Orchards

In plucking the fruit of memory, one runs the risk of spoiling its bloom. Joseph Conrad. The arrow of gold. 1925

Friedensruh on the Thiele family property, covered with vast orchard plantings. (Photo: DTHS)

For decades in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the orchardists of Manningham largely defined the district’s character and purpose: 'People used to come out to Doncaster in the springtime just to see the blossoms. They’d drive up what is now Doncaster Road and there would be just the odd house, but on either side of the road there’d be blossoms. It used to be a picture in the springtime. It was always a lovely place to go and see all the blossoms. It was known - 'Were going out to Doncaster to see the blossoms'. (1 Olive Crouch-Napier, interview, 5 June 2001). Driving up Doncaster Road today, little that is immediately obvious to the eye remains of that area’s early fruit-farming era, but orcharding has not entirely disappeared from the landscape of Manningham. An orchard belonging to the Aumann family is still in operation in Tindals Road, Warrandyte. Over the past 140 years, five generations of Aumanns have worked in the district’s fruit-growing industry, but changes imposed subsequent to the spread of suburbia have greatly impinged on their ability to operate effectively Further out in Wonga Park only one orchard continues to operate - the Couper’s orchard on Jamieson Road, which was developed on land once occupied by a member of the pioneering Read family. (2 Context Pty Ltd et al, Wonga Park Heritage Study Report on Stages 1 and 2 (Manningham, Victoria: City of Manningham), 1997, n.p.). The Colella orchard, also in Wonga Park, had been worked since 1966 by Ralph Colella and John Buceto. Consisting of about 7,000 apple, peach and pear trees, this orchard recently had its final harvest. (3 Manningham Leader, 9 May 2001, p. 8). Pettys 'demonstration orchard’ stands in Templestowe as a reminder of the areas past. The managers of the orchard hold a festival annually to promote the many historic varieties of apple produced there in the interest of preserving diversity. The disappearance of orchards in the area, combined with the rise of self-service supermarkets in the 1960s, meant that many different varieties of fruit developed by local orchardists for a different era of retail ing were in danger of being lost. Peter Adams, a descendant of the Adams orcharding family of Warrandyte, details local efforts to preserve variety: 'Varieties of fruit, which our family listed, have disappeared with the advent of recent varieties that store and present attractively in supermarkets and that can be handled by the consumer. People decided no longer to trust their fruiterer with selecting. They wanted to choose the fruit and as soon as that happened, we had to have non-bruising fruit, picked greener, often cool-stored for a significant period. The older varieties didn’t store well, or didn’t keep very long on a shelf or in a supermarket; they were discarded and ripped out of orchards completely and replaced with imported varieties. We realised that in peaches, some of the older varieties were superb eating and should be conserved. We may even see a return for a boutique market. Robin Morrison and I have collected forty of the Doncaster-Templestowe varieties. Other families have been involved in collecting heritage apples and pears.’ (4 Peter Adams, interview, 16 May 2001)

Fred Gedye in the foreground enjoys the fruits of the orchardists labours. (Photo: DTHS)

In Wonga Park the Upton family orchard, purchased by Arthur J. Upton in 1921, ceased operating around 1998. Cool stores at the rear of the house were removed in the mid-1990s and by 1997 the property was undergoing subdivision. (6 Context, Wonga Park Heritage Study, n.p.). A Tully orchard in Victoria Street, Doncaster, with the remains of its former pine-tree windbreak standing on the south side, was recently bulldozed and a retirement village is being established there. Another orchard at 180 Williamsons Road, Doncaster, still actively being farmed by the Morrison-Crouch family in the early 1990s, is now subdivided and mostly built on. (7 Context Pty Ltd et al., City of Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: general report prepared for the City of Doncaster and Templestowe (Melbourne: Context Pty Ltd, 1991), p. 66; updated information courtesy Eric Collyer, personal communication, 4 June 2001)

Windbreaks

Perhaps the most obvious legacy of the orchardists is the vista of pine and cypress trees that stand tall along many of the ridges of Manningham’s hilly countryside. Some were planted as windbreaks over a century ago and delineate the former perimeters of fruit-tree blocks. Manningham largely owes this living reminder of its orcharding heritage to Doncaster’s German-speaking settlers of the nineteenth century. Their origins linked them with one of early Victoria’s most important and influential botanists - Baron Ferdinand von Mueller, the first director of Melbourne’s famed Botanic Gardens. In the nineteenth century, when the orchardists first came into Manningham to farm, few were experienced fruit growers and none knew anything of the climatic vagaries of the region in which they had settled. Over time they indiscriminately cleared their farming lands of native bush to create more acreage for planting, but in so doing exposed delicate young crops to the wind-driven extremes of the southern colony’s seasons - searing, hot north winds in summer, biting, cold southerlies in winter. Botanic Garden records show that the Waldau Lutheran Church in Doncaster received plants from Mueller in 1862 and later years but the actual species are not identified'. (8 Francine Gilfedder & Associates, The Future Management of Pine & Cypress Trees in the City of Manningham (report prepared for the Environmental Planning Division, Manningham City Council, 1996), p. 10). In 1890, however, on a return trip to Germany, John Finger collected and brought back to Manningham seeds of the Pinus insignis (later renamed Pinus radiata) variety of pine tree. Many of the pine trees grown from these seeds still stand in the environs of Rieschiecks Reserve. (9 Irvine Green, The Orchards of Doncaster and Templestowe (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, 1982), p. 27)

Pine trees remnant from the orcharding landscape, along the path to the end of Mandella Street, Templestowe, 1977. (Photo: Kay Mack)

What's in a name ?

