Environment

Whether or not there is a world out there independent of our perceptions. The ways in which we perceive, imagine, conceptualise, image, verbalise, relate to, behave towards the natural world are the product of cultural conditioning and individual variation. George Seddon, Landprints (1997)

Three miles downstream from Yarra Glen is the Yering Gorge. Most gorges are formed by rivers cutting their way down to a lower level, but this one was formed by a fault which caused the land to the west to rise very slowly, so that the downcutting of the stream was able to keep pace with the uplift o f the land, and thus produce a narrow steep-sided valley which extends to the Warrandyte Gorge, about 18 miles from Melbourne. Near Templestowe, the Yarra emerges from the Warrandyte Gorge to enter a broad, mature valley with wide alluvial flats, through which it flows gently to Fairfield, where it narrows and becomes youthful again. (1 Len Allen, ‘A river valley: the Yarra, in The Essential Past (Sydney: The Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1969), p. 65)

As with all human groups, the way they lived on the land also brought change to their surroundings. We do not fully understand the extent of these changes but two aspects of the Koories way of life - the use of fire and the dingo - must have had a visible effect. Fire was used as a means of clearing parts of the land so people could travel more easily through it. The burning also fostered new plant growth which attracted game. Over a period of perhaps a thousand years, some plants adapted to periodic firing and eventually became the most com m on or dominant species. ... The dingo was the only animal in Aboriginal Australia that could be usefully tamed. But the dingo is not native to this continent. ... It is almost certain that [the Tasmanian tiger’s] disappearance from this landmass was a direct result of the introduction o f the dingo by Aboriginal people. Source: Presland, pp.13-14.

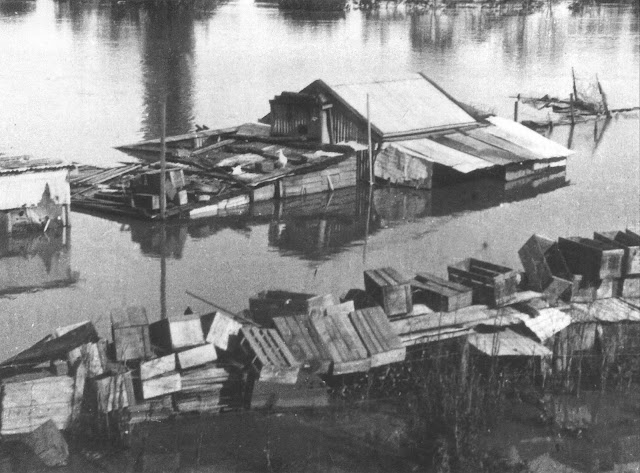

Before dams and diversions were built upstream, the volume of water carried down to the sea by the Yarra was double its present capacity. (2 Isabel Ellender, The City of Doncaster and Templestowe: the archaeological survey of Aboriginal sites (Doncaster, Victoria: Victoria Archaeological Survey; Dept of Conservation and Environment, c. 1991), p. 5). Flooding was common. Compared to what the Yarra itself did to the environment of its flood plain before European settlement, the human impact of the first people there, the Wurundjeri, was minor. This is not to say that they did not modify and exploit the river-flat environment extensively. They did.

Archaeological research in the area has uncovered samples of evidence of the Wurundjeri-willams ancient presence. Archaeologist Isabel Ellender was commissioned by the municipality to survey Aboriginal sites in 1990. Of a total river-flat area of 11 square kilometres, Ellender studied 0.02 square kilometres intensively. Only six archaeological sites were identified. Three of these were scarred trees, two of which were found along the immediate riverbank, and the third on a river terrace. The scars suggested that each had been used for a different purpose - as a shelter slab, as a shield and as a container. (3 Isabel Ellender, The City of Doncaster and Templestowe: the archaeological survey of Aboriginal sites (Doncaster, Victoria: Victoria Archaeological Survey; Dept of Conservation and Environment, c. 1991), pp. 40-1). Three more sites, two described as 'artefact scatters', and one described as an 'isolated artefact', were also found on the river flats. These consisted mainly of debris from the manufacturing of stone tools, as well as several finished tools. (4 Isabel Ellender, The City of Doncaster and Templestowe: the archaeological survey of Aboriginal sites (Doncaster, Victoria: Victoria Archaeological Survey; Dept of Conservation and Environment, c. 1991), p. 37). Further sites have since been discovered, and other areas of Manningham may yet be studied, but most of the archaeological evidence for thousands of years of occupation appears to have been obliterated. On the riverbanks, the major cause of this obliteration, according to Ellender, was the effect of repetitive flooding (5 Isabel Ellender, The City of Doncaster and Templestowe: the archaeological survey of Aboriginal sites (Doncaster, Victoria: Victoria Archaeological Survey; Dept of Conservation and Environment, c. 1991), p. 41). The results of her survey clearly point to a human impact on the environment so minor (compared to the effects of the river that ran through it) that much evidence of the Wurundjeris presence was largely reclaimed by nature. Then, from 1835, the effects of European settlement further overlaid or completely obliterated evidence of Wurundjeri occupation on the flood plain and elsewhere, and brought major, ongoing change to Manningham's environment.

From the time when only the Wurundjeri people settled the district to the present, aspects of Manningham's environment have altered dramatically. We cannot chart them all but we can look at the history of some of those changes. The following views expressed by some of the citys residents demonstrate that perceptions of Manningham's environment, or what constitutes it, are as varied as the people who conduct their lives within it.

An artefact scatter is a surface scatter of more than 4 artefacts within a radius of 5 metres. This may be the residue of a base camp or of a temporary stop. ... Isolated artefacts are usually found anywhere and are probably random discards.

Not suitable for farming any more

Dramatic changes to the whole of the area that is today the City of Manningham are within living memory. Where now members of Manningham's Italian community enjoy social gath- erings at the Veneto Club and where Trinity Grammar, Marcellin College and Carey Baptist Grammar conduct sporting events on manicured playing fields, cows once grazed.

Illona Caldow, a member of one of Bulleens former dairy farming families, recalls her childhood in the 1950s on the river flats: 'Then it was just farmland. That billabong was something really beautiful and we loved playing around there. It had so many water hens and ducks and swans. Father had a problem with people who would come and shoot the ducks.

People, young and old, from the 1930s to the 1950s made much more use of the Yarra than today. Anglers were seen at all times heading for the river. There were many swimming holes along the river. We had ours on a bend in the river opposite the Springbank property, where there was a sandbank. At times, having gained permission from the then owners, we were able to ford the river to trap rabbits on what is now known as the Bolin billabong. We also had canoes so we knew the river well. Source: Ron Taylor, 2001.

