on board the Himalaya, arriving in Port Phillip in the September that same year. In his homeland Chivers had built up his own business as a haulage specialist. On the ships register, however, he described himself as an agriculturist'. This apparent change of occupation probably reflects the skills migrants to the Australian colonies were preferred to possess, and which he could claim having grown up on a farm. John Chivers began his working life in the district as a woodcutter for Major Newman, while his wife worked as governess to the Newman children. In April 1842, Chivers squatted on Crown land on the river flats near the end of Fitzsimons Lane. There he cut timber, burnt charcoal and grew crops. He then regularly transported his produce to Melbourne for sale. (38 Poulter, Templestowe: a folk history, p. 6)

In terms of the new settlers' relationships with indigenous people, he proved to be the antithesis of Newman. John Chivers established strong friendships with local Wurundjeri, learning their language and exchanging food and other resources with them. When Mary Ann died in 1850, leaving him with four young children, the local Aboriginal people cared for the older boys, as his descendant Jim Poulter recounts: cMy grandfather Tom and his older brother Willie would go off and play all day with the Aboriginals. After his mother died, Tom spent a lot of time with the tribe going on walkabout - apparently he went to a special ceremony at Mount Macedon and walked all the way when he was only about six or eight. He was treated as one of the tribe and he spoke the language like a native and maintained lifelong friendships' (39 Jim Poulter, interview, 22 June 2001) John Chivers extended his holdings in the district in the 1850s, purchasing acreage first around Porter Street in the vicinity of Church Road.

All the early settlers mentioned above are representative of the many immigrants who, in the earliest days of settlement beyond the environs of the new town of Melbourne, pushed their way into the bush and carved out a space for themselves and their families. Other more entrepreneurial types of the time took advantage of the opening-up of the region in a manner quite different from farming.

Land sales

The Carleton Estate, previously Unwin’s Special Survey, in 1846, after it was subdivided into thirty-two lots by Archibald McLachlan, who leased the land from James Atkinson. The names of the first sub-leaseholders are listed below. Source: Ken Smith, 'Unwin's Special Survey , 1980, p. 13; D1HS

A new Crown grant was issued in Atkinsons name and the land, which Atkinson renamed the Carleton Estate, was subdivided into farms - most of which had water frontages to either the Yarra River or the Koonung Creek. A plan, dated 18 November 1843, of part of the Parish of Bulleen shows lots available for selection varying in size from 640 acres to 1,057 acres. A note written on the plan says that several lots were offered for sale on 20 March 1844 at £1 per acre but that no bids were received.(41 Graham Keogh, The History of Doncaster and Templestowe (Doncaster, Victoria: City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1975), p. 4) Atkinson then leased the land to a property agent, who in turn sublet the lots. Eventually Atkinson sold the Carleton Estate to Robert Campbell in 1851 - the year when Victoria became a colony in its own right and when it was publicly announced that gold had been discovered not far from Melbourne.

Gold glorious gold

The announcement in July 1851 that gold had been discovered at Anderson’s Creek created a rapid but impermanent expansion of settlement into Manningham’s Warrandyte. By August 1851 large numbers of diggers, ill-prepared either for the work or the weather, tramped into the steep, heavily wooded country that Nutt had earlier described as next to impassable’. In the wake of the rush, a small collection of township buildings developed at Bartlett’s Flat above the present site of Warrandyte. (42 Victorian Goldfields Project, ‘Historic Gold Mining Sites in St Andrews Mining Division’, Draft 8/7/99, Cultural Heritage (Department of Natural Resources and the Environment), p. 4) The first wave of diggers did not stay long. An article published in The Argus in December 1851 reported that there were only two men and one gold commissioner now present at Warrandyte. (43 The Argus, 20 December 1851, p. 2, col. 4) The discovery of easier pickings at Ballarat and Bendigo had drawn the diggers away. In 1854 there was a resurgence of interest in the area, and by January 1855, as many as 200 tents had been pitched near Anderson’s Creek. (44 The Argus, 2 January 1855, p. 4, col. 5) This second wave of interest in the region’s gold created another temporary expansion of settlement. By 1856, however, the alluvial workings in the gullies around Warrandyte were all but worked out. Quartz mining continued a little longer but proved difficult work for little return. Many miners moved on, but not all: cSome 100 or so settlers stayed on. They constituted the backbone of the township - and right through till the early 1900s some sixty to 100 miners continued to eke out an existence.’ (45 Murray Houghton, personal communication, June 2001)The villages