If the pine trees serve as a visual stimulus for remembering the region’s orcharding history, then street names contribute aurally. Whenever residents of Manningham give their home address as, for example, Beavis or McGahy Court, Templestowe, or Speers Court or Leber Street, Warrandyte, or Ireland Avenue, Doncaster East or Kent Court, Bulleen, they inadvertently pay homage to pioneer fruit growers. In his 1985 booklet, The Orchards of Doncaster and Templestowe, local historian Irvine Green identified forty-four sites in the region where, by the 1870s, fruit-growers had established orchards. Of the families named by Green, no fewer than thirty-four have been honoured in the naming of local streets.

Some fruit varieties also carry the names of pioneer orchardists. In 1893 Fred Thiele came up with a yellow-fleshed cling variety of peach which he named the Thiele’s Cling. Three years later August Zerbe produced the highly coloured, white-fleshed Zerbe peach. Peach varieties developed by Doncaster-Templestowe orchardists include: Hudson’s Catherine Anne variety (1900); Smith’s mid-season, white-fleshed peach (1900); Whitten’s Palmerston peach, a yellow-fleshed, late season variety (1900); and Anzac, Beale Noonan, Millicent and Wagner. These are just a few of the many which collectively became widely known as 'Doncaster Varieties' and were grown in orchards throughout Australia. (10 Green, The Orchards of Doncaster and Templestowe, pp. 52-3)

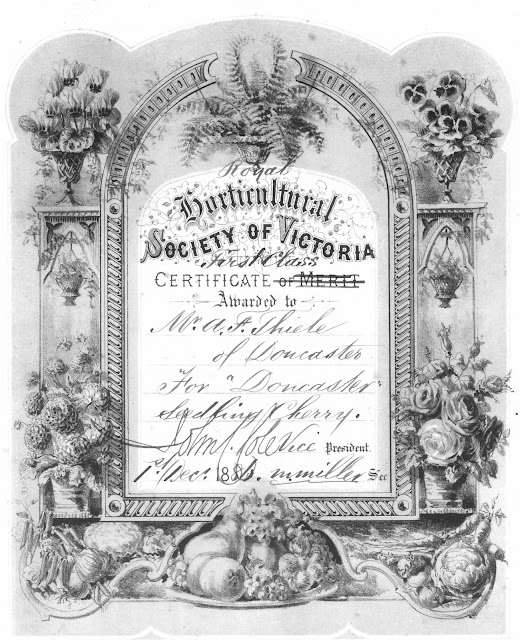

Frederick Thieles certificate for first class ‘Doncaster seedling cherries, awarded by the Royal Horticultural Society of Victoria in 1886 . (Illustration: Eric Collyer)

It was a large scheme with eighty orchard blocks on the slopes of the Park. Rows of pine trees were planted and some areas of bush land left as wind breaks. Ten dams were scooped out to supply water for the young fruit trees during the hot summer weather and near the group of houses a bore was sunk and a windmill erected. In the north-east corner a fifteen-acre paddock was fenced off for the many horses required to work the orchards. (11 Irvine Green and Beatty Beavis, Park Orchards: a short history (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, 1983), p. 6)

Tom Petty, who presided over an empire of some thirty orchards in the district. (Photo: DTHS)

Orchards dominate the landscape as far as the eye can see in 1907. Tom Petty’s house, Bayview built by Alfred Hummel is in the foreground. Whittens Lane crosses the picture in the background. (Photo: DTHS)

Buildings

Buildings erected by orchardists also serve as reminders of Manninghams orcharding past. A heritage study of the City of Doncaster and Templestowe, published by the Council in 1991, identified over forty-five buildings in the district as being of significance with regard to their connections with Manninghams orcharding history. (14 See Context Pty Ltd, City of Doncaster Heritage Study. See also Richard Peterson, Heritage Study: Additional Sites, Recommendations, (City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1993); Carlotta Kellaway, Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: Additional Historical Research (City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1994); Context, Wonga Park Heritage Study). Some have since been demolished and suburbia has so dramatically encroached on the others that a concerted effort is needed, in some cases, to seek them out. The Clay house at 1 0 Dehnert Street, Doncaster East, is one example. Once situated on 21 acres of orchard land, the house is now completely surround ed by suburban housing. The same applies to an orcharding homestead at 23 Hemingway Avenue, Templestowe. The property was originally owned by Richard Serpell, one of the pioneer orchardists of Templestowe, but has been held by members of the Jenkins family for the last 110 years. (15 Carlotta Kellaway, Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: Additional Historical Research (City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1994); Context, Wonga Park Heritage Study, pp. 16, 24). ‘Ownership of the 1 2 2 1/i acres was held in the Jenkins family until 40 acres were sold in 1969 and 8 2 1/2 acres in 1977. The reason for the sale was encroaching suburbia and resultant rising rates. (16 David Jenkins, questionnaire, 30 May 2001)Suburbia has also risen close behind two houses still standing in Warrandyte Road that were the homes of Warrandyte orchardists George and Frank Adams. Georges house at 298 Warrandyte Road was built around 1918-19. His brother Franks house was started soon after in 1919-20. (17 Carlotta Kellaway, Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: Additional Historical Research (City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1994); Context, Wonga Park Heritage Study, p. 66). The brothers moved to their new homes upon marrying but both had been farming the land since 1910. Franks grandson Peter Adams has traced details of his family’s early history: 'My grandfather’s father came from Berkshire in England. They settled in Templestowe in the late 1880s. After working for other people in Doncaster and Templestowe, my grandfather and his brother travelled out to Warrandyte around 1910 to clear their block of land and to begin an orchard there. In the early days, the soil was so poor at Warrandyte that it wasn’t deep enough to grow fruit trees and my grandfather and his brother started by growing crops such as potatoes, peas and beans and marketing these for income to keep themselves supported while they built up the soil. They brought in manure, straw, and often soil from the nearby Deep Creek and carried off loads and loads of stones. (18 Peter Adams, interview, 16 May 2001)