We had “No Shooting” signs up along Bulleen Road; but in the middle of the night quite often you would hear people shooting. The river - it was just fantastic playing around the river and the billabong. A few of my brothers friends had horses and we used to have races where Trinity is now. Where the Freeway is now, there was M cColls Riding School — that was on the west side of Bulleen Road. Across the road from that was Mr Cox, a gentleman with a few acres of land. That is where Camberwell Tennis Centre is now. Then you come to where my uncle had the property Ben Nevis. That went to both sides of the road. Our farm was the next farm to that, so we were close together. He had a dairy farm also. That was where Carey now is, and where Bulleen Park is, that was a part of his farm until the Council bought it for a tip. It was a tip for many years. O f course, where Marcellin is, that was a part o f his farm also. The house is still there.’ (6 Illona Caldow, interview, 21 February 2001)

When the earliest European settlers arrived, the well-watered flood plains of the Yarra River were rich in pasture suitable for grazing herds of sheep and cattle. We remember that in 1857 Robert Laidlaw purchased 90 acres of river-flat property, and over the next twenty-four years built up his holding to 300 acres, some owned, some rented. (7 Shire of Bulleen Rate Book 1881, Templestowe Riding Nos 64-68). Laidlaw made a great suc cess of farming on and around the river. His property, known as Springbank, was sold in 1925 to a former Lord Mayor of Hawthorn, who renamed it Clarendon Eyre and used it as a Jersey stud farm. Then, in 1946, Clarendon Eyre was purchased by Robert (Bob) and lima White. Illona Caldow remembers: ‘I was only 4 when I came here. The extended White family had three properties in Bulleen - Clarendon Eyre, Ben Nevis and Arunga Park - which all supplied milk to White’s Dairy in North Kew, run by my Nanna. It was very good grazing land on the river flats and my father always said it was one of the best properties for dairy ing.’ (8 Illona Caldow, interview, 21 February 2001). The Whites ran Clarendon Eyre as a dairy farm until the 1960s. By then the farming environment of the area had started to change.

Bulleen was being developed, becoming more of a built-up area. Maris and Ron Taylor purchased a block of land in 1953 but did not build their home until 1957: We were attract ed to the then shire because of its large, open areas. We believed it would progress. It has been our home for forty-seven years.’ (9 Maris and Ron Taylor, questionnaire, 22 June 2001). Bulleen was the place where Doncaster East residents Faye and Jeff Lee first bought into Manningham. ‘We had friends who spoke to us about a new residential estate that was off Manningham Road. It was supposedly on a “green belt”, so we had agistment properties behind with cows grazing there and we thought, “Oh this would be lovely. You'd never get built out'.' The fact that the subdivision was in the area where her mother had spent quite a lot of her childhood was another plus for Faye, who is a great-great- grandaughter of Major Charles Newman: It was really nice to come out this way and put together all the things I'd been told about the place as a child'. Jeff remembers they built their new home and moved into it in July 1958. It was thirty years exactly we lived in that house, and the locality came on a long way in that period. When we first moved in everything was very basic. We were proud of our dwelling, but there was no sewerage, just a septic tank, the electricity supply was limited and there were no made roads, no shopping centre.' Conditions were very trying for Faye. 'When our boys came along I had a white pram and I used to have to put gumboots on to push this white pram along the streets. I'd change into shoes and wait for the bus, then coming home again it was back into the gumboots. I used to have to hose down the pram because it would be covered in black mud. Reflecting on it now though, there was a sort of joyousness and happiness, you know, just being there and having your own home.' (10 Faye and Jeff Lee, interview, 19 June 2001)

For the Whites, however, the advent of suburbia near the perimeters of their farm in the early 1960s signalled great change. They began to have trouble with domestic pets: 'Packs of dogs would attack the little calves. Then, you couldn't have cows here any more because Bulleen Road was coming through and we needed both sides of the road to farm them. The rates were becoming expensive and it just wasn't suitable to farm here any more, so my parents decided to subdivide.' The Whites were unable to subdivide immediately because the Education Department wanted to buy land on their property. The school wanted the highest part of the farm. The Whites had to wait quite a few years until the Department built Yarraleen School, in Balwyn Road, Bulleen, before they could start to subdivide - and then they did it all themselves: 'They had a contractor to make the roads and Mother sold the land. I think she liked the contact with the people that she was selling the land to. That was in the late 1960s, early 1970s. Illona Caldow had by then married and moved out of the family home, as had her brother. Towards the beginning of the 1970s the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW - now Melbourne Water and Parks Victoria) had approached the Whites to discuss what they were planning to do with the land: 'My parents were quite happy about their approach because they loved this land and they didn't want to see anything happen to it. They wanted to see it in its natural state. And they would have been quite happy to sell the high land and the house to the Board of Works then too. But when the Board of Works did their sums later on, after my parents had died, they decided that they didn't want that high land. They took all the low land round the billabong and all the other low land, and they did buy some of the land to the south. That’s all high land, but mainly it was river flats that they bought.'

The high land around where the house, Clarendon Eyre, is situated, was eventually subdivided in 1986: On that land there was also a three-bedroom house, a dairy, stables with a loft and farm outbuildings. The 1986 subdivision was our only choice. We didn't want to sell it to developers, so we decided we would go ahead and develop it ourselves because we had more control. The dear old Council wanted this land but they didn't want to pay for it - more parkland perhaps.' In 1983 a Council Committee had requested the MMBW to reconsider purchasing more of the Whites' land, offering to contribute funds towards the acquisition, but the parties involved could not agree on a fair value: 'Every time we put a plan in to Council they would reject it. Then it would have to go to Tribunal, even though the Board of Works more or less agreed with everything we were doing. We were prepared to sell, but we wanted a fair price because it was zoned reserved living - it wasn't open space land.' (11 Illona Caldow, interview, 21 February 2001). The Council Committee argued that it was only the hectare around Clarendon Eyre that was zoned 'reserved living, that this was wrongly included in the valuation and that 2.6 hectares nearby should maintain a 'proposed public open space' zoning, thereby altering the valuation considerably. (12 Council Minute Book, City of Doncaster and Templestowe 1983, item 1.1, 1 March 1983). 'They wanted to class it with the open space or river-flat land, which it wasn't - they must have known that it was all reserved living land. A lot of propaganda went on in the paper that we didn't reply to. It was a hard time. It was a bit hurtful. But anyway, we got it through eventually.' (13 Illona Caldow, interview, 21 February 2001). The Council viewed the process as a fight to save the Whites' land in Bulleen from development, to preserve it as open public space in the Yarra Valley Metropolitan Park. The Whites were willing to sell, but for a fair price, and preferred not to sell it to developers. What could have been a parkland environment eventually became a built environment.

With time even the built environment of Bulleen changed in a way that no longer suit- ed Faye and Jeff Lee: 'Eventually you could see subdivision going on in our beautiful green belt - roads being put down, all the storm water drains and so forth. You'd see houses being built and then suddenly this double-storeyed monster side by side with another one would be looking down into your establishment. When we first came here we had a wire fence at the back. We didn't have a wooden fence for years. The boys could feed the animals. We had cat- tle lowing at the back. We could look out and see our 18-month-old toddler out in the back paddock patting the backside of a huge horse. Eventually we moved because privacy became a factor. In Bulleen we were window to window - you'd open the Venetian blinds and wave to your neighbour.' (14 Faye and Jeff Lee, interview, 19 June 2001). Faye and Jeff Lee eventually sold out and moved to Doncaster East. The built environment of Bulleen altered, the parkland environment was never fully realised, and the farming environment that was once there vanished completely.