Within the last three weeks the towns of Melbourne and Geelong and their large suburbs have been in appearance almost emptied of many classes of their male inhabitants; the streets which for a week or ten days were crowded by drays loading with the outfit for the workings are now seemingly deserted. Not only have the idlers to be found in every community, and day labourers in town and the adjacent country, shopmen, artisans, and mechanics of every description thrown up their employments, and in most cases, leaving their employers and their wives and families to take care of themselves, run off to the workings, but responsible trades men, farmers, clerks of every grade, and not a few of the superior classes have followed; som e unable to withstand the mania and force of the stream, or because they were really disposed to venture time and money on the chance, but others, because they were, as employers of labour, left in the lurch and had no other alternative. Source: Lieutenant Governor La Trobe, 10 October 1851, in Clark, p.6.

Map of the City of Doncaster and Templestowe as it was from 1967 until 1994. (Photo:MCC)

Poster advertising the subdivision and sale of Doncaster Park Estate in 1927. The estate was opposite the East Doncaster School. (Photo: DTHS)

The bakery and post office in James Street, Templestowe. (Photo: DTHS)

Mullens’ blacksmith forge, one of the longest operating blacksmiths in the area. Hillmans’ was another. Mullens’ was built by the local veterinary surgeon at the corner of Andersons and James streets, Templestowe, and purchased by Steven Mullens. It closed in 1980. (Photo: DTHS)

Doncaster township, about 1900. The Shire Hall can be seen in the foreground, Schramm's Common School behind it, and Schramm’s Cottage hidden in the trees. Across the road on the right is the post office. Note the even planting of orchard tree rows in the background and the rows of shelter pines. (Photo: DTHS)

The Doncaster Post Office, built in 1866 opposite the present Council Offices on the site of the Doncaster Central Arcade, photographed around 1907. (Photo: DTHS)

The Doncaster store, operated by the Symons family and then by E. Rolf. (Photo: DTHS)

Kate Schramm stood on her verandah of her house looking over the fruit trees at the panorama of orchards stretching away into the distance. On this warm New Years day everyone was talking about the new century but Kate was thinking of her past in Doncaster. She had lived for half a century in this country and seen many changes in that time. Of course she didn't remember Doncaster in those first years, for she was only a small child, but her earliest memories were of the stringy bark forest that surrounded her home and the small clearing where her father grew vegetables. There were no orchards then, only a few young fruit trees alongside the house. Source: Green, 1987, p.1

Map of the Eight Hour Pioneer Village Settlement, Wonga Park, 1902. Source: Portion of Parish of Warrandyte', reproduced with permission from the Map Collection, State Library of Victoria)

One of the most famous pictures of the main road through Doncaster, taken about 1905. The Church of Christ is on the left, the school on the right and the tower in the centre. (Photo: DTHS)

Forty years after Waldau, the Eight Hours Pioneers Settlement was established in the eastern-most sector of Manningham. Wonga Park, a name attached to a grazing venture on the lower reaches of the Brushy Creek in the 1860s had, by 1889, been taken over by Mutual Life Assurance. Adjoining this land was a timber reserve on which, in 1893, allotments were offered for sale on terms of one shilling per acre for twenty years. A number of the purchasers of lots on this settlement were associated with the Eight Hours Movement, including George Launder, a prominent protagonist, and F. A. Topping, a mason who had worked on Trades Hall. Their names are remembered in Launders Avenue and Toppings Road, Wonga Park, the name by which the Eight Hours Settlement eventually came to be known. (54 G. F. James, Border Country: episodes and recollections of Mooroolbark and Wonga Park ([Lilydale, Victoria]: Shire of Lillydale, 1984), p. 39)