Not all descendants of early orchardists carry family memories through the generations. John Beanland emigrated from Yorkshire in 1853. His wife Mary and their eight children followed in 1858, and the family became the first resident owners of their land in Church Road, Doncaster, in 1861: ‘Two sons, Thomas Seaton and John Griffith Beanland, quarried stone from the property for buildings (including Schramm's Cottage and Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Doncaster) and were the first to plant fruit trees on it. How did we become aware of this? In 1950, Graham Beanland, great-great-grandson of John and Mary and at the time a young university student, was living in nearby Box Hill and sought vacation employment on a Doncaster orchard. Miss Affleck, the postmistress at Doncaster, arranged this with Everard Thiele, who owned a very large and diverse orchard property in Church Road. After verifying his new employees name, Everard said that he had checked his records and found that his property had been bought from Beanlands by his father! What a coincidence - none of the family had any knowledge of a Doncaster property being owned by their forebears'. Source: Graham Beanland, personal communication, 6 July 2001.

In Waldau Court, Doncaster, past and present are juxtaposed in a way that permits reflection on how the site may have looked when only the pioneering Thiele family of orchardists lived there. Dwellings fairly typical of homes built in Doncaster in the last quarter of the twentieth century stand on one side of the court all the way up to the driveway of Friedensruh, built in 1853 for pioneer orchardist Gottlieb Thiele and clearly a house from a different era. (19 Two German words - Friede meaning peace’ and Ruhe meaning ‘rest’ - are the inspiration behind the name of the house. See Eric Collyer and David Thiele, The Thiele Family of Doncaster: a history of Johann Gottlieb Thiele and Johann Gottfried Thiele and their descendants, 1849-1989 (Doncaster, Victoria: Thiele Family Reunion Committee, c. 1988), p. 56). It is still possible to stand at the gate of Friedensruh, gaze across the open space that is now Ruffey Lake Park and imagine the area filled with rows of fruit trees. The orchard surrounding Friedensruh was purchased by the Shire of Doncaster and Templestowe in 1966. The house continues to be owned and occupied by members of the Thiele family. Eric Collyer, great-grandson of Gottlieb and Phillipine Thiele explains: 'The homestead is still owned by family descendants today. The Council had purchased the property from the Thiele family in 1976 and put tenants in as caretakers for a few years. For various reasons they decided to sell the property, and in 1981 it came back to family ownership again.' Descendants of the Thiele family remember Friedensruh as a centre of hospitality: In my childhood years scarcely a Saturday went by without visitors to Friedensruh for afternoon tea. I remember my grandmother’s brother and sisters in particular as regular visitors. The large table in the dining room would be filled with plates of homemade sandwiches, cakes and biscuits, including the ever-popular streusel kuchen - a traditional German cake.' (20 Eric Collyer, interview, 12 June 2001). In 1978 the Australian Heritage Commission listed the house and outbuildings of Friedensruh on the Register of the National Estate. (21 Register of the National Estate, file number 2/15/017/0001). As far as I know it’s one of the few intact complex of buildings - meaning the house and associated outbuildings - that’s still extant from the early fruit-growing era.' (22 Eric Collyer, interview, 12 June 2001)

Picking fruit on Alfred Thieles orchard, about 1920. Alfred is second from the left. (Photo: Eric Collyer)

Previously there existed a strong local infrastructure, with many businesses pro viding support and supplies to the orcharding industry: ‘In the past, the Aumann Family Orchard has been state of the art in its operations; that is simply no longer possible. We are restricted by our increasingly suburban location/ Once, when produce was transported solely by horse and cart, the orchards proximity to the main market was a notable advantage. As Barry Aumman points out, basic orcharding practices appear now to be incompatible with encroaching suburbia: ‘Operations of this type, in this area, cannot indefinitely exist. However, current planning objectives ensure that we are unable to relocate, as other orcharding families have succeeded in doing. The planning restrictions that do not encourage innovative use of our land restrict us even further/ The orchard is further limited by its relatively small size: ‘Economies of scale mean that orchards now need to be much larger, and their trees planted on flatter landscapes with easier access to cheap irrigation water. As with so many businesses, profit margins are only a fraction of what they used to be. In the past people in this district were able to make a good living from an orchard of 15 or less acres. Today, many orchards are in excess of 200 acres in size, thereby producing enough volume to supply the export and interstate markets, as well as the supermarkets. Other changes include a reduction in the number of small, independent fruit shops in Victoria - orchards like ours were geared towards supplying them. Supermarkets now possess a much greater market share and only deal with the larger suppliers/ The competing wishes of those who have recently moved into the area but would like to see no further change to the local environment have led to feelings of frustration for people like Barry Aumann: ‘Like any other business, we need the opportunity to expand, to develop, to relocate and to build on the expertise gained over several generations. I feel like a stranger in the area where I have lived and worked for most of my life. There are so few of us now making an income from the land here - we feel like a minority group. Source: Barry Aumann, questionnaire, 27 June 2001, and personal communication 8 August 2001.