Subdividing the garden

Many who came into Manningham in the 1950s believed they had found a place to live that embodied the best of both worlds - a country environment close to the city. Don and Nell Charlwood’s first impression of Templestowe was that fit was just such astonishingly beautiful country, changing with the seasons when the orchards were in flower and later on when they'd all lose their leaves'. (15 Nell and D on Charlwood, interview, 14 June 2001). Doncaster East resident Lois Rae remembers: cOur home was built in 1959. At that time this area was orchard country and the rural atmosphere was the appeal. In the early days it was a joy to walk from the bus in the evenings and see the setting sun through the trees in the orchard. We had good, clean air, no noise pollution.' (16 Lois Rae, questionnaire, 22 February 2001)

Doncaster resident Ken Sharp remembers his first trips out to the district in the 1960s, before he came to live there. He was able to observe the changes coming: At work, I was given a client to attend to in Doncaster and I vividly remember driving to what was then known as White’s Corner, where Doncaster Shoppingtown now is, and that was the end of the made road. To be honest, I'd never heard of White’s Corner until I made this journey. It was this old corner store, which was a typical Australian store with a verandah. Back then I thought, 'Why would you want to go beyond this point? What is beyond there? Why would anyone want to live out here?' This was the edge of civilisation. I was living in Northcote then so Doncaster was almost country to us. I did manage to navigate my way to the client’s house. It was up to Whittens Lane, which is opposite what is now the Civic Centre, turn right - also unmade road, and turn left at the first or second street, which was a new little estate with made roads.

There was a certain amount of glee when I got onto this made road and this particular guys house was probably one of about four on a new little estate that was obviously ex-orchard. I used to sit at the clients dining room table and look out over the hills and over the nearby orchards. Over the years that I was there working, bit by bit, you would see the orchards slowly disappear and more subdivisions, more blocks carved out, more houses. Every year, bit by bit, the orchard was getting smaller, and in the distance it was slowly being replaced by houses - trees down, and bareness and all that sort of business that comes with subdivision. I would see this guy probably once or twice a year, sometimes more, and I would notice that almost every time I went there, there was a big, dramatic change. (17 Ken Sharp, interview, 31 May 2001). In the 1980s changes even to the built environment in some parts of Manningham were very dramatic. Lower Templestowe resident Lesley Taylor and her husband moved there in 1984 when they purchased their house: 'There used to be many more vacant blocks, some even had horses grazing on them. Many of the old, huge pine trees have gone. Several smaller schools have been closed and are now housing estates. The newer houses seem to be large houses on smaller blocks, leaving very little garden. (18 Lesley Taylor, questionnaire, 8 December 2000)

How do we regard an environment: as something static; as a place that we do not want to change because we prefer it the way it is; something that can be saved or preserved? Author and former Templestowe resident Don Charlwood reflected on changes that occurred to his family’s living environment in that suburb in a piece he wrote for the Warrandyte Diary in 1997. Reproduced here, with his very kind permission, is an edited version of those reflections. They led him to draw a telling conclusion.

Forty-five years ago, along with other ex-servicemen wearying of rented rooms in suburbia, I discovered this rural haven less than an hour from the city, country where hillsides of peach, pear and nectarine grew in ordered rows, tended by people whose families had been tending them for three or four generations, many of them old German families. Set among the trees were numerous dams for summer watering, mirror-like in the sun.

To our surprise we heard that some of these people were selling off a few acres of their orchards. Though this seemed like sub-dividing the Garden of Eden while God’s back was turned, we bought eagerly. For £450 from my RAAF deferred pay, I bought just under an acre, on it a hundred lemon trees. We heard then that a green belt was to be declared to limit sub-division. We exulted; we had bought just in time! We would have rural surroundings for the rest of our lives. ...

In June 1953 we moved in. ... Our children had started at the one-roomed brick school, attended till now by generations of orchardists' families. We all soon learnt to speak no ill of the locals; their web of relationships was beyond unravelling. They were kindly people who didn't much bother to lock doors; they were always ready to stop for a yarn and to help a neighbour; they provided bountiful piles of fruit and vegetables for church Harvest Festivals.

We danced and held fetes at the 1922 Memorial Hall, but our main community centre was the rambling post office-store, its floor worn, its wooden counter long, its verandah wide. It seemed to carry everything, though often it took long for items to be found. While we waited and gossiped, we breathed the scent of chaff and pollard from a cavernous old hay and corn section next door. Across the road was the blacksmiths where children paid homage to Jack Mullens, resident saint of the forge. His anvil rang, horses stamped and whinnied. Though few orchardists still used horses, Jack drew a clientele from outlying pony clubs.

A generation of younger do-it-yourself people began moving in, a rather better- heeled generation than ours and better informed. They employed architects, further- more their architects were well acquainted with the edicts of Robin Boyd. Their houses were long and low and blended with the countryside. This new generation favoured native trees.

Most of the orchards were still being worked. Sometimes we fancied that the orchardists' seasonal round was a pageant put on for our delectation. We joined the newcomers in raising money for a kindergarten and a Guide hall. The orchardists were faintly amused; in their lives there had been no time for such fripperies; children had been a source of labour. They good-humouredly dubbed us city slickers'.

Before the sixties began we gained a hardware, a butcher, a pharmacy, but we lost the post office-store. Also, adjustments' were being made to the green-belt concept; it was shrinking rapidly before the onslaught of 'developers'. We city slickers began discussing what we wanted for the Templestowe of the future. Green corridors, we reckoned, contoured roads, acre blocks, houses in harmony with the countryside - nothing to spoil what we possessed.

It was too late. By the time our fourth child was at the old school, relentless development had begun. Orchards were being bulldozed, their owners declaring, cWe cannot afford not to sell!5 Who could blame them? They were gaining more than they or their fathers or grandfathers had dreamed of. Their cherished trees were now in heaps for burning; developers rejoiced among the funeral pyres.

What now? The outriders of a new generation arrived in Mercedes and Range Rovers. They were the ‘super slickers5. They did not seek to build houses; they built mansions. Our generation laughed at their first grotesqueries, then we cried, for all the orchards were swept away and the Walt Disney school of architecture took over our hill- sides. Bizarre mixtures appeared sporting classical Greek columns, imperial eagles, multi- gables of Tuscan tile, Tudor half-timbering. They overflowed their boundaries like so many dowagers5 bosoms. Many were fronted by Buckingham Palace gates electronically operated, patrolled by pairs of german shepherds, dobermans, rottweilers. The once quiet hills resounded to burglar alarms and the baying of guard dogs. Gone were unlocked doors.

The super slickers had no need for the old school; its numbers fell. After 120 years of use it was closed. Aged orchardists and middle-aged children of the first city slickers attended its obsequies. We who had sought escape from suburbia had paved the way for ostentatia. We had witnessed the loss of a way of life.