Warrandyte

If there can be such a thing as a watershed moment in the history of the settlement of Manningham, then that moment was World War II. Prior to the war, settlement was of a kind that ensured the rural character of the region was largely maintained. From the 1870s, when the orchards were firmly established, to the start of World War II, settlement patterns in Manningham did not alter greatly. New settlers continued to come into the region but generally took up the rural modes of employment already established in the district. Such was the case for Warrandyte resident David Jenkins’ family. They came to Manningham in the later part of the nineteenth century:

'My father, his parents and brothers and sisters arrived from Wales and took up residence on an 821/2-acre orchard property on New Year’s Day, 1883. I was born on an orchard in Serpells Road in Templestowe in 1931 and have lived in Manningham all my life. I had to stay for my livelihood on the family orchard, which was diagonally opposite what is now The Pines Shopping Centre.' (55 David Jenkins, questionnaire, 30 May 2001.)

Economic depression, which imposed hardship on settlers in the 1840s, struck again in 1892 following the collapse of the land boom, and slowed development in Melbourne and its surrounds for a time. By 1912, however, Melbourne was again experiencing a building boom. As its population approached 700,000, the eastward march of suburbia gathered momentum. (56 Geoffrey Blainey, A History of Camberwell (Melbourne: Jacaranda Press, 1964), p. 66) Then came war.

Jumping Creek Road, Wonga Park, 1940s. (Photo: DTHS)

.

Park Orchards, taken from Granard Street looking east to the Dandenongs in 1926, taken for a sales brochure for the Park Orchards Club. (Photo: D1HS)

A Place in a new country

Rolling hills surround one of the roads built in 1948 for the Scout Jamboree held at Yarra Brae, Wonga Park. (Photo: DIHS)

The majority of the post-war wave of immigrants spoke very little English, some none at all. It is understandable therefore that initially they chose to settle in community groups with others who shared their language, in the inner city suburbs of Melbourne where housing was comparatively cheap. Some, however, looked further out. In the 1950s real estate in the rolling hills of Manningham was also comparatively cheap. Doncaster East resident Jan (John) Verspay came to Australia from the Netherlands in 1954: 'In those days there were too many people in Holland. Things were not that rosy - still recovering from the war. The Australian Government and the Dutch Government subsidised the migrants extensively.' To receive the subsidised fare to Australia potential immigrants had to agree to spend a minimum of two years in Australia. £I arrived in 1954 and spent two days in the Dutch Hostel in Cotham Road, Kew, which was run by the Catholic Migrant Association. Two days later I got a job.' Jan Verspay’s fiancee Hubertha (Bep) joined him in 1956, by which time Jan was work- ing as a landscape gardener: 'We got married in 1957, and we lived for a short while in Mont Albert, and then we moved to an orchard in Vermont. From there on we had bought this land in Devon Drive and Turnstone Street, with unmade roads, no electricity, no water, but it was very cheap in those days.' The Verspays came across their future home site while on a picnic: cIt was nice going for a picnic in the early days. You had your car, you know. In Holland you hadn't been driving a car but here you had your ute. So you'd go for a picnic and you'd see these estate agents sitting along the road, with a beach umbrella, selling the land. This was around 1958. We built the house here, and as far as you looked you couldn't see another house around the place. In the early days people started by putting up a garage and living in the garage. I think you could live in it for a certain time but then you had to be able to move into the house.'