The fruit of memory

Although much that visually signified the orcharding era has gone from the landscape, images and experiences of the last years remain in living memory Templestowe resident Garth Kendall remembers how the region once looked: 'We owned two blocks of land back to back in 1953. In 1954 we built our house. There weren't too many houses in the street. We used to go to the little Catholic Church up on the hill in Atkinson Street. It was quite fascinating - up high, all you could see for miles were orchards. I worked in Fawkner, and had done since 1954, and the journey to work and back used to be through wide-open spaces. Late at night you'd run into ground fog.' (23 Garth Kendall, personal communication, 12 February 2001)

Transporting a load of pears from Gedye’s orchard in Doncaster. (Photo: DTHS)

Most orcharding children participated in the work of the orchards: 'One of the most responsible jobs with the hammer and nail was to repair the sides of broken boxes which were used to transport fruit to the Victoria Market. We became experts at sawing, cutting, nailing and repairing boxes so that there was no delay with the packing and marketing because the fruit was picked close to ripeness in those days and had to be transported immediately. '

Fruit-packing box label for Tower Brand export pears. The export trade was very lucrative, outstripping the local market for many years before being curtailed by the advent of the European Common Market in 1958. (Eric Collyer)

It was usually eaten within a day or two of harvesting.' (25 Peter Adams, interview, 16 May 2001). Ian Morrison remembers being allowed occasionally to stay home from school when it was picking time: 4 can remember staying home from school to pick pears when I was fourteen or so. We were very busy in the summer time. With the peaches it was January - it was a busy month, and into February we'd be busy with pears. We picked those through to March. I can remember the packing days. They had wrapping paper for the pears, a sort of tissue paper, and then my brother would take them in the wagon across to the Box Hill Station and stack them there. Then they'd go by rail to Sydney. They used to send a lot of pears to Sydney in the 1920s.' (26 Ian Morrison, interview, 31 May 2001)

Participants in a tree-pruning competition, early 1900s: from left, J. Whitten, Harry Reynolds, August Zerbe, Harry Brown (back), Will Petty, Jim Rhodes (on ladder), Harry Clay (front), Fred Morrison (back with pipe), Frank Petty (sitting on ladder), Thomas Petty (back), Harry Stone, Bill Duncan, John Finger, Bill Elder (front), Frank R. Petty (obscured at back by branches), Jack Plumb, John J. Tully, Will Webb (front), Herb Clay (at front with long handled tool), Bert Petty (in tree), John Tully, Fred Petty (next to Tully), Alf Smith, Ed Petty, Alf Chivers, George Watson, Ted Street, Alf Bloom (sitting on ladder) and Henry Petty. Photo: Ian Morrison, copied from the original collection taken by Ernest Thiele, Henry Thiele and Dan Harvey

The beginnings

The patriarchs and matriarchs of Manningham's pioneering orcharding families had come, in the middle of the nineteenth century, from faraway places in the old world' to an even older world where they hoped to forge a new life. We could try to detail each story of the origins of these pioneers because so many of their descendants still live in the district; but it would soon become apparent that the major themes of each family’s story are remarkably similar. We have therefore focused on those families who have already undertaken the painstaking and time-consuming research required for writing a family history. (27 To Eric Collyer and David Thiele, and to Eric Uebergang, we are greatly indebted for the historical details of the German pioneers who settled Waldau in Doncaster. We are thankful, too, to Hazel and Jim Poulter for recalling, collecting and publishing the folk history of their forebears who were among the earliest settlers of Templestowe). Whatever drove the earliest European settlers to seek a new life far from their homelands - be it war, religious persecution, economic hardship, or just an individual sense of adventure and opportunity - it was Manningham's gain, for so many of them worked hard, in unfamiliar and adverse conditions, and built a legacy that greatly benefited a new colony and state. The main places of origin of Manningham's pioneer orchardists were Europe and Great Britain.One of the busiest and most successful of the first gardeners, Henry Crouch, had to build his house at night because he couldn’t afford the time during the day. His son Henry held a lamp for him to work by. Needless to say, the boy kept going to sleep... Source: Green, 1985, p. 17.

The British

Fruit-packing boxes at the orchard shed in Tuckers Road near King Street, Templestowe, 1974. (Photo: Garth Kendall)

Felloe: the outer rim or a part of the rim of a wheel, supported by the spokes; each of the curved pieces which join together to form a wheel rim. Source: Oxford English Dictionary.

The Germans

Committee, 1993, p. 12)

Silesia is a region in Eastern Europe, lying in the upper O der basin and bordered in the South by the Sudeten Mountains. It was originally an old Polish province, which, during various stages of its history, had endured Bohemian, Magyar, Austrian and Prussian rule until it was restored to Poland in 1945. Sadly, the term ‘Silesia has, strictly speaking, becom e nothing m ore than a m odern geographical expression since the territory was, for the m ost part, absorbed into the frontiers of Poland once more. Source: Collyer and Thiele, p. 8.