Don and Nell Charlwood now live in Warrandyte.

Delivered to your door

For housewives in the 1960s, the advent of Shoppingtown, which was eventually built in 1969 on the site occupied by Whites Corner Store, forever changed the character of the local shopping environment. Judy Conway has lived in Doncaster since she and her husband bought a new four-bedroom home in 1968: It had a large garage and plenty of back garden where our future children could safely play. The building and extensions to Westfield Shoppingtown led to the gradual loss o f the local shopping strip on Doncaster Road.’ (19 Judy Conway, questionnaire, 24 December 2000)

The Shoppingtown site occupies an overall area of approximately 14.7 hectares. At present, the Planning Scheme allows for the expansion of the shopping centre to a maximum of 90,000 square metres of gross leasable floor area and 135,000 square metres of total floor area. This represents a doubling in size o f the existing shopping centre. Source: Manningham City Council fact sheet, 1997.

Gone forever perhaps is another shopping environment that only the residents o f the district who lived in Manningham before World War II would perhaps recall: ‘I can remem ber the milkman who used to come early in the morning and deliver the milk. Mr Gallus used to milk his own cows then deliver it round the district, although not to everyone because some people used to keep their own cows. I can remember my mother put the billy out, inside the back door every night with the money. He would come round, probably about 6 o clock in the morning with the stainless steel bucket and a long ladle, and he just ladled the milk out of his big bucket into the billy.’ There were Lauers, the bakers, who made bread in their bakery off Victoria Street in Doncaster. The bread was delivered all round the district from a bread cart drawn by a horse: ‘The baker would call out at the back door with a basket of loaves on his arm, and you could select what you wanted and pay your money. He would put the money into a leather purse that he wore on a strap.’ There was the ice-man, Mr Keep. He used to deliver blocks of ice for the ice-chest, which was how things were kept cold before the days of refrigeration: cH e’d wrap a block of ice in a hessian bag, carry it under his arm on his hip, come into the vestibule we had then, and put the huge block of ice - probably about 15 inches long, about 12 inches wide and about 10 or 12 inches high — into the ice-chest for Mum because the ice was very heavy, and then Mum would pay him.’ The ice slowly melted in the top part of the ice-chest and the water went down a pipe and dripped into a tray on the floor under the chest. cYou always had to remember to empty the tray because if it overflowed, you’d find a pool of water on the linoleum around the ice-chest and you’d have to mop it up.’ The butcher and the grocer would also deliver to the door. £Mr Mitchell was the grocer. He had a beautiful little old shop in Doncaster Road. One side was haberdashery and the other was groceries - a country store. Mitchell’s shop had originally been Thiele’s general store. It was not very big. I go into a supermarket these days, look at what’s on the shelves and wonder how it would ever fit into a country grocery store, yet somehow, back then, we managed.' Sometimes a market gardener would come around to the houses in the district selling fresh vegetables from his van, but many people used to grow their own vegetables. Occasionally a fishmonger would bring fresh fish around for sale. cIt was very much home delivery in those days'. Sometimes a trip would be made to the grocer shop. 'Biscuits were always sold from the tin, a big tin. They were put into a paper bag from the tin. If you wanted cheese it was cut from a big block using a wire. You'd go into the shop, up to the counter, give the grocer the list and then you'd just sit there. He'd get everything for you then put it on the counter. All you had to do was pay him and put the things in your bag or basket. The shop was a place where you would often meet and chat with local identities.' (20 Interview with Eric Collyer, 12 June 2001)

A wedge of green

Much of the change experienced by residents to their country living environment took place while Melbourne’s planning authorities were still developing planning strategies and policies. Managing the outward growth of Melbourne’s metropolitan regions is an ongoing process that arguably began in 1929. The Report by the Melbourne Town Planning Commission came out that year and was responsible for setting town-planning legislation for Victoria. It was not until 1949, however, that the Board of Works (later MMBW) was actually asked to prepare a metropolitan planning scheme for Melbourne. (21 Report on proceedings of the seminar held at Monash University on 26 February 1972 on the Board of Works report ‘Planning Policies for the Melbourne Metropolitan Region, p. 4). In the intervening twenty years, the Great Depression and then World War II slowed development, but after the war Melbourne’s population expanded rapidly, greatly increasing the demand for housing. In 1954 the Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme and Ordinance was made public, but it was not finally approved until 1968. Meanwhile various proposals and recommendations were put forward. A corridor-wedge concept' for planning and managing the future growth of metropolitan Melbourne was first proposed in a report to the State Government by the Board of Works in 1962. In 1967 two reports, one by the Town and Country Planning Board and the other by the Board of Works, presented recommendations regarding the outward expansion of Melbourne. The Board of Works report recommended a 'Corridor-Satellite' approach to development along several established transport routes. It also recommended that one or two satellite towns be built in the north and west with the aim of redirecting development in those directions, thereby easing the rate of development to the east and south-east. The report fur- ther recommended that in between these corridors of settlement, wedges' of non-urban land be preserved as 'breathing spaces' within easy reach of urban development. (22 T. Dingle and C. Rasmussen, Vital Connections: Melbourne and its Board of Works 1891-1991 (Ringwood, Victoria: McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1991), p. 312). This was the beginning of the 'green wedge' concept.

Westerfolds Park is part of this very special wedge of green, and the history of its preser- vation as open space illustrates the kinds of tension that continue to complicate efforts to pre- serve 'green wedge' land for the municipality of Manningham. (25 See for example Warrandyte Diary, July 2001, p. 5, ‘The Green Wedge Debate - Yet Again’). During the 1960s Jennings Estate and Finance Ltd made several unsuccessful applications to develop farmland that had formerly been the Westerfolds Estate and Paddles land in Templestowe. At the same time con- servationists, such as the Yarra Valley Conservation League, were opposing any subdivision. The League believed from the outset that the precious riverside land, like all that bordering the Yarra River, should be zoned as public open space available to the whole community for passive recreation.

The purpose of Council is to achieve and maintain a physical and social environment of such quality that people will acknowledge the City of Doncaster and Templestowe as a preferred place to live, work and visit. Source: Staff induction handbook, City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1989.

Aware that the Doncaster and Templestowe Council wanted to retain open space in the municipality, Jennings tried a new approach in March 1970 in which just over half the land would be developed for housing. Their plan proposed a trade-off - if the Council would agree to rezone part of their land from rural to residential, they would sell 148.2 acres to the Council for the sum of $100,000 and undertake to build an eighteen-hole golf course on 93 acres of it, leaving the rest as public open space. (26 Doncaster Mirror, 14 April 1970)

From any point of view, the proper planning of the Yarra Valley is vital to Melbourne’s future. It is essential to know what areas are required for open space, parkland and the like, since this valley contains so much that must be preserved at all costs and means so much to Melbourne residents of the future. Source: Hon. Rupert J. Hamer, Minister for Local Government, cited in Yarra Valley Conservation League Newsletter, No. 9, October 1968, p. 1.