Map of the Park Orchards Estate, 1946. (Reproduced with permission from the Map Collection, State Library of Victoria)

Map of the Parish of Bulleen, including the suburbs of Bulleen, Doncaster, Doncaster East, Donvale, Templestowe and Lower Templestowe (1948). (Photo: DTHS)

Interestingly, between 1966 and 1971 the number of Manningham residents originating from Italy more than doubled. Gus Morello’s story partly explains why. He was born in a little village in Italy called Guadavale. After World War II his father decided to emigrate to Australia: 'He had family here in Australia, an aunty and three cousins. He applied to his aunty to sponsor him to come to Australia. He paid his own fare. He came here in 1950.

His relatives were living on a tobacco farm in Echuca. So he was there for about six months. He decided that, having left his village in Italy, working on the land, that he wasn't going to continue working on the land in Australia - thinking that he was going to Australia for a better life. So he decided to move to Melbourne where he also had some family. From there he got a job with ICI as a process worker. He saved enough deposit to enable us to come here. He took a loan to pay for the full fares, a substantial amount of money too in those days. There was me, my two brothers and my mum. I didn't even know where Australia was. The Italians who migrated to Australia in those years maintained their traditions - their way of life. But in my early years, in my teens, I was focusing more on being an Australian or being part of the Australian way of life. My friends were nearly all Australians.' After working as an architect in Melbourne for a couple of years, Gus decided to travel overseas: 'Before we went overseas, my brother and I had bought some land together in Betton Crescent, Warrandyte. It was three acres. When I came back from overseas and got married, I decided to take over the land and build a house there. I just loved the bush and the undulating hills. I built quite a large house, very earthy, lots of timbers. It was like mountain goat country! It was very steep, but we liked it.' (61 Gus Morello, Suburban Voices oral history project, Whitehorse Manningham Regional Library Corporation, interviewer Lesley Alves, 2001)

The Doncaster East store, known as Dixons in the 1950s. It was built by Sykes in 1910 and was run by Mrs Sykes for several years. (Photo: DTHS)

William Husseys bullock team in Yarra Street. (Photo:WHS)

J. W. Walsh, the Warrandyte baker. (Photo:WHS)

Aggie Moore’s Central Tea Rooms on Yarra Street, part of the garage complex where today’s community centre stands. (Photo: WHS)

The rapid suburban settlement of Manningham from the 1960s has had a major impact on facilities and services. Manningham Councillor Bill Larkin describes that impact: 'Most suburban municipalities develop out from the capital city along a train line or similar corridor. This was not so for Manningham with its unique development around the perimeter at similar times: for example, through Heidelberg to Bulleen; through North Balwyn to Doncaster; through Blackburn to Doncaster East; through Nunawading to Donvale; and then the unique townships of Warrandyte, Park Orchards and more recently, Wonga Park. The impact of simultaneous developing around the perimeter created the need for many facilities and services to be provided across the municipality at the same time - road construction, schools, kindergartens, sporting facilities. This required a huge financial input from a young, growing municipality where mortgages limited cash flows for residents and Council had demands growing faster than the rate base. For example, whilst the 1960s saw many of the clay private streets constructed (at a cost to residents) it was not until the 1980s that roads like Tunstall, Beverley, Leeds, Wetherby and many others were constructed. Roads like Thompsons Road North, Templestowe Road, Blackburn Road North and Springvale Road North are still not much more than country lanes. Today we are still playing catch-ups' with those financial demands of the early suburban settlement with the need to add some refinements to our environment - continuing the development of Ruffey Lake Park; the construction of a function centre to meet community requirements like debutante balls, sporting presentations, schools celebrations. A new municipality today provides many of these refinements from day one, and the community expects and demands that they be provided. The perimeter manner in which Manningham was settled as suburbs in the 1960s, '70s and '80s placed emphasis on practical essentials. It is only in recent years that these refinements are able to take place.' (66 Bill Larkin, personal communication, 19 June 2001)

A citizenship ceremony held on 7 May 1976 (Photo: Irvine Green; Doncaster/Templestowe Album, MCC)

These stories from recent settlers almost echo the pleasure and optimism that Penelope Selby articulated in her letters home to England in 1841. All of the settlers from 1835 to the present, who chose to live in the municipality, have contributed to making Manningham the city it is today - a city of infinite variety, richly diverse.