Ten years later, Melbourne businessman William Westgarth, impressed by the generally hard-working, pious and abstemious character of the South Australian Lutheran community, actively promoted the migration, this time to Victoria, of other discontented Germans from Silesia. (33 Uebergang, Eric. Carl Samuel Aumann: the family history 1853-1993. Aumann Reunion Committee, 1993, p. 14). Still nervous about religious intolerance, these Lutherans had the added incentive of Prussia’s rising militarism to leave their homeland. Uncertain about the prospect of being conscripted into the military, the Germans saw Westgarth’s proposal as their chance for freedom. He devised a bounty scheme whereby he received a promise from the Colonial Secretary of £5 per person for assisted passage to Australia for the first 200 to migrate, provided their back- grounds were in agriculture. Agents in Prussia of dubious integrity exploited this scheme, and many of the Germans found, upon arriving in Australia, that they were not eligible for the bounty because they were not agricultural labourers. It made for some a bitter start in the new country, but one which, with hard work, they eventually overcame. (34 Eric Collyer and David Thiele, The Thiele Family of Doncaster: a history of Johann Gottlieb Thiele and Johann Gottfried Thiele and their descendants, 1849-1989 (Doncaster, Victoria: Thiele Family Reunion Committee, c. 1988), pp. 15-17). Gottlieb Thiele was one such immigrant. Credit is generally given (with some reservations) to Gottlieb Thiele for encouraging many Germans to settle in Doncaster. Thiele began as a tailor in Melbourne but ill-health caused him to consider the value of country air. Gottlieb Thiele, it is generally believed, was the first settler in Doncaster to start an orchard large enough to provide a supply of fruit greater than what was needed by the immediate family. He began in 1853 by planting 3 acres with fruit trees. (35 Uebergang, Eric. Carl Samuel Aumann: the family history 1853-1993. Aumann Reunion Committee, 1993, p. 29)

Heimat, a Lutheran cottage in George Street, Doncaster. (Photo: DTHS)

Consolidation and invention

From small clearings in the bush, orchards spread across the land till, in the first years of this [20th] century, Doncaster Templestowe had developed a characteristic appearance. Straight lines of pine trees planted as wind breaks bordered the blocks of orchard trees and in corners, dams, like jewels, dotted the countryside. Source: Green, 1985, p. 5.

Few of the earliest orchardists came into the district with a view to growing fruit. Most began by planting vegetables, perhaps some vines, and a few fruit trees to provide mainly for their family’s needs. The early days were a time of trial and error but in time the settlers began to identify which crops best suited the land they had settled on. Acreage initially devoted to market garden crops was gradually reduced while at the same the time acreage devoted to fruit trees increased. Within a decade in the 1880s, 274 acres given over to market gardening were reduced to 100 acres while the 300 acres dedicated to fruit trees rapidly expanded to 1,500 acres. (36 Green, The orchards of Doncaster and Templestowe, p. 15). Although not amongst the earliest settlers in the district, Ian Morrisons parents nevertheless made their start in orcharding around 1900 in a similar manner: 'My Dad bought land down in Wilsons Road. He planted some of it with fruit trees but fruit trees take years to come into bearing, so he also planted strawberries. Mum and Dad made their start by growing strawberries. As the fruit trees came into bearing, they gradually went out of strawberries and relied on the other fruit. They had peaches, plums, pears, a few apples, and then later on lemons and figs.' (37 Ian Morrison, interview, 31 May 2001)

Success brought expansion, which in turn exaggerated problems. Commercial success depended on an abundant, unspoiled supply of fruit. Having to deal with problems of pest infestation and water supply encouraged inventiveness amongst the second generation of orchardists who built on the hard work of their pioneering parents. Solving the problems of spraying for pests on a large scale led, in time and through various ingenious forerunners, to the invention of the 'Bave-U Motor Spray Pump'. In 1908, at the suggestion of Tom Petty, Jack Russell designed and built the motorised orchard sprayer at his engineering works in Box Hill: 'Russell was originally a motor mechanic and a bit of an engineer.' (38 Ian Morrison, interview, 31 May 2001). Bay View was the name of Petty’s house in Doncaster. In time, hundreds of these machines came to be used on orchards throughout the district and beyond because of their reliability and efficiency

In 1897 an interstate conference on fruit growing was held; as a result, a uniform size for fruit cases was agreed upon 20' x 15' x 10'. Source: Green, 1985, p. 25.

Perhaps because of their shared endeavour, fruit growers of the district developed a strong sense of community and freely exchanged ideas and experiences in the interests of improving yield. This was formalised in 1892 when a number of fruit growers met at the Athenaeum Hall in Doncaster and formed the Doncaster Fruitgrowers Association. Frederick Thiele was elected the Association’s first president. Fred, as he was always known, was the sixth child of Gottlieb and Phillipine Thiele. One of the aims of this Association was to educate fruit growers about the latest best practices, which could only serve to improve the general condition of all the fruit growers' crops. Lectures and demonstrations were organised on tree culture, packing and orchard management, and on the control of pests. Uniformity of the size of fruit-packing cases was agreed when more of these associations formed in other fruit- growing districts, and uniform pest-control regulations were also eventually introduced. (39 Green, The Orchards of Doncaster and Templestowe, p. 25)

Water, of course, was a vital component to the success of the orchardists' crops. In the earliest years the fruit growers carried water in buckets up to the young trees from natural waterways. But as production grew, and with the inevitable cyclical advent of a dry season, the provision of a more accessible and reliable water supply became paramount. After a particularly dry season in the 1890s, dams began to appear on properties throughout the district. Ian Morrison believes his father had more dams on his property than the average orchardist: 'Before my time, my father built a dam up at the top of the hill and another one down in the gully and actually he put it near the creek. His idea was to pump water out of the Koonung Creek up to this dam and then water his orchard from that. He spent a fair bit of money on it but the top dam was a failure because it wouldn't water, but the second dam, he pumped a lot up into that and then he could water the lemons and the fruit that was lower down. He liked building dams.' (40 Ian Morrison, interview, 31 May 2001)