A year passed. In 1971 it was reported that Jennings had lost confidence that any decision would be reached and had therefore applied to develop the land within the existing zoning and withdraw the golf course and open space offer. Objections again ensued from the Yarra Valley Conservation League, the Doncaster and Templestowe Conservation Society and many individuals. Two more years passed. In 1973 the Save Westerfolds Committee organised a petition to state, federal and local governments expressing opposition to any development. At the Town Planning Appeals Tribunal, Jennings5 plan to subdivide 66 acres of the property was allowed but the company finally offered to sell to the State Government and the Premier, Mr Hamer, arranged for the purchase of Westerfolds as public open space. (31 Doncaster Mirror, 8 May 1973)

The battle to preserve Westerfolds from housing development, which had lasted for over ten years, had been won but skirmishes continued. In 1974 the Westerfolds Park Association disagreed with the sort of modifications that the National Parks Service was planning. One point of contention was the sealed roads that were to provide access for the vehicles of rangers and eventually the public. The Association wanted the park to be 'kept in as natural a state as possible'. (32 East Yarra News, 30 April 1974). The conservation societies that had fought so hard against the housing develop- ment wanted to ensure that the park would be managed along the lines of a national park, even though its size meant that it would be called a regional park. (33 Doncaster Mirror, 7 May 1974). In 1976 plans were unveiled to make Westerfolds a regional national parks headquarters as part of Stage 1 of the parks development. (34 East Yarra News, 22 June 1976). The suggestion in 1977 to graze livestock on the property was thwart- ed by the problem of packs of dogs roaming Templestowe. A concept plan for the park was adopted in 1981, followed by criticism of the dustbowl caused by works underway to create car parking in 1983. (35 Doncaster Mirror, 15 March 1983). In November 1984 Westerfolds Park was officially opened. (36 Westerfolds’, Doncaster - Templestowe Historical Society Newsletter, March 1985)

It must be pointed out that the pleasant rural atmosphere of this lovely property has been very largely obliterated by its ‘development' by the MMBW . Source: McBriar, p. 73.

I think the wonderful parkland and open spaces in the Yarra Valley and the Warrandyte State Park, and elsewhere, such as Ruffey Lake Park, are obviously a highlight of the municipality and I believe they are the reason why people live in and like the area. Source: Sonia Rappell, 2001.

Today in Manningham, the term green wedge' is commonly applied to all non-urban use land, and land east of the Mullum Mullum Creek within the city’s boundaries. The City of Manningham has one of the largest networks of parks and open space in metropolitan Melbourne, 12.5 square kilometres of it representing more than 10 per cent of the municipality’s area. The 100 Acres Reserve in Park Orchards is one such space. This land had been partly cleared in the early 1900s and used as an orchard, then during World War II the army used part of the reserve for training activities. In the 1970s proposals were put forward to subdivide the area. These proposals galvanised community opposition, and a campaign was launched to secure the 100 acres as open parkland. In 1978 the Commonwealth of Australia, the State of Victoria and the then City of Doncaster and Templestowe purchased the 100 Acres Reserve. Today the City of Manningham manages this reserve, aiming primarily to preserve and maintain a viable example of the indigenous vegetation broadly representative of Melbourne’s outer eastern suburbs in natural relationship', and to allow passive recreation within it in the hope of encouraging an appreciation in those who use it of this lovely natural environment. The 100 Acres Reserve was listed on the National Estate Register on 21 October 1981. (37 Manningham City Council, 100 Acres Reserve Management Plan, February 1996, p. 3)

Warrandyte State Park is another magnificent open space in Manningham. The park preserves a diverse range of vegetation:

Along the river valley lofty Manna Gums shelter smaller trees such as Muttonwood and River Lomatia which are more commonly seen in the forests of East Gippsland. There are ferny creeks reminiscent of cool mountain forests. The dry slopes and ridges are dominated by open forests of Red Box eucalypts, the subtle blue-green of which gives the region its character. These areas are rich in wildflowers, particularly ground orchids. In all, more than 480 different species of native plants have been recorded in the Park. (38 Friends of Warrandyte State Park, Discover Warrandyte (Warrandyte: Friends of Warrandyte State Park, 1993), p. 13)

The story behind the preservation of the area as a state park began with a meeting called by the Doncaster and Templestowe Tree Preservation Society, which was held in Warrandyte on 20 June 1968. At this meeting interested members of the community discussed the possible formation of a park. (39 Yarra Valley Conservation League Newsletter, No. 9, October 1968, p. 2). In 1973 the State Government of Victoria approved the establishment of an area of some 800 acres to be known as the Warrandyte State Park. (40 Graham Keogh, The History of Doncaster and Templestowe (Doncaster, Victoria: City of Doncaster and Templestowe, 1975),, p. 84; In the 1980s a substantial addition was made to the park). The park gained some friends in 1982 - the Friends of Warrandyte State Park (FOWSP). The major aim of the group was to involve the community in the restoration, development and protection of the new State Park'. (41 Friends of Warrandyte State Park, Discover Warrandyte (Warrandyte: Friends of Warrandyte State Park, 1993), p. 15). This dedicated group of volunteers began by clearing weeds and rubbish, including rusting car bodies, from park areas, and has since diversified into bush regeneration work. Comprising Jumping Creek Reserve, Black Flat Reserve, The Common, Timber Reserve, Whipstick Gully, Pound Bend and Mount Lofty, the Warrandyte State Park is a refuge for many native animals such as kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, possums, wombats and the unique egg-laying mammals, the platypus and the echidna. (42 Context Pty Ltd et al., City of Doncaster and Templestowe Heritage Study: general report prepared for the City of Doncaster and Templestowe (Melbourne: Context Pty Ltd, 1991), p. 23)

The open space network within the City of Manningham comprises over 300 parks that provide a range of active and passive recreational opportunities, conserving and enhancing the natural and cultural resources of the municipality.