Did someone say ... ‘Huh! Most of them are more white than black? This may be true in terms of ancestry for some, but it must be recognised and accepted that the percentage of Aboriginal blood is completely irrelevant. If you have any Aboriginal ancestry, identify as an Aboriginal person, and are accepted as such by the Aboriginal community, then you are an Aborigine. Source: Koorie, p. 5, presented in conjunction with the exhibition 'Koorie', displayed in Kershaw Hall of the Museum of Victoria.

And what of the first people - the Wurundjeri? Several generations of Wurundjeri families were born and lived at Coranderrk until its closure in 1924. During that time it was difficult for them to stay in regular contact with that part of their custodial land which lay within present-day Manningham. Some were able to maintain at least a tenuous physical link with the area: Thomas Chivers and his tribal brother' Billy, for example, visited each other throughout their lives, with Billy visiting the Chivers' home in Templestowe as late as the 1920s, walking (or possibly riding) all the way from Healesville despite being around 80 years old. (68 Jim Poulter, interview, 22 June 2001. See also Lee Scott-Virtue, 'Aboriginal History of Warrandyte', part 4, Warrandyte Historical Society Newsletter, no. 27, October 1982, p. 3) For others, a more general connection with their land was maintained through passing on its stories to those no longer able to spend time there.

During its lifetime, Coranderrk eventually became home to many surviving Kulin people. They made accommodation to the dominant European culture in a range of ways - from marrying Europeans to participating in the broader economy and in national events. Martha Nicholson, who was born at Coranderrk in 1914 and is a direct descendant of William Barak, remembers seeing as a child an elderly Aboriginal man who would sell boomerangs on the main Healesville Road. (69 Vicki Nicholson, personal communication, 5 July 2001) At least three residents - David Mullett, John Rowan and George Terrick - served as soldiers during the Great War. (70 M. H. Fels, Some Aspects of the History of Coranderrk Station (Melbourne: Aboriginal Affairs Victoria, c. 1999), p. 52) With the closure of Coranderrk, some families moved away from the area for a time. To many outside observers, little Wurundjeri connection with the land remained. One of the many tragic aspects of life on reserves such as Coranderrk had been that people were restricted in handing down cultural knowledge to younger generations, with the effect that some was lost forever. Other knowledge, however, was carefully passed on, and more recent generations have begun to piece it together and to reassert their continuing links with the area.

In the 1970s and 1980s Wurundjeri families were able to enhance their connection with their traditional custodial areas, including that now encompassed by Manningham. This was a time when momentum had begun to build in the broader Australian community towards recognising self-determination for Aboriginal people, and local cultural and political organisations were formed. The Wurundjeri Tribal Land Compensation and Cultural Heritage Council, which was registered in 1985, has been one of several organisations through which Wurundjeri people have consulted about sites of significance in the area. They have helped to protect these sites; they have also educated the wider community about them. In turn, local councils responded to growing interest in indigenous matters with a range of educational events and studies, and developed policies recognising the indigenous communi- ty’s historical significance as well as its contributions and future needs. It has become easier, for example, for Wurundjeri to access some traditionally important sites now occupied by parklands.

In recent years, cultural officers and other senior representatives of the Wurundjeri community have shared aspects of their Aboriginal heritage with the community by working with local groups such as schools as well as government bodies such as Parks Victoria. A series of festivals on significant Wurundjeri sites, including the Bolin Bolin Billabong and Westerfolds Park, have provided opportunities to build rapport and understanding. Activities offered might include anything from dances to camping overnight in traditional style. Some of the festivals held at Tikalara Park, for example, have attracted more than 3,000 people. (71 Patrick Fricker, personal communication, 17 July 2001) This process has involved a sharing of knowledge between Wurundjeri and other members of the community, which in turn has led in the past few years to a mushrooming of interest in working together and learning from each other.