Mixing Bordeaux spray, a fungicide made from lime and copper sulphate, used for curly leaf and black spot. (Photo: Ion Morrison, copied from the original collection taken by Ernest Thiele, Henry Thiele and Dan Harvey)

Russell’s ‘Bave-U’orchard sprayer. (Photo: Irvine Green; copy: Eric Collyer)

It was very hard. A lot of work involved. The job required a lot of machinery and I can remember ploughing row after row in the hot sun. It was very hard work, and getting up at 2 a. m. to go to market to try to sell the fruit; lot of improvising, had to make do with what we had. Still had time for fun. You could do a certain amount of work and then had to have a break; we had some fantastic water and peach fights. Source: informal interview with Mr Beavis, Park Orchards, cited in Bateson, Vidovic and Walker, Appendix 4.

A motor-operated spray pump used in the orchards, 1906. (Photo: DTHS)

Ploughing was an integral part of the cycle of work undertaken on orchards. In the earliest years the ground between the rows of trees was turned over by a horse-drawn plough, but low branches on the trees meant the horse could not get close enough for the soil beneath the tree to be ploughed. The ground close to the tree trunks was cultivated using spade and hoe. An early design of a plough tried to overcome this problem by having the handles and the hitch bar offset to one side. This permitted the horse to walk clear of the fruit trees while the ploughman guided the implement under the trees.43 Ploughing was always laborious work. £We mostly did it about twice a year. In the autumn we'd plough the furrows up towards the tree and we'd leave a good centre furrow for rain in the winter. Then in about September or October, we'd plough away from the tree. We used to have a shifting handle, mouldboard plough and we used to have to wind it in and out between the trees. Then the Petty brothers invented a plough.'44

A restored three-furrow mouldboard plough (1942), designed and manufactured by Daniel Harvey It was originally a twofurrow plough pulled by horses. The third furrow was added for use behind a tractor. (Photo: Peter Adams)

A Petty plough with three serrated discs, manufactured by Daniel Harvey Its original colour was deep red. (Photo: Peter Adams)

The Petty Plough, designed in the first place by brothers Frank and Herb Petty in 1932, and manufactured for many years by Daniel Harvey at a nearby foundry (site of the present-day Box Hill Library), was widely used on local orchards and beyond.45 Ian Morrison remembers that the Petty Plough made a big difference: £It was on wheels and it was a disc plough. You steered it with two handles and you just steered your way in and out of the trees and it would take the furrows right out. It made it a lot easier.'46

Dan Harveys great nephew Peter Adams, ploughing off’outside the caretaker’s cottage of the Athenaeum Hall. (Photo: Ian Morrison, copied from the original collection taken by Ernest Thiele, Henry Thiele and Dan Harvey)

Poem: Daniel Harvey, Box Hill 1876 1969 There was a foundry that bellowed and thumped and thundered smoke and melted iron that fired the face of Daniel Harvey. He moulded ploughs to turn the sods and form the rows of orchards that yielded fruits, crammed a market and fed the folk of Melbourne. They built the suburbs that spread out far and took the place of orchards, they shed the rows and smoothed the sods that rusted ploughs and killed the foundry. A writers place now fills the space that once was box and is the hill of Daniel Harvey. There is a library that holds a shelf which has a space that still awaits the history of Daniel Harvey. Peter Adams.

The cool stores

Once their orchards were established, the orchardists extended the fruiting season by judiciously planting a range of early to late maturing varieties: £You needed a mixture of fruits and a long period of harvesting for the maximum chance of income from late November through to March. So, we grew in sequence: cherries followed by peaches, plums, apricots mid-season, and then apples and pears in the late season. My family also grew a number of other fruits in small quantities such as quinces, loquats, oranges and nectarines/47 But the income-producing season only prevailed as the fruit ripened on the tree. Prolonging the storage period could extend the supply of fresh fruit for the markets. Initially this meant that as the daily harvest proceeded, the storage cases in which fruit was carefully packed were kept in the cool shade of the pine trees. Then, at the end of the day, the cases would be stored in the most naturally cool space available. Sometimes this was just a corner of a barn. Sometimes the cases were placed in a cleverly ventilated cellar: 90Templestowe Cool Store built in 1922, on the corner of Porter Street and Fitzsimons Lane. The picture, taken about 1930, shows fruit growers and their transports. (Photo: DTHS)

Opening of the Central Government Coolstore Extension. The original buildings date from 1903. (Photo: Ian Morrison, copied from the original collection taken by Ernest Thiele, Henry Thiele and Dan Harvey)

Frederick Thiele kept his cellar cool and well ventilated with cool air from the surface of [a nearby] dam; large-diameter pipes led from the edge of the dam into the cellar. High flues above the cellar created a draft that caused suction to drag the cool air along the pipes.48

With the development of forms of refrigeration in the late nineteenth and early twenti- eth centuries, however, the opportunities to extend storage time expanded considerably: cWhen cool storing came in apples and pears had a market through the winter months'.49

Sorting fruit at Keith Petty’s Coolstore, about I960. (Photo: Ian Morrison, copied from the original collection taken by Ernest Thiele, Henry Thiele and Dan Harvey)

Templestowe Cool Stores superb timber interior, January 1973. (Photo: Garth Kendall)