The thin grey line

In the context of debates concerned with public transport versus private motor vehicle use, an irony exists in Manningham. In the whole of greater Melbourne there is only one road named Tram Road, and that is in Doncaster, but you cannot catch a tram anywhere along that road. The naming of the road goes back to a time when Doncaster seemed to be leading the way in public transport. The first electric tramway ever to operate in the southern hemisphere came into service on 14 October 1889, and its route from Box Hill to Doncaster was along Tram Road. (43 Robert Green, The First Electric Road: a history of the Box H ill and Doncaster tramway (East Brighton, Victoria: John Mason Press, 1989), p. 33). A railway line to the east of Melbourne had been extended to Box Hill by 1882, and an extension of this railway line from Box Hill to Doncaster had been proposed in 1888. One Doncaster group opposed to the tram argued that it would provide the government with an excuse for not proceeding with the Doncaster Railway Bill. Perhaps they were justified. Despite later plans in the 1920s to run a rail link from Kew to Doncaster, and in the 1970s to run a railway line along the middle of the Eastern Freeway reserve, Manningham is still without a rail service of any kind. (44 Doncaster and Eastern Suburbs Mirror, November 1971). The Box Hill and Doncaster tramway service ran only until January 1896 when, in a general climate of economic gloom after the collapse of the land boom in 1892, it became unprofitable to run. (45 Robert Green, The First Electric Road: a history of the Box H ill and Doncaster tramway (East Brighton, Victoria: John Mason Press, 1989), p. 61)

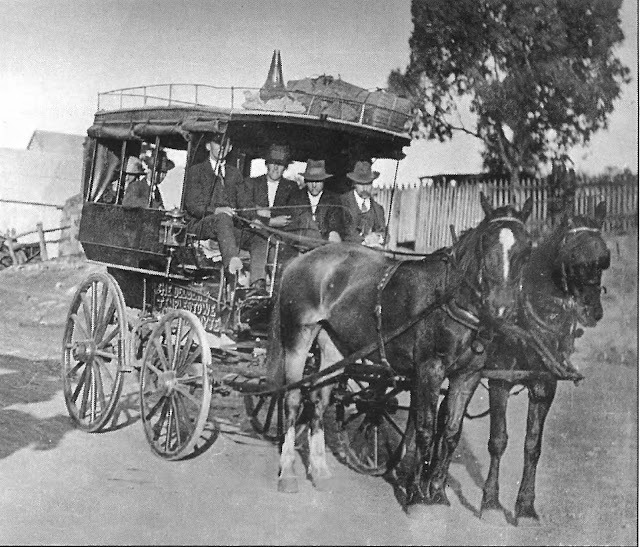

The development of an efficient and reliable public transport system in Manningham was hampered as much by the areas topography as it was by government indecision. From time to time private individuals endeavoured to make an adequate public transport service available. A .horse-cab operated from the Tower Hotel in Doncaster in 1886, taking passen- gers to Box Hill. In 1912a horse-drawn coach service operated by Victor Sonnenberg extend- ed its regular service, from Box Hill to the Doncaster Hotel, to Doncaster East. A bus service from Melbourne to Warrandyte commenced in 1913 but was out of service by the end of that year. A more reliable bus service between Melbourne and Doncaster, run by Mr A. Withers, began operation in 1925. (46 Collyer, Doncaster: a short history, (1981; rev. edn Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster- Templestowe Historical Society, c. 1994), pp. 73-4)

Murray Houghton has vivid memories of his experiences as a commuter on the bus that infrequently serviced Warrandyte when he was a boy: cIn 1936 Earle Stewart commenced the Warrandyte-Ringwood-Wantirna bus service. As a 5-year-old schoolboy, I was one of its first passengers. Sometimes I was its only passenger. It left Warrandyte at 5 p.m. for Ringwood on week days and during the wet winter months I was given a ride home from school to Jumping Creek Road for the princely sum of l1/2d. It was otherwise a 2lh -mile walk! After school, I stayed at the old boot shop then run by John Thomas 'Pop' Pridmore on the north-west corner of Anderson’s and Yarra streets, and listened to his endless yarns while he cobbled. Then around 4.30 or 4.45p.m. I would walk up to J. J. Moores store opposite the Tub' and go and sit in the little ten-seater bus and wait for either Earle Stewart or Frank Tresize, the reserve driver, to finish their afternoon tea break and then we'd set off at 5 o'clock.' (47 Murray Houghton, personal communication, 4 June 2001). A bus service for Park Orchards was only obtained in 1981, thanks to the efforts of the students of Norwood High School with some assistance from the Park Orchards Ratepayers Association. (48 Irvine Green and Beatty Beavis, Park Orchards: a short history (Donvale, Victoria: Doncaster-Templestowe Historical Society, 1983), p. 19)

Doncaster Heights - The Box Hill and Doncaster Tram Line will run through this Estate, thus connecting it with and bringing it within 15 minutes of the Box Hill Railway Station. This, together with the duplication of the Box Hill line, will bring Doncaster to within 40 minutes of the City. Source: Advertisement for Doncaster Heights subdivision, 1888, cited in R. Green, 1989, p. 25.

Although standards had not yet been adopted in Australia for acceptable noise levels, calculations indicated that noise levels likely to be experienced by Bulleen residents adjacent to the freeway, would not exceed those specified by the United Kingdom Department of the Environment. Source: Doncaster and Eastern Suburbs Mirror, 23 March 1977, p. 1.In the meantime, car ownership in metropolitan Melbourne increased dramatically, particularly after World War II. (49 T. Dingle and C. Rasmussen, Vital Connections: Melbourne and its Board of Works 1891-1991 (Ringwood, Victoria: McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1991), p. 234). As early as 1954 observers were warning that road traffic congestion was a rising problem, and without drastic measures to meet the approaching crisis, the ultimate strangulation of the city’s life appears certain. (50 The Age, 18 October 1954). To work towards easing traffic congestion, the Board of Works was given powers in 1956 to design and construct roads euphemistically defined as metropolitan highways'. 'Limited access roads', being able to carry the greatest traffic capacity, were seen as a viable solution to Melbourne’s growing traffic problems. These roads were to become known as 'freeways'. (51 T. Dingle and C. Rasmussen, Vital Connections: Melbourne and its Board of Works 1891-1991 (Ringwood, Victoria: McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1991), pp. 242-3). Reservations for most freeway routes were marked on the Board of Works' 1954 Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme and Ordinance. A schedule for implementing freeways to the east of Melbourne and elsewhere was ready by 1957, but was delayed due to problems with financing. Eventually in 1965 the government announced that a ten-year freeway building plan would soon begin. The proposed route for the Eastern Freeway (F19) through the Yarra Valley was approved in December 1970 - a decision subject to considerable public protest; however, in November 1971, as passionate disputes raged the Board of Works bulldozed 10 acres of the Yarra Bend National Park. (52 T. Dingle and C. Rasmussen, Vital Connections: Melbourne and its Board of Works 1891-1991 (Ringwood, Victoria: McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 1991), pp. 318-19). The thin' grey line of the Eastern Freeway had begun to snake its way towards Manningham and the valley of the Mullum Mullum Creek.

In 1973 the Mullum Valley Freeway Action Group sponsored two public meetings; they were attended by 500 residents who supported the group’s opposition to the freeway, aiming instead to conserve the valley as native bushland. (53 East Yarra News, 17 July 1973). Donvale resident and naturalist Cecily Falkingham was writing monthly articles for a local newspaper in the late 1980s and early 156????

1990s: I was writing natural history articles for the Nunawading Gazette. At that time the freeway issue was becoming much more topical. It was approaching us at a great rate of knots - it was going to happen. We had to face the fact that the freeway would be going through the Mullum Mullum Valley. The Mullum Mullum had been desecrated to a certain extent with some of the timber going out in the late 1800s for housing and for fencing. But on the whole, the Mullum Mullum looks the same as when the Wurundjeri last walked freely through it a couple of hundred years ago. It’s actually called gorge country, it is so high. In various areas you can stand on a cliff and way, way down, see the trickle of the Mullum Mullum running through gorge country, which is magnificent. In autumn, there’s a wisp of mist that curls like a ribbon all through this valley.' The Hillcrest Forest-way is 25 hectares of bushland that is one small, unique part of the Mullum Mullum Valley. Knowing that it would be very difficult to defend a part of the valley infested with exotic species, residents organised as The Hillcrest Association worked hard to restore this degraded road reserve area to a bush environment. Residents had formed the Hillcrest Association in 1955 to pursue issues such as the provision of parks, play equipment, public telephones and road works. The race against the freeway prompted the Association to divert a lot of time and energy into restoring and managing this special piece of bushland: 'We actually worked every month for about fifteen years on the freeway reservation, knowing that we could lose the lot. People thought we were absolutely mad. 'You're weeding on a freeway reservation.' But we said, 'One day it may be saved'.' Funding the work, which required the purchase of plants, tools and weed spray, proved challenging. The Association found it difficult to convince Council to contribute much money because it was Country Roads Board (later VicRoads) land. 'Because we didn't accept that, we decided to go to Greening Australia and other organisations for funding. It could be anything from $1,700 to maybe as little as $500. The money never covered any of our time. In fact, we used all our own tools mostly, which means wear and tear. Tools get lost in the bush so you'd have to go out and replace them at your own expense.' (54 Responsibility for metropolitan roads was transferred from the Board of Works to the Country Roads Board in 1974)

In the early 1990s the Kennett Government and VicRoads announced that the proposed Eastern Freeway extension was finally to be built. Many people in Melbourne’s outer eastern suburbs welcomed this news, including the City of Doncaster and Templestowe:

Geographically, this City lies in a main truck route. From statistics gathered by Council, out of 80,000 vehicles per day travelling on Doncaster Road, approximately 8,000 carry freight. These freight-carrying vehicles cross the city in the major part of the day. ... The stop/start congestion of freight traffic in Doncaster Road is totally unacceptable for the ratepayers and the economic viability of manufacturing industry. The proposed construction of the Eastern Freeway Extension will undoubtedly alleviate our road congestion problem and thereby improve the overall distribution costs of goods and services across the State. (55 City of Doncaster and Templestowe, ‘1991 - the city today’, p. 17)

Neil Harrington, a regular commuter, remembers what it was like: Trior to the extension of the Eastern Freeway to Springvale Road, the main artery to the city for Manningham residents was Doncaster Road. 'Artery' is too flattering a term to describe a road that comprised only one to two lanes each way and still had some unmade shoulders. Peak-hour traffic along this stretch at its best was testing, and at its worst, tortuous! From the junction on Old Warrandyte Road where Mitcham Road yielded its responsibilities to Doncaster Road, the journey was a series of intersections, pedestrian crossings and shopping strips. There were inevitably long delays at Springvale, Blackburn and Wetherby roads, build- ing to a peak at Tram and Elgar roads. A factor contributing to the traffic volume was that res- idents of the growing outer eastern suburbs often used Doncaster Road as an alternative to Canterbury Road and Maroondah Highway, both of which were also frequently choked.' (56 Neil Harrington, questionnaire, 21 July 2001). The Eastern Arterial extension was to be constructed to Springvale Road. The Council believed this would provide a great opportunity to enhance the streetscape of Doncaster Road, whose function would then be to perform the role of a local arterial road. The Council planned to creconfigure' Doncaster Road to a more acceptable roadscape and pedestrian environment'. (57 City of Doncaster and Templestowe, ‘Designs and directions - our city plan’, 1993, p. 9). But for some residents who lived beside the section of the Mullum Mullum Valley that was eventually going to be covered by an eight-lane freeway, it would mean unwanted consequences. Their major concern was that the full extension works would eventually oblit- erate bushland in the valley’s middle reaches and sever a vital urban wildlife corridor forever. (58 Geoffrey Heard, ‘Mullum Mullum Creek - it’s crunch time; a 30-year battle for an urban wilderness comes to a head’, in Environment Victoria Inc. News, Issue 146, March 1998, p. 3). The Mullum Mullum Creek rises from a spring in Croydon and flows 21 kilometres down through several suburbs to the Yarra River at Tikalara Park, Templestowe. At Mullum Mullum Creek you can be standing just a hundred metres away from a normal suburban streetscape and feel that you're in a genuine wilderness.' (59 Felicity Lang, quoted by Geoffrey Heard, ‘Mullum Mullum Creek - it’s crunch time; a 30-year battle for an urban wilderness comes to a head’, in Environment Victoria Inc. News, Issue 146, March 1998,, p. 3)

A valley worth saving

In 1996 the work of the Hillcrest Association had gained sponsorship from the Australian Nature Conservancy Group and the Association won the Landcare Award for the whole of Victoria: 'When the judges came down to Hillcrest to have a look at the Forest-way, they walked with me and I showed them the wetland instigated by the Hillcrest Association that Greening Australia had created with support from Melbourne Parks and Waterways and Manningham Council.' The wetland had been a denuded area where an open drain had flowed into the bushland: 'It created this putrid, horrible area. The frogs couldn't survive. It was polluted, the trees were dying, the blackberries were becoming the prevalent weed covering everything and ivy scrambled everywhere.' The Hillcrest Association volunteers cleaned the wetland and when the Australian Nature Conservancy Group who were judging the Landcare Award inspected it, 'there were birds singing everywhere, there were waterfowl on the lake, there was a white-faced heron sitting in a tree above it, the frogs were croaking, and an echidna ambled across the track. I showed them photos of what it was like before and the judge laughingly said to me, 'Did you put the echidna there for me or did that really happen?'

Although the residents knew what flora and fauna might be lost to the Valley, not many people outside the immediate vicinity even knew the bushland was there. Another component of the fight, therefore, was the spreading of information as widely as possible: £Once we became aware that the Kennett Government was going to build the freeway, we had to think of ways of communicating to local people that they had an asset that was worth fighting for. How could we possibly inspire people to fight for something they might not have seen?5 In order to raise community awareness, a committee - in consultation with Friends of the Mullum Mullum, the Hillcrest Association and other conservation groups - organised a fes- tival: 'That was the first step - educate, inform, let the people know that its there. Then agi- tate through the various councils - Maroondah, Whitehorse and Manningham - who were the managing authorities who owned sections of the Mullum Mullum and were known to be directly affected by losing the bushland.5

Locals also studied and prepared alternative proposals that would lessen the impact of the freeway on the bush environment: 'We realised the stakes were high. We realised we were going to lose an awful lot. The Eastern Freeway Tunnel Group formed and a group of about twelve men and women worked very hard for about two years to present tunnelling options.5 A hurdle, however, was evident mistrust of tunnelling technologies that were still relatively unfamiliar in Australia. The group ran education nights that helped to calm the fears of some who opposed the idea of a tunnel and inspired others to make submissions of their own to the government: 'The Eastern Freeway Tunnel Group presented four options to the government. Option 3 would have saved the whole valley.5 The Bracks Government considered the Eastern Freeway Tunnel Groups recommendations and in spite of whatever reticence the community felt towards an underground section of freeway, in October 2000, chose the Groups Option 2, incorporating a short tunnel of 1.5 kilometres. As a result the Hillcrest Forest-way has been saved. Drilling commenced in January 2001 on the freeway tunnel, which is to be located underneath houses and the Mullum Mullum Creek: 'That's the most wonderful thing about it. We stopped a freeway going through a valley - but unfortunately not the whole valley - the freeway will go through about half of it, but we set a precedent for other people who live near beautiful patches of bushland or people who live near valleys.'