But bumper times were upon the orchardists, so within four years of its opening, the Government Cool Store had to be extended twice in order to try and meet local demand for storage space. And this was in spite of the fact that many fruit growers started forming co- operatives to build community cool stores in the interim.52 In 1911, for example, local grow- ers built the West Doncaster Co-operative Cool Store at the corner of Doncaster Road and Beaconsfield Street.53 Olive Crouch-Napier recalls her childhood impressions of the cool store: £I remember they had big trolleys and the cases of fruit would be put on the big trolleys and would be wheeled in and they had their allotted place where they kept apples or whatev- er until there was a better price at the market perhaps. It would be so cold for kids. Our noses and our hands would get so cold we'd have to go outside even in the colder weather. Oh, it was lovely and warm when you came outside.'54 Ian Morrison’s father was also involved: £It was a co-operative cool store. You bought a share in it you see. Well Dad had two shares and then when I took over, I bought another share. I had three. It was mostly for pears, the cool store. The Packham pears were the main ones we grew - Beurre Bose, pick those in March and then sometimes we'd keep the Packhams till Christmas in the cool store.'55 Former Doncaster East resident, Dorothy McKenzie, remembers her father coming to work at the Doncaster West cool store: 'Father had been a refrigeration engineer most of his adult life. Prior to coming to Doncaster he had been an engineer at Tyabb. In 1938 he applied for and got the job at West Doncaster. It had been the first co-operative cool store built in the district. The engineer’s residence at the cool store went with the job. There was a gas combustion engine used in 1938. It later changed to electricity. My father Waldo Shepard died suddenly in 1945. My brother, Herbert Shepard, was away in Darwin at the time and had to be brought home to take over as engineer. He hadn't had any formal training, as my father had had, but he had 'learnt the ropes' through practical experience under my father’s expert guidance.'56

In 1914 a group of orchardists built the Orchardists’Cool Store. As an indication of how business was growing, this cool store had the capacity to store 120,000 cases. A year later orchardists using the Government Cool Store formed a co-operative and purchased that premises from the government. They renamed it the Central Cool Store. Templestowe fruit growers also formed a co-operative and in 1919 built the Templestowe Cool Store. The proliferation of cool stores was a manifestation of the burgeoning success being experienced by the orchardists of the area. With over 7,000 acres in the district given over to orchards, production reached its peak in the 1920s. There were more than 400 stand-holders at the Queen Victoria Market from the eastern metropolitan fruit-growing area alone - far more than from any other district.57It did not get much better than this.

At the peak of production the co operative cool stores in the Doncaster Templestowe district had a total capacity of 200,000 cases, while the privately owned stores could hold about another 43,000 cases. With the exception of the original store, the w hole of this capacity was provided by the growers without assistance from the government. Source: Keogh, p. 34.

To market, to market

Uncle George was the marketing man of the partnership. He would leave for the markets at 9 o’clock at night, driving very slowly down the road. It was a bit of a joke. People would see him and run along beside the truck. He went so slowly because he didn’t want to bruise the fruit. H e presented it in beautiful condition at the market. Uncle George was a perfectionist with fruit packing and would drop off specialty cases of his very best fruit to M r Jonas’s shop at the top end of Collins Street. Source: Peter Adams, interview, 16 May 2001.

The earliest fruit growers of the area sold their produce at kerbside markets and at the Fitzroy W ood Market; later they also used Paddy’s Market near the centre of Melbourne. In the nineteenth century, pears, apples, cherries and plums were sent by sea to Brisbane and Sydney markets, and New Zealand also offered a significant market for cherries. With the advent of refrigeration came an export market to the United Kingdom and Europe that was particular ly strong during the 1930s. But it was the Melbourne market that continued to be the major source of income for most orchardists.58 From its opening in 1878, the Queen Victoria Market offered the most coveted site for sales: ‘There was a stand where my Uncle George would sell if he was first to arrive. If he didn’t arrive early, someone else could have it, and he would stand in the market alongside many other Doncaster/Warrandyte orchardists. They would converse, and then go off and have their breakfast after sales at one of the little cafes around the market - friendly competitors. Many of the orchardists were related either directly or by marriage, so they usually got on pretty well. There was a marketing man for each family and other members of the team would be doing the day work, commencing at eight o’clock or earlier and sometimes until dusk. There was co-operation between families and within them, a team effort to get the fruit to the market at the right time and in the best condition - and of course competition there to get the best prices.’59 Part of this competition required an ability to assess the day’s trade: 'You'd get in there a bit before it started and youd sometimes have time to have a look around and see how much fruit was in there. My brother was good at judging the market. One day he'd say, 'There’s not much in today. Sit on your fruit and don't sell it cheap'. Another day he'd say, 'There’s a lot in - get rid of it early'. I didn't go to market regularly all the year round. I'd go in summer with the peaches and then I'd knock off for a while, and then I'd start with the pears out of the cool store - I'd get perhaps forty cases out of the cool store and take them home and pack them up and then go to market the next morning.'60