The decision nevertheless disappointed Falkingham: 'We lose half a kilometre of bush- land; half a kilometre of bushland in one direction and I don't know how many hundred metres in the other, so you'd be looking at an area almost as big as Antonio Park, Mitcham, completely wiped out. Thousands of trees, thousands of animals, and I say thousands and I'm not exaggerating because I'm including the invertebrates - if you include all the invertebrates, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds - thousands of animals is not an exaggeration. There would be dozens and dozens of sugar gliders, echidnas, brush-tail possums and ring-tail possums that will die because of loss of food and shelter, and diminished or destroyed territory. There will be koala habitat that will be lost. I'm not suggesting that when the machines come in the koalas will actually come out of the trees, but there will be unseen animals inside those habitat trees that will die. There will be fish that will die and maybe platy- pus that will die.' But when Falkingham considers that ten years ago she thought the whole lot was going to be bulldozed, she appreciates the concessions that they have gained: 'I mean you can't help but feel overjoyed. The Labor Government has given us half the freeway. So we lose half the animals instead of all the animals. Option 3, with the proposed 2.6 kilometre tunnel, would have left the corridor almost intact. It’s a fairly bitter victory, really. The week leading to the decision I could barely walk there without breaking down and most of us felt that way. You would go down there and you would be struggling to keep control because we'd fought so long and we were so exhausted and emotionally we couldn't cope, walking there was so distressing. You'd see the animals in that environment and you'd be looking at them knowing that they were going to die. After the decision to save it, I went down there next morning very early, just after dawn. I stood beside the creek and wept for joy. A man came along with a dog and walked down. I brushed away my tears very quickly and stood there and tried to get control of myself. And the man (I'd never met him before) said, 'I came down here today because I know this is going to be saved and I feel like I can walk here without breaking down'. It was one of the most moving moments of my life to think that he'd come down there for that reason too. That he felt he could walk there and say, 'This has all been saved'.' (60 Cecily Falkingham, interview, 31 January 2001)

The art of living amongst trees

Upon arriving in Melbourne from London in 1951, a German-born sculptor, who had stud- ied in Europe, viewed the flat landscape: CI remember one night ... standing at the corner of Bourke and Swanston Street and everything was flat. I found it quite depressing. I don't look back - I mean, even then, my attitude was - I don't want to go back - but I always said, all Australia at the time appeared to me as a can of flat beer.' The bland topography of Melbourne created, in artist Inge King, a desire to escape to a place of scenic beauty. Inge had come to Australia with her husband, who was born in Melbourne. Grahame King is known for his major contribution to improvements in modern Australian printmaking, and he is recognised as a significant painter and lithographer. Back in 1951 the couple lived in a furnished room in the suburbs of Melbourne and they shared a little studio in Bourke Street, but Grahame wanted to enjoy bush environs: Tm a local Melburnian. I was in England after the war and I married Inge there and we decided to come back to Australia, which I was very happy to do and Inge was prepared to try. We had spent all our money in Europe so we had virtually nothing. I could earn my living as a designer and, of course, I'm mainly concerned with the study of art, as well. My art history had been Australian landscape, which I loved, and we wanted to try and find some way of enjoying that plus the fact that we were tied to the city to earn a living.' As well as Grahame’s work in design, Inge made silver jewellery in the Bourke Street studio to help make ends meet: 'I mainly made silver jewellery. I had some training from Europe and then I went and did some study in the Metalsmith Department at RMIT. They didn't have a Jewellery Department then but it showed me how to use the equip- ment and so on.' Desirous to move to a house of their own but without much money, Inge and Grahame King wanted land that was reasonably priced, close to the city, and which boast- ed some natural beauty. It was then that their friend, Max Newton, introduced them to his new property in Warrandyte. 'I met one of my friends in the first few months we were back here and he had just purchased a block in Warrandyte, so he drove us out here - we didn't have a car in those days. I knew Warrandyte slightly but not very well and it looked very good and Inge liked the idea. I tried to persuade her that we should look around other suburbs and places, but 'No', she said, 'lets try this'.' Warrandyte was the first place Inge had seen with a view to buying land and building and she decided straight away. The natural beauty of the bush was evident, she and Grahame already had friends in the area, and Warrandyte felt to Inge as if it could be home.

Suburban pioneering in a busy life took its toll on Inge Kings output of sculptures for the first ten years. She had to manage a young family in an unfinished house, on a property with no electricity service and no road, while making jewellery to boost the family finances, and in addition she faced the artistic challenges of a confronting new Australian environment: 'I found the change so great that I hardly did any work for the first ten years. I felt I had to find my way.' Two decisive factors prompted Inge King to find her sculptors voice: one was the inspiration of a new medium. In 1959 the Kings' neighbour, Herb Henke, who was a top engineer craftsman', taught them to weld and it provided a catalyst for Inge to find expression in the medium of steel: £I got inspired - through my visit to America, actually - to use steel. Our neighbour made some arc welders and he actually taught us both welding on a job where Grahame was employed as an architect.' Most of Inge King’s work from then on was done in steel: £I like to do large sculptures. I like to see my sculptures in the landscape. But the Australian landscape is not an easy landscape to conquer. It’s an untidy landscape, it’s rough. I paint my sculptures; in those days, I painted my sculptures black. Those simple black shapes were in great contrast to that landscape because it’s a very powerful landscape. It’s not a mat- ter just of size, but it’s a matter of the power of the work that it can stand out, or stand up, against the landscape.' The other factor that made King begin sculpting again in earnest was her environment - her Warrandyte surroundings: £It was really partly the landscape at Warrandyte where we look out that inspired the works I did later on, and it has done so ever since'. For Grahame King, £it’s the fact of living amongst trees. There were the Australian-type artists who thought art was a matter of painting gum trees. Since Europe and other studies, I no longer paint gum trees; but I find it perpetually satisfying just to look across the hills and the big trees and the river. It’s a rich feeling that one can't define very clearly.' (61 Inge and Grahame King, interview, 6 March 2001)

Source: Barbara Pertzel & Fiona Walters, Manningham: from country to city, Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2001. Manningham Council granted permission to reproduce the book contents in full on this website in May2023. The book is no longer available for sale, but hard copies of the original are available for viewing at DTHS Museum as well as Manningham library and many other libraries.

No comments:

Post a Comment