The beginning of the end

The Great Depression of 1929-30 hit everybody hard, although orchardists, like many peo- ple on the land, were perhaps a little inured from some of its harshest vagaries. They were able at least to ensure a food supply for their families; but the economic catastrophe certainly had an impact. Prices for fruit fell so low that sometimes it would actually have cost the growers money to take their fruit to market. It simply was not worth the trip. If the Depression did not precipitate the end of the orcharding era in Manningham, it certainly turned the tide towards it. It was perhaps the first of a number of factors that would, over the next thirty years, gradually see orcharding in the area decline.In 1937, a fire at Doncaster’s largest cool store, the Orchardists' Cool Store, was a disas- ter. The fire ravaged the east building and destroyed the refrigeration plant and 50,000 cases of fruit.61 Vital storage space was lost at the height of the pear-picking season, and the west- ern section of the cool store was packed to capacity with no cooling system in operation.62 Then, in 1939, when Britain declared war on Germany, Australia too became embroiled in that distant conflict. Orcharding was a protected industry, which meant that some men of eligible age were directed to remain working within the industry: Everything slowed down through the war. Melbourne had continually expanded. I cannot remember when there were paddocks down in North Balwyn east of Burke Road, but my parents could. All the way to Doncaster were paddocks - not fruit-growing areas, just paddocks. As Doncaster expanded and you got younger generations of fruit-growing families - it was an expectation that each 96 son would become an orchardist - there was just no room for them here. So areas further out became natural extensions of the Doncaster area.'63 As early as 1945, applications and plans for subdivision of areas in Manningham, including the orchards, were being received for consideration and approval by Council in increasing numbers.64 'Just after the war a few subdivisions started to come in and the War Service people bought land at East Doncaster and developed a settlement there. That started the cycle of selling for residential purposes.'65

Henry Zerbe, Tilly Aumann, Rupe Holloway and Ted Holloway picking pears in Zerbe’s orchard, 1917. (Photo: DTHS)

Correspondence from Mr A. N. Williamson: William sons Road and Mr J. S. Read: Serpells Road. With reference to their son in each case, having to appear before the Manpower Officer. Moved ... that the area officer be advised in each case, that their Father [sic] owns certain acres of Orchard. Source: Council Minute Book, Shire of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1942, pp21-2

The Engineer addressed the Council at length re the latest building regulations; and suggested that the w hole of the shire be proclaimed a residential area; so that the subject of factories w could be eventually under the control of the Council. Source: Council Minute Book, Shire of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1945, p. 142.

As the new generations of orchardists moved further out, the suburbs of Melbourne seeped closer to the older orcharding properties. Land value increased and the rates went up. It soon became either too expensive to stay, or too lucrative not to sell. One by one orchardists began selling. Lionel Tully recalls how difficult it became for orchards to remain financially viable: At those times we weren't making enough money from the orchards to pay the taxes. Subdivisions started before rates went up. Ail you got from the Council was, 'We'll buy your land from you for that price'. From £40 the rates went up to £340 in one year and it was nearly the same in land tax. In those days, that was a lot of money. We could keep house and save on £3 a week. You were working for everybody but yourself. We sold out in pounds and got paid in dollars in 1966.'67 Ian Morrison tells a similar story: 'The family orchard was on Wilson’s Road. My grandmother’s people had settled there in the 1850s. The orchard next door, Tully’s, sold out before we did. As orchardists we had been on a primary-producer reduction for rates. Then the unimproved' rating came in and the rates went up from £20 to £400 per annum.' The rise in rates was not the only incentive to sell: 'The orchards on the other side of Koonung Creek had all got sold and they were getting built on and there were a lot of kids growing up over there. There was nothing much for them to do, but I had four dams on the property at this stage and that was a big attraction for the kids. They'd come over here. I didn't mind them fishing for yabbies. There was even some fish, carp, in one of the dams. I didn't mind them doing that, but if the fish or the yabbies didn't bite, the kids would get up to mischief. They'd pull up the stakes that I'd have propping up limbs or have pear fights - things like that. They'd come in after school. They got in once and cut my watering pipes. I got a bit sick of it in the finish and that was another reason why I sold out, because the kids were becoming such a trouble. I sold, I think, at the end of 1962.'68

The last of the Thiele orchards was bulldozed in 1966. Eric Collyer can remember the scene that greeted him upon coming home: 'Two-thirds of it was gone, just with a bulldozer in one day and then they did the rest the next day - the fruit trees only. That was four generations' work gone in two days, over a hundred years of history just razed to the ground in two days.'69 Norma McMurray remembers the effect such changes had on her father: A lot of the orchards were going and my Dad had to sell up in the early 1970s because it was no longer viable. Dads orchard was bulldozed around 1973 and it nearly killed him because he had planted those trees. It all sort of went very quickly. The orchards disappeared very quickly in the 1960s and 1970s.’70 From 1960 to 1970 the population of Doncaster-Templestowe grew from 15,000 to 64,000 and the orchards were reduced to 2,000 acres.71 We conclude then with the image of bulldozers pushing over acres of healthy and productive fruit trees. It is a brutal image, a sad place to end a chapter on the history of orchard ing; but it is an important image because it defines a pivotal moment in the history of Manningham. The region was changing from a predominantly rural environment to a suburban one. But the image also serves as an echo from an earlier period when healthy and fruitful native vegetation was felled in the name of clearing the land’. And if we are saddened a little by the passing of the orcharding era, then we might pause to consider the sense of sadness and loss experienced by the Wurundjeri, the first people of the region. They, too, once lived and toiled in ways that are no longer obvious in the landscape of modern-day Manningham — and for a much longer period of time than did the orchardists.

Templestowe was an apple orchard when I came to live here twelve years ago, except for a few houses. N ow new houses have spread all over and not a single apple tree can be seen lovely! Source: Sam Chen, Suburban Voices - oral history project, Whitehorse Manningham Regional Library

Source: Barbara Pertzel & Fiona Walters, Manningham: from country to city, Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2001. Manningham Council granted permission to reproduce the book contents in full on this website in May2023. The book is no longer available for sale, but hard copies of the original are available for viewing at DTHS Museum as well as Manningham library and many other libraries.

No comments:

Post a Comment